Syndication 203: A Waxy Queer Buildup

Taylor Cole Miller / University of Georgia

This column is part of an ongoing series. The previous installment of this series can be viewed here.

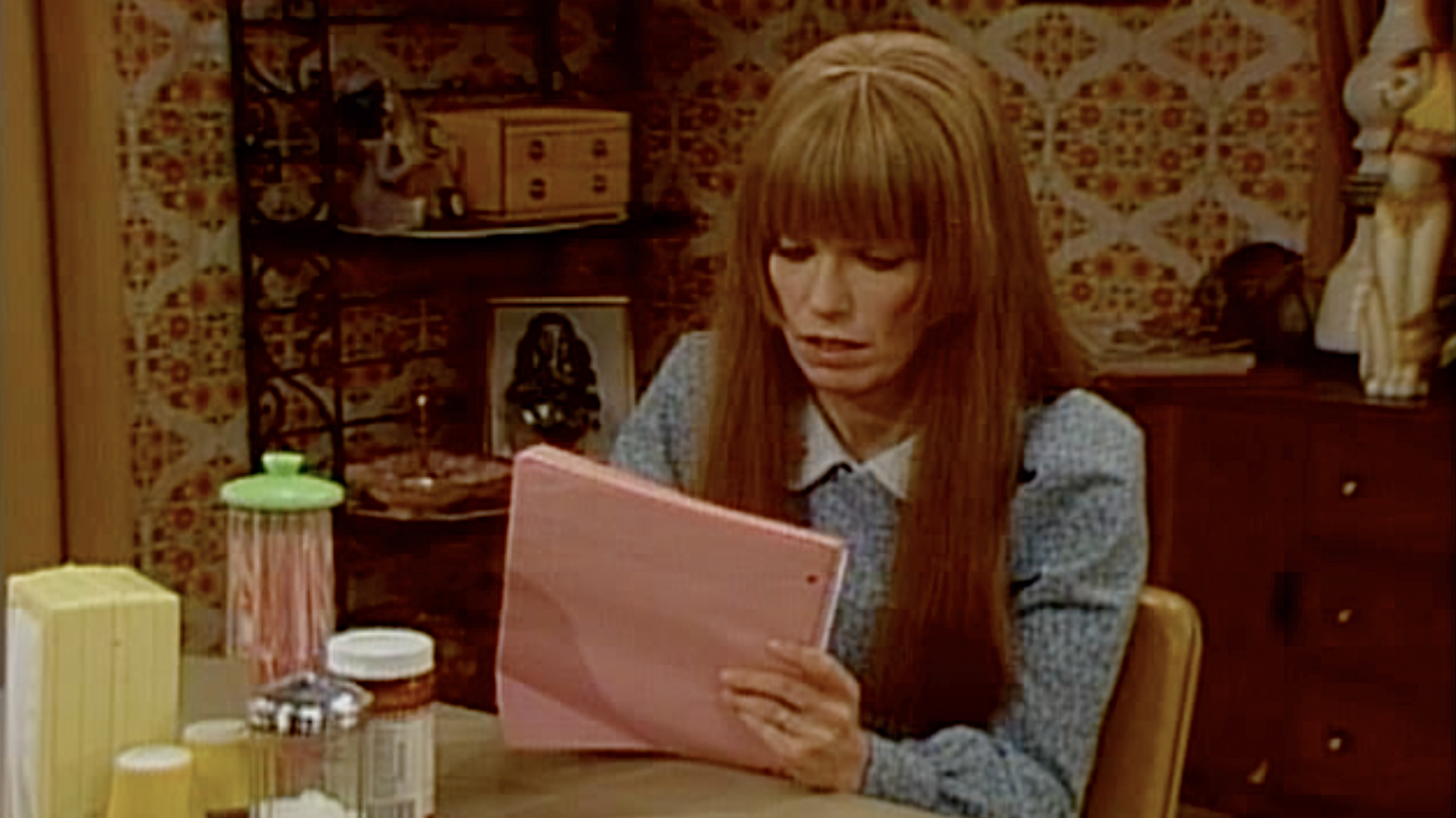

Mary Hartman sits at her kitchen table grasping a notebook of pink paper. She dons her iconic prairie minidress with its Peter Pan collar and optimistic shoulders, but her hair falls unraveled from its signature braids offering hints that something is undone. “Dear Journal: What I’ve been thinking about lately is being bisexual. Bi, as in bicentennial, only, a little dirtier.” Probably the most common refrain conjured for TV historians and journalists about Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman is that the 1976-77 syndicated serial was ahead of its time. But its star Louise Lasser always echoes the same retort: “Mary Hartman wasn’t ahead of its time; it was its time.” And perhaps the show never proves that sentiment better than by inviting us to join her at the kitchen table as she records these thoughts on culture, feminism, and sexuality in the 1970s.[1]

