Miss Representations: No Room for Blackness or Feminism on Mad Men’s Sets

Whitten Overby / Cornell University

As some have noted but few have probed, Mad Men, Matthew Weiner’s critically-lauded, recently departed, dolled up soap opera about white masculine decline and white female ascent in the 1960s New York ad agency Sterling Cooper, has a racial and feminist representation problem. The Women’s Liberation, Civil Rights and Black Power movements were fermenting during the 1960 to 1970 time period covered by the show, but, save for two peripheral African-American female secretarial figures, Mad Men problematically asserts the dominance of the white, straight, affluent male gaze within both its historical period and its viewing present. While this male gaze, especially as enacted by the show’s anti-hero protagonist, Don Draper, dominates the spaces of the agency’s white and black female workers, this series of three columns tackles a broad representational issue: first, against common claims that Mad Men is feminist, I argue that its corporate modernist sets reveal the show to be a perpetuator of white patriarchal domination of the American workplace and, secondly, how Mad Men’s refusal to explore how spaces of disenfranchised and segregated black characters echoes broader discriminatory practices within architectural and televisual creative cultures. Mad Men’s modernist office sets facilitate the show’s systemic perpetuation of the American masculinist creative culture as well as the racial and gendered divides between black and white, male and female American citizens.

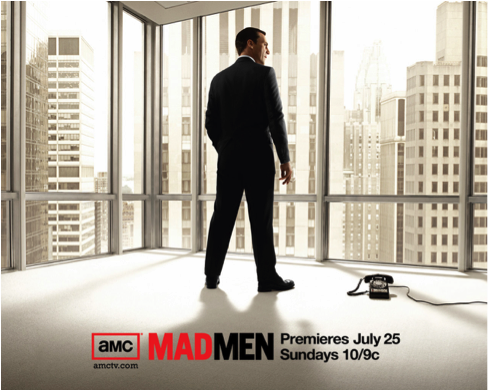

As I see every year in the designs of my first year architecture students, architectural history, theory, and design cultures continue to be dominated by the modernist aesthetic found in the Sterling Cooper office sets. Mad Men’s season four promotional poster expresses the overt whiteness and maleness of this aesthetic, with Don standing in a crisp, empty, ready-to-be-dominated corner office staring out onto a sea of other skyscrapers. In design but also American popular culture, the skyscraper is, to be blunt, conceived to be symbolic of a giant penis and thus bespeaks the masculine domination of space. In the immediate postwar period, the modernist Manhattan skyscraper represents corporate restructuring and the concomitant solidification of binary American gender politics, with women only occupying low-level positions or, worse yet and as Betty Friedan decried in 1963, The Organization Man’s homemaking other.[1]

