Punk, Disco, Porn—The Deuce ’77—Part 3

Matthew Tchepikova-Treon / The University of Minnesota

Porn. “What am I watching? What the fuck are we doing here? Come on, so now we’re making art?” Rip-and-run porn producer Harvey Wasserman, in the lap of a churning 16mm Steenbeck, examines the climax sequence from Candy’s latest film: close-up images of a woman and two men with cutaways to a ceiling fan, wild life, juiced fruit, etc. Candy responds: “It’s cut the way an orgasm feels… So some of it’s in her head. Some of it’s real. Some of it’s somewhere in between.” Harvey responds with a string of sardonicisms, applauding the “ethereal Warholian fashion” with which Candy has attempted to visually represent “the female mind for the final stampede to nirvana.” In a way it’s a genuine, if still patronizingly veiled, recognition of aesthetic ingenuity. Nonetheless, Harvey cedes to an industrial imperative—“Keep the focus on the fucking”—that demands phallic fantasy production. Candy responds with a dissatisfied summation: “Porn.”

Aural Pleasure & Acousmatic Women

Concerning sexual penetration, “proof” of orgasm, and conventional filmic displays of female pleasure, this scene practically stages Linda Williams’ well-worn dictum that hard-core pornography “seeks maximum visibility in its representation but encounters the limits of visibility of its particular form.”[1] In mainstream heterosexual porn production, where the industry-standard “money shot” serves as visual confirmation of male satisfaction, conversely, women’s overdubbed voices do the work of sonically signifying orgasmic bliss, becoming “aural fetishes of the female pleasure we cannot see,”[2] while also further revealing “the inability of a phallic visual economy to imagine female pleasure as anything but insufficiency or excess.”[3] Additionally, Eithne Johnson argues that, “at the site of the female body,” this disembodied sonic excess is “displaced onto the ‘body’ of the film, where it functions as surplus semiotic material.”[4] As an immediate example, listen to the overdubbed vocal work of a female performer added by Candy after recutting the aforementioned climax sequence and how The Deuce crosscuts Candy examining her film with a sex scene of its own:

Crosscutting Overdubbed Sounds from Matthew Tchepikova-Treon on Vimeo.

We hear the electric hum of Candy’s 16mm projector running film, its monophonic speaker emitting the thin sound of a woman moaning, her voice unmoored from any image, from any sense of corporeal verisimilitude,[6] then the far more convincing sex sounds of Abby and Vincent in bed with heavy breathing and Abby’s own voice coming out in arhythmic fits of pleasure. Then back, the overdubbed voice in Candy’s film becoming almost laughable while also sounding more like ecstatic whimpering or even cries of pain.[7] Comparatively, Abby and Vincent finish, yet with a notable lack of spectacularized pomp or circumstance, but then Abby intones a deep “mmhmmm” between breaths, suggesting satisfaction. The film likewise finishes and we hear the sound of leader tape slapping the take-up reel as it spins out, clicking rhythmically with every pass as Candy lights a cigarette—we’ve just seen Vincent reach for his—then exhales. Notably, her own satisfaction seems uncertain.

Invoking a lineage of women filmmakers from Doris Wishman to Candida Royalle,[8] in season two of The Deuce, Candy works to make alternative filmic representations of sex available.[9] Nevertheless, as her opening exchange with Harvey attests, we are reminded again and again that she finds herself doing so within a restrictive audiovisual regime of erotic cultural production, a regime shot through with regulatory powers that extend far beyond porn.

Within a simultaneously emergent audio culture outside the production of moving-image pornography, the female voice as a fetishized sonic object flows between myriad forms of media while repeatedly servicing the same phallic order of hard-core porn’s visual economy. In the broader context of Seventies sexology, Jacob Smith demonstrates how erotic LPs marketed as “instructional” records routinely featured women vocalizing orgasms in order to “sonically index” particular sex practices while also arousing listeners.[10] Likewise, John Corbett and Terri Kapsalis track technologically mediated acousmatic women through a multitude of pop songs that further work to reproduce these “aural codes of sexuality.”[11] “Do it to me again and again,” Donna Summer moans on her disco classic “Love to Love You, Baby.” In Moroder’s extended mix, she performs a “marathon of 22 orgasms”—a writer at Time magazine apparently counted them back in 1975.

As evidenced here, I am inclined to follow Eric Schaefer’s argument that, throughout the late 1960s and 1970s, “a rapidly and radically sexualized media accounts for what we now think of as the sexual revolution.”[12] However, this media revolution was likewise accompanied by a censorious scientism that, as if attempting to re-suture the audible excess of female pleasure back onto women’s bodies, worked to reinforce staid representations of ‘tasteful’ sexuality.