In this installment of my series, I discuss the potential that television syndication has offered queerness over the years through a case study of Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman. Whereas the TV history canon we tend to cling to emphasizes the networks and their practice of least objectionable programming, a turn toward histories of local or first-run syndication exposes a very different picture of television’s past. And while there are plenty of decidedly normative syndie shows, queer sexuality, gender, and genre often epitomized the practice of first-run syndication like in hit daytime talk shows where queer people first spoke for themselves as well as in queer darlings like Xena, He-Man, and Jem. While scholars have written sporadically about the queerness of such TV, the unexamined element throughout each that I bridge here is an introduction to how the syndicatedness of those shows encouraged their queerest aspects.

Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman focuses on the eponymous blue-collar housewife, a mother enduring a reality of failed promises—everything from the floor polish that accretes a waxy yellow buildup beneath her feet to a lifetime of unrequited sexual desire and unfulfilled happiness. Piercing through her continuous struggle to reproduce the perfectly gendered life she watches on her kitchen television set, Mary’s ennui bubbles up in involuntary vocalized gasps so heartbreaking and familiar to me as a queer person, it feels like they expose my darkest secrets while shredding me down to the bone. She’s at odds with everything, yet trying not to be.

Mary Hartman started life as a failure. At the time he pitched the show, creator Norman Lear was producing five of the top ten highest-rated network shows on television. Despite his recorded successes, however, all three networks passed because Mary Hartman was “too weird” with its unstable genre that mixed conventions of the sitcom, drama, and soap opera with Lear’s frank depictions of social issues, specifically here, those related to sexuality. So Lear took it to television’s last refuge of failure, syndication, and there it became a phenomenal success for the mostly independent stations that picked it up. Newsweek called it a “sort of video Rorschach test for the mass audience”[2] while Ms. Magazine’s review said that its “melodramatic pileup of calamities is outrageous.”[3]

Lear’s network shows like All in the Family, The Jeffersons, and Maude certainly pushed the cultural boundaries of television with “very special episodes,” but his syndicated shows serialized taboo stories into more comprehensive characterizations. Whereas “very special episodes” engender a patriarchal tradition of capturing and restraining potentially subversive content that could challenge a heteronormative order, the serial rarely finishes and a return to sitcom stasis is indefinitely deferred. Mary Hartman’s director Joan Darling once hilariously described this delayed gratification and extended queer time saying “it’s like screwing forever and never being able to come.”[4] Without network brass to contend with, in syndication Lear and his writers could really explore experimentation, genre, and identity play.