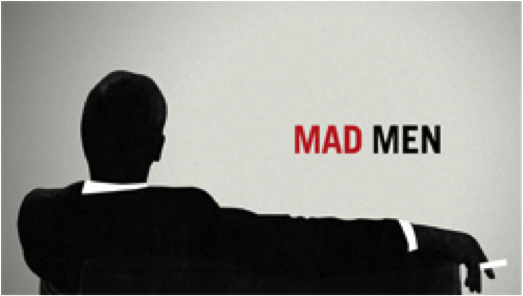

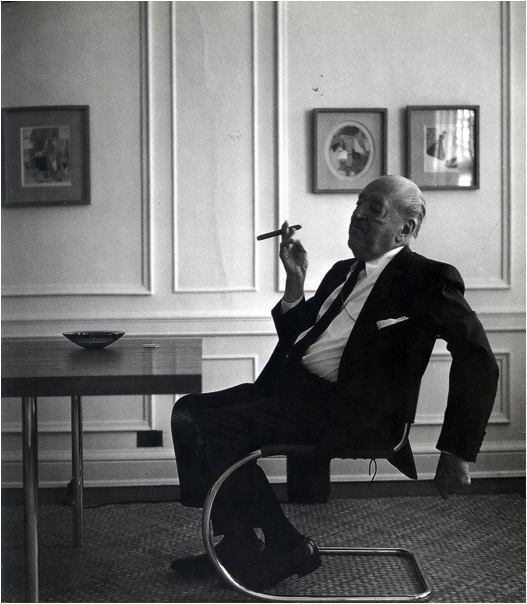

Mies van der Rohe and his Seagram Building are the premiere postwar articulation of this skyscraper, PR-friendly patriarchal design culture. In its 2014 Venice Biennale show Elements, the Office for Metropolitan Architecture called Seagram a “monument,” and especially noted its use of the new partition wall to enable its interior spatial flexibility. The offices of Mad Men’s ad agency in seasons four through seven have partition walls and reflect not only the rapid growth of corporate America but also the spatial politics by which its male partners dictate the contents and borders of their office’s partition walls. Moreover, Mies’ most famous dictum, “less is more,” echoes the hard, universalizing, catchphrase-centered culture of midcentury masculine advertising. But the most striking correlation between Mies and Mad Men comes in the opening credit’s final shot. The animated ad mad is pictured from behind, smoking a cigarette, while Mies is usually photographed smoking a cigar. Both are upper middle class, professionalized white males iconized by the leisurely intake of tobacco in private offices while women toil away in undivided, exposed office spaces. If, as Marxist spatial theorist Henri Lefebvre claims, Mies is the leading architect of “a space characteristic of capitalism,” then Don Draper and other ad men are those spaces’ premier tenants.[2]

It is thus within the public and private spaces of the skyscraper office that Mad Men’s white, straight males make the final creative decisions that dictate their agency’s future. Echoing this fictional spatial narrative, the creative culture of twentieth and twenty-first century architecture has been almost entirely white and male, in part explaining how that demographics’ most popular corporate architectural style continues to dominate design culture—like, normative, homogenous bodies producing like, normative, homogenous spaces. Corporate modernism’s history is one long Great Man Theory and, despite Spike Lee’s 1991 film Jungle Fever, which has a black male architect protagonist, in 2007 only 1% of registered architects were black and, in 2004, only 20% were women. Architecture school enrollment statistics reported in 2012 reveal a slightly different story, with only 5% black but 43% female. [3] The 2014 employment numbers at ad agencies are even more depressing: only 5% of employees were black, while only 4% of women were creative directors.

Modernism first emerged in Europe in the early twentieth century but made its American splash with MoMA’s 1932 International Style architecture exhibition. The show’s curators, Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock, selected primarily domestic architectures that represented a terse, clean, and simple emphasis on a formalist geometric purity—rectilinearity—executed, in part, through open floor plans and windows with streaming sunlight. Johnson is perhaps the most important figure in twentieth-century American architecture and his public persona demonstrates the convergence of the three of the most significant midcentury mass media (television, advertising, and modernist architecture): as an openly gay man, he was an interloper in a heteronormative straight professional culture; as an architect, he collaborated with Mies on the Seagram Building, for which he designed some of its key interiors; as a curator at MoMA, in 1947 he put on the first Mies van der Rohe solo exhibition anywhere and, in 1988, he dubbed a group of “deconstructivist architects” the stylistic innovators succeeding his International Style modernists; and, as architectural theorist Beatriz Colomina argues, Johnson, despite his avowed rejection of television and other mass visual media because “[only] architecture is how you enclose space,” [4] was “like a TV personality…a TV program, a reality TV show that ran longer than anyone could have imagined.” [5] Johnson was also like an ad man for elite architectural taste in America, coronating successive waves of architects like television producers created stars and ad men created verbal and visual slogans. Postwar American architecture was thus largely the product of a white, male advertising campaign that only once over its eighty-year span included women in its canon.

Spearheaded by Johnson, who turned high architectural culture into a mass consumable commodity expounded in clear, simple, marketable characteristics, the integration of television, advertising , and corporate modernism constitute what I consider to be the postwar period’s actual military-industrial complex. All three ‘creative’ professions were giant corporate ventures by Mad Men’s 1960 start, and they all— ironically, given their overlapping production of solely mass media—relied upon the elite patriarchal associations of architectural modernism’s history. While introduced in 1932, modernism did not become the dominant architectural style in America until the immediate postwar period when, as American architect Kenneth Reid wrote in 1942, the national design culture was looking for “leaders of undeniable maleness who are bold and forthright and stoutly aggressive” to articulate the booming corporate interests represented by Madison Avenue ad agencies. [6]