Exposed Legs & the Legibility of Excess

In my previous column on The Deuce and disco, I gestured toward the fact that, throughout the 1970s, urban sound, acoustic research, and the politics of cultural production converged within a revised discourse of noise pollution where familiar sexist visual tropes of female promiscuity emerged in politically motivated projects aimed at ‘cleaning up’ U.S. cities in the name of sexual sanitization. Recall the acoustician who cited a New York discotheque as the loudest source of noise in the city, writing that “the miracle of electronics allowed performers to create a sound level as astonishingly elevated as the dancers’ hemlines.” And while analogizing short skirts and noise during this time was by no means exceptional, as with The Deuce’s second season, we can move from New York to LA to find a most extreme instance.

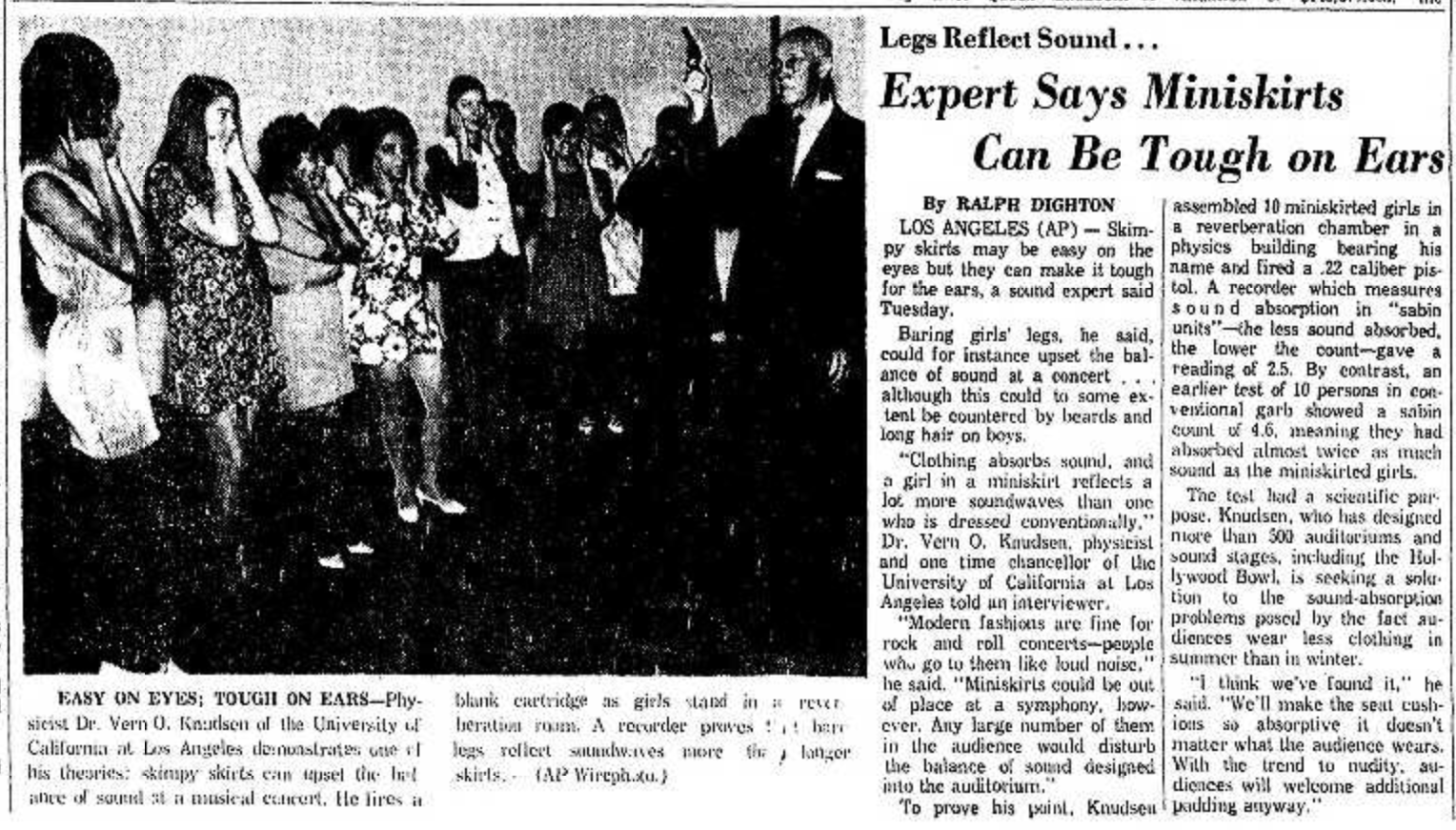

“Dr. Knudsen fired a pistol in a room with 10 miniskirted girls,” reads an account of this famed acoustician discharging a blank cartridge in a UCLA physics department’s reverberation chamber along with ten women in short skirts to measure the level of sound reflection off their exposed legs.[13] Using an acoustical unit of measurement for sound absorption, Knudsen recorded a sabine count of 2.5 that he compared to a test conducted back in 1964 with more thoroughly clothed subjects where reverberations from the gunshot had registered 4.6 sabines.[14] In conclusion: Knudsen used his gun to prove (an already well established fact, mind you) that “as skirts go up, sound absorption goes down.” Associated Press science writer Ralph Dighton’s descriptions of the “experiment” received notable traction in trade journals and city newspapers, with headlines ranging from the pedantic, “Acoustical Test Shows Miniskirts Affect Sound,”[15] and the epigrammatic, “Miniskirted Girls Long On Sound,”[16] to the prolix, “Honey, Your Miniskirt Looks Great, But It Sounds Awful,”[17] and the prognostic, “Miniskirts Bound To Be On Way Out.”[18]