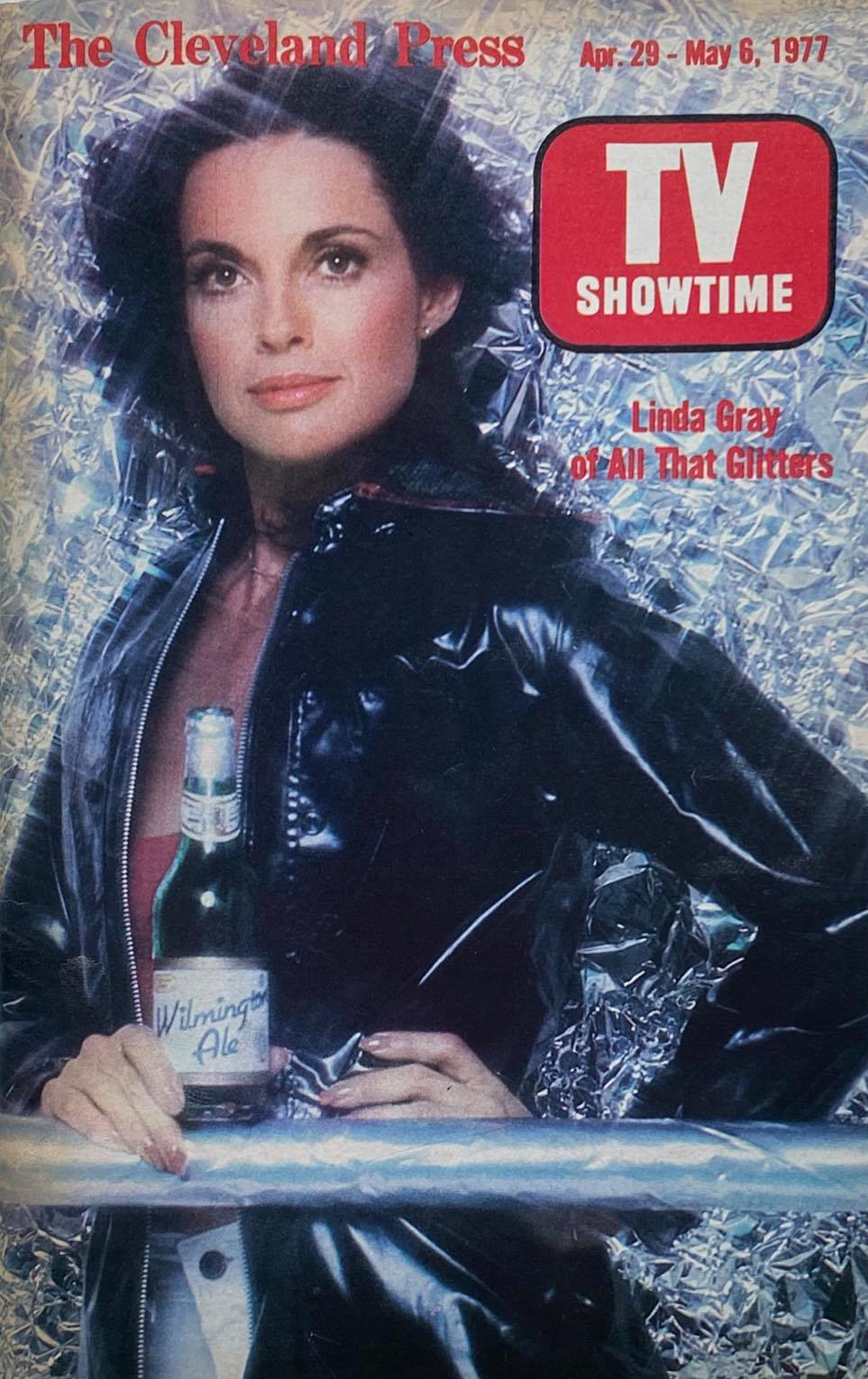

Over the course of dozens of episodes, Mary Hartman alone serializes the coming-out stories of a gay couple, a throuple, and at least three different bisexual characters all eventually leading up to a same-sex kiss shared by Mary and another woman—17 years before Roseanne did it with great fanfare in a “very special episode” on ABC. Lear’s second syndie serial All That Glitters (most often paired with Mary Hartman), meanwhile, featured a trans character in a leading role—an achievement American television would not reproduce for nearly 40 years—granting her 15 episodes to serialize her struggles against the cultural norms of gender identity and sexual liberation in the 1970s with an additional 36 episodes dedicated to her subsequent relationship and eventual marriage.

But for Lear, going for it was as much about strategic programming as it was creative expression. Like the syndie tabloid talk shows before him learned, the easiest way to compete with network budgets was to venture into the kind of programming they never would. Headwriter Ann Marcus even recorded in her autobiography that Lear’s most common direction for them was to “be as outrageous as possible.”[5] Mary Kay Place, who plays Loretta Haggers on the show, had previously worked with Lear in the writers’ room of his network shows and was struck by the difference between the productions. “Because we were syndicated, we didn’t have the box of Standards and Practices that the networks had … We had freedom to create. We were bad. We were good. But we did amazing stuff.”[6]

Out from under the watchful eye of a centralized network, its stifling censors, and typical S&P advertisers (as a syndie show filled by local commercial time), the writers answered only to themselves and the syndicating stations, which both Lear and Lasser told me only requested one edit in a 325-episode run. Queer issues and explicit stories about feminism and sexuality became dependable go-tos for garnering more viewers in the 1970s, be they fans or hate-watchers. One station manager reportedly called Lear to cheerfully report, “I’ve got 75 people marching on my station this afternoon to protest Mary Hartman. I love it!” [7]