It was not just ad agencies like Sterling Cooper that used corporate modernism as tools of advertising and patriarchal domination. The Big Three and their local affiliates built new modernist television production facilities and corporate headquarters in New York and Los Angeles, and, like advertising, their corporate hierarchy and creative output was generated by almost exclusively white men producing content for audiences with a white, heterosexual, middle class demographic. Television historian Lynn Spigel chronicles the design through the opening of CBS’s first 1953 Los Angeles production facility Television City, which she claims “communicates the experience of television as a design concept.” [7] By using the elite design aesthetic of modernism as a public branding technique, television made an early argument that its mass mediated cultural productions were like an art form. CBS’s 1964 Midtown Manhattan corporate headquarters, a skyscraper located adjacent to Rockefeller Center, creates a far stronger correlation between Mad Men and corporate modernism, illustrating how by the mid-1960s the large, multitenant office building, primarily funded by a named corporation, became the definitively white, male emblem of creative professional work. Despite the multiple transitions in the production and distribution of new television content—the recent insurgence of especially black female televisual representation, a move that would seem to necessitate a reconsideration of corporate televisual modernism—the television industry continues to house itself in modernist corporate environments with similar managerial and creative identity-based inequalities. Mad Men’s corporate modernism thus doesn’t just tell the history of 1960s advertising; it provides a look into contemporary corporate creative culture.

As many have pointed out, and unlike much of what historian Merrill Schleier has called “skyscraper cinema,” Mad Men almost never shows the exterior of the office buildings in which its characters spend the majority of their time. [8] Instead, the camera meditates mainly on Don alone and with colleagues in his office. This focus on white straight masculine interiority corresponds to the dynamics of gender and sexuality as embodied by the midcentury skyscraper. The authoritative lines of corporate modernism are matched by the solidification of the male patriarchal domination of workspace—their position in corner offices with curtain-walled windows—and the ancillary roles, and interior, window-less spaces that women were relegated to. Indeed, for the majority of Mad Men’s run, only one woman, Don’s protégé Peggy Olson, receives her own windowed office, the rest of the female secretarial pool confined to fully open then partitioned interiors to be easily observed by their male bosses.

I’d like to make an admission: like many of Mad Men’s commentators, I spent my first run viewing of the show considering it something of a feminist masterpiece. I even, as shown below, posted a paean to its female protagonist Peggy Olson on my Facebook page. The bitter irony of making semi-public my misinterpretation of a sudsy but perhaps too championed show now resounds, as I complete my second full viewing of it, as my attempt to rationalize my pleasured enjoyment of an aesthetically and ideologically conservative soap opera. It would seem that, in having sat through and partially taught architectural history survey courses for eight years and counting, I’d accustomed myself to the very corporate architectural modernism, and its violent symbolic assault on female and black persons, that I encourage my students to critique and disengage from. The most telling part of my Facebook post is, however, the sole comment, left by a former yoga teacher, that Peggy’s “becoming Don.” I’d like to propose that, in addition to slavishly recreating corporate America’s patriarchal heyday, Mad Men recreates the patriarchal politics of the 1960s iterations of its primary generic category, the soap opera. Published in 1970, the same year as Mad Men’s conclusion, the intersectional feminist anthology Sisterhood is Powerful contains an essay that critiques the architecture-advertising-television complex illustrated by Mad Men’s narrative spatial emplacements. In her essay “Media Images I: Madison Avenue Brainwashing—The Facts,” Alice Embree claims that television is the primary nationally disseminated media controlled by the ad agencies of Madison Avenue. Significantly, Embree cites the soap opera as the televisual programming genre that most clearly exhibits and bolsters “the image of male-dominated women,” and she especially singles out the depiction of the white, middle class, corporate professional man (that’s you, Don Draper) as the corporeal and spatial soap opera figure making this assertion. [9]

Over the course of the show, as Peggy Olson ascends the corporate ladder, she is, as my yoga teacher’s comment suggests, increasingly masculinized as an embodiment of liberal individualism. Popular and academic commentators on the show have called it “TV’s most feminist show,” but, in reality, it’s a show about men dominating women and women acquiescing to its male characters’ demands in order to achieve personal and/or professional success. Perhaps Peggy’s navigation of corporate modernism is a second wave feminist tale of liberal individualism, but she’s largely unhappy, unliberated, and depressed over the show’s run. Indeed, liberal individualist ideology was promoted by early, white, middle class second wave feminists, and this movement’s contrast with the collective working culture of feminized office culture—and black feminism—renders it a patriarchal American spatial myth: a pursuit of an office of one’s own that was considered out of reach by and for most women. [10]