While Knudsen’s ostensible concern involved modern methods of concert hall design utilizing sound-absorption coefficients that accounted for heavily clothed audiences—coefficients reportedly threatened by women’s skin—my reason for comparing his “experiment” (and the rhetorical trope of the miniskirt at large) with that of moving-image pornography’s aural fetishization of female pleasure is to highlight a certain epistemological affinity between ways of seeing and ways of hearing where shared vectors of power, difference, and knowledge converge through science, aesthetics, and cultural politics alike. “Modern fashions are fine for rock and roll concerts,” Knudsen claimed, “people who go to them like loud noise.”[19] But for classical music, he suggested “seat cushions so absorptive it doesn’t matter what the audience wears. With the trend to nudity, audiences will welcome additional padding anyway.”[20] Thus, in Knudsen’s spectacularized stunt, exposed legs became both source and synecdoche of unwanted sound when acoustical engineering attempted to take an aurally perceived (and culturally determined) excess and make it visibly legible on women’s bodies.

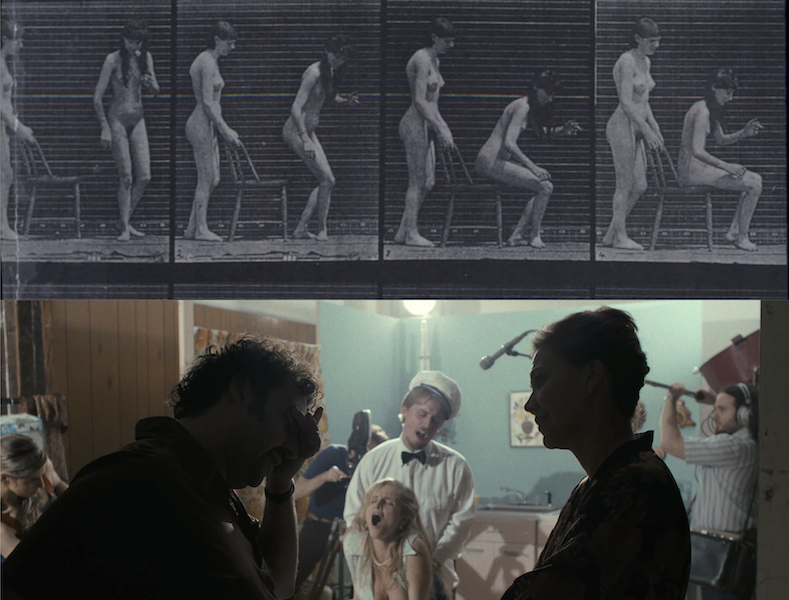

Accordingly, where Linda Williams recognizes in the protocinematic photography of Muybridge a “scientific impulse to record the ‘truth’ of the body”’ that constructed “women as the objects rather than subjects of vision,”[21] by attending to sound as a culturally contested mode of knowledge production concerning human bodies, convergent bodies of knowledge, and the sonic production of social space, we find a similarly motived acoustical discourse where old prurient fears of an unruly eros have been quite literally re-envisioned in sonic terms. And from the porn industry’s frenzy of the audible to an industrious scientism that sought to elide undesirable sounds, in the 1970s, as the tagline for The Deuce Season Two tells us, “pleasure was a business, and business was booming.”

Image Credits:

1. The Deuce Season Two Poster Art (color altered by author).

2. Shots from The Deuce, Season Two, Episode 1, “Our Raison d’Etre” (transferred to GIF format by author).

3. Sound from The Deuce, Season Two, Episode 1, “Our Raison d’Etre” (excerpted as audio by author).

4. Shots from The Deuce, Season Two, Episode 9, “Inside the Pretend” (transferred to GIF format by author).

5. Newspaper clipping from The Joplin Globe, October 29, 1969, front page.

6. Eadweard Muybridge photographs taken from the cover of Linda Williams’ 1999 edition of Hard Core and a still image from The Deuce, Season One, Episode 8, “My Name Is Ruby.”