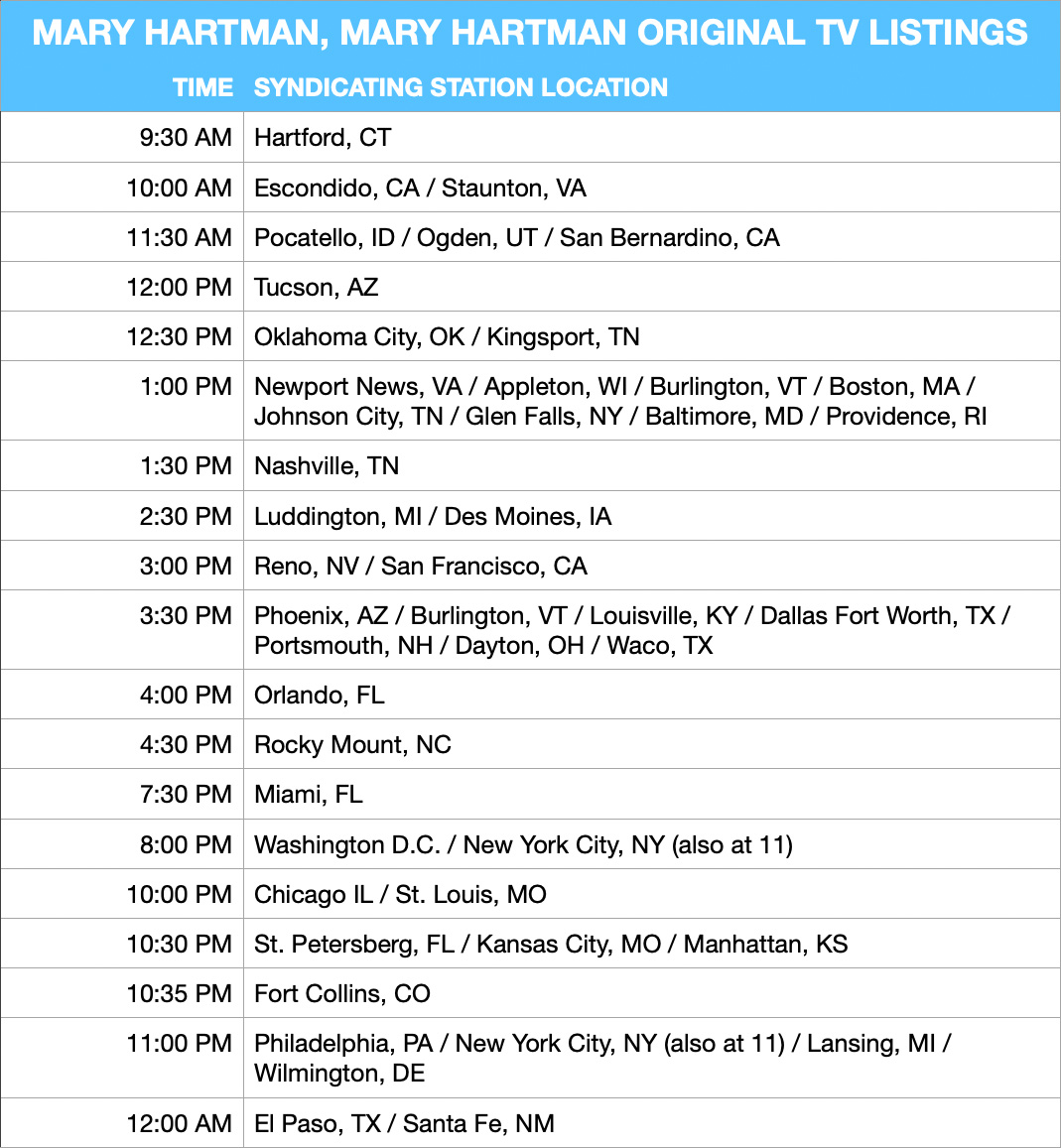

Every bit as much as the show flourishes in the liminal spaces between traditional television genres, its syndicatedness freed producers and station managers from bearing the network burden of audience ubiquity in television’s famously gendered programming line-up. Although Mary Hartman is typically described as a late-night show, its original local listings don’t exactly bear that out and illustrate how different stations experimented with different kinds of audiences in a television schedule that has always been highly gendered.