Indeed, all accounts of white and black authors who write about working in corporate America in the 1970 intersectional feminist anthology Sisterhood is Powerful state that, based upon their lived experiences, women never rose above the level of glorified secretary and never moved from open, interior, and public workspaces into private, windowed offices.[11] It would thus seem that Peggy’s corporate spatial ascent is an unlikely fictional conceit provided by white male apologists-cum-television creative to furnish a point of identification for contemporary female viewers and to lull male viewers into thinking the show was advancing a progressive (historical) agenda. Moreover, the aesthetics of Peggy’s office—warm wood paneling in stark contrast to Don’s clean whites—directly echo those of Seagram’s initial luxurious wood modernism, and her feminine domination of such a space corresponds to her narrative assumption of masculinist, unwavering, unsympathetic assertiveness. As importantly, Peggy’s refusal to collaborate with or advocate for her female co-workers demonstrates her ideological assumption of patriarchal corporate spatial divides. Audre Lorde’s 1979 black lesbian feminist manifesto “The Master’s Tools will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” should ring in the ears of Mad Men viewers. Not only does Peggy use patriarchal professional and social tools to enable her spatial ascent, but she also doesn’t embrace Lorde’s claim that “for women, the need and desire to nurture each other is not pathological but redemptive, and it is within that knowledge that our real power is rediscovered.”[12]

In the series’ second episode, “Ladies’ Room,” Peggy is met with iciness by her new coworkers, initiating her corporate experience with inter-female hostility in Sterling Cooper’s only fully female space. But Peggy doesn’t have a desire to change this flawed social-political system. Instead, she engages in a largely competitive corporate jockeying, a political battle, with Sterling Cooper’s other ascendant white female employee, Joan Holloway. They’re most frequently shown riding the elevator up and down to the Sterling Cooper offices, and, in their tense final ride, Joan informs Peggy, after being sexually harassed by men at a competing firm, “I want to burn this place down.” Peggy doesn’t join Joan in her attempt to overthrow corporate sexual discrimination. Instead, she gets off the elevator and goes to her office, concluding the series by integrating herself, more than ever, into the male-dominated spaces of corporate America.

Further defying Lorde’s 1979 call to arms, Peggy several times displaces black female coworkers by making racist assumptions about black working class women who belong to the same spatially exposed secretarial pool she starts the series within. First, after discovering Don’s new secretary Dawn sleeping in his office and inviting Dawn to her apartment, Peggy thinks Dawn has stolen from her and Dawn, depicted in narrative shorthand as an abject, spatially unmoored black woman, leaves the supposed white feminist domestic sphere feeling the opposite of sisterhood and spatial togetherness. In effect, Peggy stereotypes Dawn as a poor, black thief, a domestic interloper, demonstrating how stereotypes are “a fantasy, a projection onto the Other that makes them less threatening.” [13] Instead of truly opening her space to intersectionality, making the emotionally risky decision to trust a black woman and thus truly making her home a place of feminist togetherness, Peggy makes the comfortable, “less threatening” social and political decision to racially police her personal space. Second, Peggy falsely presumes that flowers sent to her black secretary Shirley were intended for her, as if the Sterling Cooper offices, in their resounding modernist whiteness, has no space for black women to be given any attention. (This incident serves as a partial excuse for Peggy to request Shirley be re-assigned, making it overt that black women’s place within the Sterling Cooper office is subject to white overseers’ whims.) My emphasis on ‘modernist whiteness’ is intentional: Madison Avenue is literally, spatially. Moreover, when the historical spatial evolution of this advertising world is turned into a narrative with equally historical soap opera conventions, Mad Men crystallizes into a show conceived of, executed by, and representative of male patriarchy’s domination of American corporate space.

Discussion to be continued in Flow 22.04.

Image Credits:

1. The Mad Men season 4 promotional poster

2. Final shot of the Mad Men opening credits (author’s screen grab)

3. Architect Mies van der Rohe smoking a cigar

4. Sea of skyscrapers (author’s screen grab)

5. Facebook post (author’s screen grab)

6. Peggy Olson in her office (author’s screen grab)

7. Peggy Olson in “Ladies’ Room” (author’s screen grab)

8. Peggy Olson and Joan Holloway ride the elevator up to Sterling Cooper’s offices (author’s screen grab)

9. “On the Next Mad Men“

Please feel free to comment.