Please feel free to comment.

- Linda Williams, Hard Core: Power, Pleasure, and the “Frenzy of the Visible” (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), 94. [↩]

- ibid, 123. [↩]

- ibid,109. [↩]

- Eithne Johnson, “Excess and Ecstasy: Constructing Female Pleasure in Porn Movies,” Velvet Light Trap, 1993, 31. [↩]

- For a keen take on “the evolution of prostitution and the birth of large-scale porn production in a medium—on a specific network, even—that’s been criticized for its gratuitous and sometimes violent sexual content,” as well as an interview with season one pilot director, Michelle MacLaren, about the ways she and the show’s production team worked to address this, see: Alison Herman, “How Michelle MacLaren Brought The Deuce to Life,” The Ringer, September 6, 2017. [↩]

- Such an effect often resulted from technical limitations as well as recording techniques that sacrificed spatial realism for a sense of aural presence. [↩]

- For more on this aural slippage between pain and pleasure, see: Clarice Butkis, “Depraved Desire: Sadomasochism, Sexuality and Sound in mid-1970s Cinema,” Earogenous Zones: Sound, Sexuality and Cinema, ed. Bruce Johnson (Sheffield: Equinox) 2010, 66-88. [↩]

- See: Elena Gorfinkel, “Sex and the Materiality of Adult Media,” Feminist Media Histories, Vol. 5 No. 2, Spring 2019: 1-18. [↩]

- Beyond the aesthetic economy of mainstream heterosexual porn production, for a fantastic analysis of the political potential of sound and the voice in gay male pornography, as well as particular techno-erotic affiliations with the phone sex industry during the 1980s, see John Paul Stadler’s recent article “Vocalizing Queer Desire: Phone Sex, Radio Smut, and the AIDS Epidemic,” Feminist Media Histories 5, no. 2 (2019): 181-210. And for more on the phone sex industry, listen to Sexing History’s podcast episode “Sex Over the Phone.” [↩]

- Jacob Smith, “33 1/3 Sexual Revolutions Per Minute,” Sex Scene: Media and the Sexual Revolution, ed. Eric Schaefer (Durham: Duke University Press), 2014, 179-206. [↩]

- John Corbett and Terri Kapsalis, “Aural Sex: The Female Orgasm in Popular Sound,” TDR 40, no. 3 (1996): 102-11. [↩]

- Eric Schaefer, Sex Scene: Media and the Sexual Revolution, 3. [↩]

- Popular Science, October 1969: 20. [↩]

- These details were publicized in the University of California’s University Bulletin, Volume 18, January 12, 1970. [↩]

- ibid. [↩]

- Tucson Daily Citizen, October 30, 1969: 14. [↩]

- The Miami News, October 29, 1969: 2. [↩]

- In this last article, one Clayton Rand of The Jackson Sun foretold of the miniskirt’s imminent falling out of fashion, then claimed, “There are also stock market experts who believe that lengthening skirts usually herald a depressed economy.” He cites no evidence. November 30, 1969: 4. [↩]

- Quoted in “Honey, Your Miniskirt Looks Great, But It Sounds Awful.” [↩]

- There are two unmistakable ironies: First, the unit of measurement used by Knudsen takes its name from physicist Wallace Sabine who, as Emily Thompson’s work shows us, once threw out thousands of measurements while evaluating the duration of residual sound “after determining that the clothing worn by the observer (himself) had a small but measurable effect upon the outcome of his experiments.”Second, as early as 1900, Sabine had developed a quantitative analysis of various absorption powers with precise focus on seat cushions as a remedy to unwanted sound reflection. Knudsen, undoubtedly aware of this, proved nothing. For more on Wallace Sabine, see: Emily Thompson, The Soundscape of Modernity: Architectural Acoustics and the Culture of Listening in America, 1900-1933 (Cambridge: MIT Press), 2002, 36. [↩]

- Linda Williams, Hard Core, 38-45. [↩]

hehe nice thanks.

Pinoy Tambayan is basically exists on two pillars which are ABS_CBS Network and GMA Network. Both the networks are competitors to each other and due to which they are providing the best entertainment to the Filipino people.

I think other website owners should take this web site as an example , very clean and superb user pleasant design.

I found this site is very incredible. Thanks admin for such amazing post.

hahaha Great Work.

Even though I am here for the first time, I am very impressed with your post. Thanks for sharing.

Star Plus Show, Production company, Premiere Date. Kabhi Kabhie Ittefaq Sey,

Cockcrow Pictures Shaika Entertainment Magic Moments Motion Pictures, TBA.