In many markets, it counter-programmed the news or late-night talk shows. But in New Hampshire and San Francisco, it ran opposite Porky Pig, in North Carolina opposite Sesame Street, in Orlando against reruns of Hopalong Cassidy, and in Des Moines it originally took The Mickey Mouse Club’s spot. Mostly missing primetime, syndicated programming like Mary Hartman has to be flexible enough to succeed in a variety of time slots—to function both as narrowcasting and as broader-casting—which make it prime for queer audiences and latchkey kids watching television without parental supervision. As a result, producers of syndie programming commonly explore different kinds of identities and genres for their shows and characters. Xena: Warrior Princess, for instance (which I watched as a teenager on Saturdays after Soul Train) featured a silly parody of the movie Clue in one episode and in the following week, Romans crucified Xena and her ambiguously lesbian partner Gabrielle. Battle on, Xena![8]

In serving the marginalized schedule and the oddball audience, syndication itself has been analogous to queerness in many ways. It is liminal, flexible, on the outskirts, in between, bordering, surrounding, apart from, and peripheral. It can seem silly, forgettable, unworthy, but also scandalizing and debased. It can and does transgress or subvert ideologies and intervene in cultural discourses. It can defy categories even as it can also cement them. While neither Mary Hartman nor All That Glitters were the first scripted syndies, they did beget a number of genre-bending, glittery, and excessively provocative programming that characterized much of the syndie offerings proliferating in the 1980s and early ‘90s. And while we are quick to herald the queer pioneering of streaming television today, a cultural history of syndication reveals a kind of synergy between syndication and queerness that streamers are really borrowing—from their numerous reboots to pick-ups of network rejects and even based-ons like Glow. Syndie TV was not so much ahead of its time but of its time and like regular television, only, “a little dirtier.”

Image Credits:

- “Episode 177” from DVD boxset of Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman (author’s screengrab)

- San Antonio Express’ review of Mary Hartman notes how the syndie serial skirted traditional network censorship. (author’s personal collection)

- Author’s Instagram compilation video of Mary Hartman’s gasps

- After Mary Hartman’s quick success in first-run syndication, Norman Lear and Ann Marcus created a new show called All That Glitters in which the cultural power of the sexes was always already inverted and women ruled the world. It featured Linda Gray in the role of Linda Murkland, a trans woman and model for the diegetic ultra-feminine Wilmington Woman Ale campaign, the show’s upside down version of our ultra-masculine Marlboro Man. Cover of the author’s copy of TV Showtime from The Cleveland Press, Apr. 29-May 6, 1977. (author’s personal collection)

- Syndicated TV listings for Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman (author’s graphic)

- Xena: Warrior Princess is mostly an episodic series, but it serializes a storyline of the characters’ growing relationship as subtextual lovers. Pictured is their child, immaculately conceived by Xena and a female angel. Picture from https://xenagateguard.tumblr.com/post/75102795836/xena-gabrielle-baby-eve

- Mary is writing these journal entries for a memoir by Gore Vidal, no less. [↩]

- Waters and Kasindorf, “The Mary Hartman Craze.” Newsweek, May 3, 1976. [↩]

- Harrington, Stephanie.“Mary Hartman: The Unedited, All-American Unconscious.” Ms. Magazine, May 1976. [↩]

- McCormack, Ed.“BB Shot Wounds, Whiplash, Storms of Weeping, Traumas That Shouldn’t Happen to a Dog! They’re All Part of the Real-Life Story of Mary Hartman’s Secret Recipe for Mock Cornball Surprise.” Rolling Stone, March 25, 1976. [↩]

- Marcus, Ann. Whistling Girl: A Memoir. Los Angeles: Mulholland Pacific Publishing. 1998. [↩]

- Wszalek, Arlene. Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman: Inside the Funhouse Mirror. Documentary. Authorized Pictures, 2008. [↩]

- O’Hallaren, Bill. “A Cute Tomato, A Couple Slices of Baloney, Some Sour Grapes, A Few Nuts …” TV Guide, June 19, 1976. [↩]

- Xena: Warrior Princess parodies many different films besides Clue, like Footloose, Groundhog Day, and Indiana Jones). It plays with various genres (dramas, serials, westerns, Kung Fu films, screwball comedies, talk shows, religious, and musicals) and subversively revises important cultural events such that Xena becomes their central figure, including David’s defeat of Goliath, the fall of Julius Caesar, the Trojan War, the wild west, the unchaining of Prometheus, the story of Pandora, the discovery of electricity, the rise of Christianity, and the events of A Christmas Carol, Antony and Cleopatra, and The Odyssey. [↩]

This was a great read, thank you! As someone who grew up in a conservative environment to be a liberal lesbian feminist, and who absolutely loved MH2 (even though I was only six), I feel all of this.

I’ve dressed as Mary Hartman for Halloween at least a dozen times over my life and no one has ever recognized the costume, or remembered the show. I’m so grateful to the internet for reassuring me that I didn’t dream Mary and her teeth-wiping, worried stare.