- See Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique (New York: W.W. Norton, 1963) and William H. Whyte, The Organization Man (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1956). [↩]

- Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, translated by Donald Nicholslon-Smith (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1991), 126. [↩]

- See (1) Craig Wilkins, The Aesthetics of Equity: Notes on Race, Space, Architecture, and Music (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007) and (2) Jenna M. McKnight, “Why the Lack of Black Students?,” Architecture Record (November 2012), available online at http://archrecord.construction.com/features/Americas_Best_Architecture_Schools/2012/Architecture-Education-Now/Diversity.asp. [↩]

- This Philip Johnson quote comes from his three part, 1976 Camera Three television interview, which aired on CBS. [↩]

- Beatriz Colomina, Domesticity at War (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007), 191. [↩]

- Quote taken from Andrew Shanken, 194x: Architecture, Planning, and Consumer Culture on the Home Front (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 5. The quote is from Kenneth Reid, “New Beginnings,” Pencil Points 24 (January 1943), 242. [↩]

- Lynn Spigel, TV by Design: Modern Art and the Rise of Network Television (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 128, but see pages 110-143. [↩]

- See Merrill Schleier, Skyscraper Cinema: Architecture and Gender in American Film (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009). [↩]

- Alice Embree, “Media Images I: Madison Avenue Brainwashing—The Facts,” in Sisterhood is Powerful: An Anthology of Writings from the Women’s Liberation Movement, edited by Robin Morgan (New York: Vintage, 1970), pages 175-191. [↩]

- For a discussion of the relationship between the American ideologies of liberal individual (and its 1960s white, middle class, bourgeois feminist associations) and its contrast with collective black feminism, see bell hooks, Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center (Boston: South End Press, 1984), pages 1-15. [↩]

- For a comparative discussion of female workplaces in the Connecticut suburbs and Manhattan in the 1960s, see Judith Ann, “The Secretarial Proletariat,” in Sisterhood is Powerful, pages 86-101. For a discussion of a black female proletariat working in mass media, see Shelia Smith Hobson, “Women and Television,” in Sisterhood is Powerful, pages 70-76. [↩]

- Audre Lorde, “The Master’s Tools will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” in Gender, Space, and Architecture, edited by Iain Borden, Barbara Penner, and Jane Rendell (New York: Routledge, 2000), 54, but see pages 53-55 for the full text. [↩]

- bell hooks, “Representations of Whiteness in the Black Imagination,” in Black Looks: Race and Representation (Boston, MA: South End Press, 1992), 170. [↩]

I wonder if you could comment on modernist skyscraper hotels, like the New York Hilton Midtown (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_York_Hilton_Midtown). Do their function as quasi-domestic spaces problematize the prevailing rhetoric re postwar modernist skyscrapers? Especially since they *seem* to offer women a chance to occupy the same space as men. (Though, aside from Don and Betty’s anniversary in “For Those Who Think Young,” Manhattan hotels in Mad Men seem to be reserved for white men to conduct business and extramarital affairs. Hmmm…)

Excellent column, btw.

Pingback: The Madness of Angeleno Freeways: Auto Mobility, Futurism, and Masculine Desire Whitten Overby / Cornell University – Flow

Peggy Olson is a feminist hero, in neo-liberal terms which champions the individual over the struggles of women in general. As far as the architecture goes, it is a period show, it was showing us how the times were, not how we’d like them to be. What is the point of that? The same goes with its characterizations of women and people of color. There was a lot going on internally with Peggy and Joan as women navigating a very male dominated world that was brought out on the show. Joan having many talents beyond her much admired physical appearance, but being treated always like a glorified secretary and a sex object. Peggy’s talents being described as “like a dog playing a piano”…. Architecture is still a male dominated field, I’ve worked with architects and I have seen how many women are treated in the architectural field. Not often very well. Do you have a suggestion as to what a more woman friendly and people of color friendly architecture would actually look like? It’s one thing to criticize, that’s the easy part. The harder part is offering a solution. A period piece if it is good should show things as they were. I think Mad Men comes pretty close.