Are two heads better than one? Creative collaborations and job sharing in the media industries

Eva Novrup Redvall / University of Copenhagen

One of the pleasures of writing a research blog rather than a research article is the possibility to explore potential avenues of research while new ideas are still in progress. Accordingly, this blog reflects on notions of creative collaborations, joint authorship, team writing, directing duos, and job sharing, outlining a line of interest in my previous research and possible new paths to explore. Research blogs can be a productive way to start writing about new topics as well as an attempt to discover other scholars or industry practitioners out there with shared interests and exciting perspectives or case studies. The following is thus intended as an exploration of emerging research thoughts as well as an invitation to others who are fascinated by the intriguing world of screen production and the creative collaborations and complex working lives of industry practitioners.

To set the scene, quite some time ago an interest in the creative collaborations between directors and screenwriters in Danish filmmaking led me to do a PhD on this topic. My curiosity was driven by questions around who has the original idea and how that idea develops into a final screenplay and film. I was interested in the different steps and discussions of quality and value of the process and in finding out more about who was involved — and who was credited for their contributions.

The final thesis built on theories of creative collaborations [1], different degrees of collective authorship [2], and frameworks for understanding creative processes [3]. Based on two extensive case studies following new feature films from the beginning “mess-finding stages” to their cinema release, the thesis showed how the traditional auteur thinking in Danish filmmaking meant that, even when directors and screenwriters collaborated very closely, there was always a clear sense of the director as artist while the screenwriter was seen as more of a craftsperson helping the vision of the director come alive.[4]

After the thesis, I became interested in the making of television fiction such as Borgen and Forbrydelsen/The Killing. Even as ideas of “one vision” (allocated to a series’ head writer) and new talk of “showrunners” began to emerge in Danish production frameworks, screenwriters of scripted television seemed to enjoy a remarkably different position than in feature films. What were the workings of these creative ‘team writing’ collaborations? How should one think of authorship and agency in writers’ rooms, and what was the role of the director in this set-up?

While Netflix and HBO launched SVODs in Scandinavia and still more audiences started exploring international “complex TV” fiction [5], I tried to make sense of the Danish mode of production as a particular Screen Idea System that was definitely inspired by what was happening abroad, but still solidly anchored in a particular small nation public service television culture [6]. In line with other international developments, this study documented that screenwriters of television drama held a much stronger position than film writers — but a clear trend of singling out one person as the creator, despite the collaborative nature of the writing process and the many people involved along the way, has endured.

My observation studies and research interviews supported that popular Danish series were based on original ideas of the head writers who held final creative decision-making power and were respected as “one vision creators” during the highly collaborative writing and production processes. However, studying the making of television series made me think more about not only the creative collaborations but also the stressful nature of much work in the creative media industries.

The writers’ rooms that I studied were marked by reasonable working hours and good working conditions, but that is not always the case. Moreover, still more industry discussions have begun addressing issues of diversity and inclusion. Who gets to work in these industries — and who doesn’t — for various reasons? Are the established schedules and structures a challenge for certain people or for being at a certain stage in life, for instance for a single parent with small children?

After studying the writing and production of fiction for children and young audiences for several years and their new ideas of co-creation (see my previous Flow column), I have thus started looking into alternative ways of thinking about work in the media industries and creative collaborations, exploring issues around work/life balance as well as diversity and inclusion. Currently, I find the notion of job sharing intriguing in this regard, not only from a practical and labor perspective, but also in terms of theoretical discussions around creative collaborations and authorship.

There is an important and vibrant field of studies into media work and labor issues that I don’t have room to engage with in detail here, such as David Hesmondhalgh and Sarah Baker’s study of good work vs. bad work [7] or edited collections on ‘media work’.[8] The past years have also seen inspiring industry initiatives emerge, trying to challenge the traditional ways of thinking about and organizing work in the film and television industries.

Several of these initiatives are based in the UK and focus on how to balance being a parent with working in the screen industries. Some of these initiatives are mostly about raising awareness through sharing stories, resources, training, and research, such as Raising Films‘s mission to “support, promote and campaign for parents and careers in the UK screen sector”, or Cinemamas, a community for mothers working in the screen industries intended as “a peer support group for advice and conversation” that champions “inclusive working practices such as job sharing and flexible work”.

The issue of job sharing became still more prominent, during the 2010s, for instance through the website Share My Telly Job that ran from 2015–2023 “to help people work more flexibly in TV and film, with job-sharing at its core”, TakeTwo, which was established at the Edinburgh Film Festival in 2019 to support and promote job-sharing, or very concrete job-sharing websites such as Mediaparents that tries to aggregate postings for flexible jobs in TV in one place and Thecallsheet that writes about job shares as one part of connecting film & TV industry professionals.

Many of the job sharing examples mentioned online are in art departments (as described by Thecallsheet) or for jobs such as location coordinators (as exemplified by WIFTNZ 2023), but there are also case stories about directors who job share [9]. Looking at recent film history, there are famous examples of brothers working closely together in various ways, like the brothers Coen, Dardenne, Duplass, Farelly, Russo, or Safdie (as well as the Wachowsky sisters) or directing duos such as “The Daniels” behind Everything Everywhere All at Once. It is still rare two see two people co-directing, but the directing duo Bert and Bertie (Amber Templemore-Finlayson and Katie Ellwood) is a current, inspiring example of two women directors working together and finding acclaim for their work on high-end television drama such as Hawkeye and Lessons in Chemistry.

While job sharing can be about quite practical and logistical concerns [10], it can also be about creative partnerships. However, as discussed by UK directing couple Mathy and Fran or the Swedish screenwriting sisters Sofie and Tove Forsman at the recent children’s film festival BUFF in Malmö, there can be several challenges to being hired as a team – not the least expecting to be paid as two people rather than one. From my perspective, it seems fruitful to trace and analyze the strengths and weaknesses of new forms of job sharing initiatives in more detail in the coming years, with a focus on issues of work/life balance, diversity, and inclusion, as well creative perspectives.

Numbers from 2020 point to the way that only 14% of women in the UK film and TV industry were parents, compared to 75% across the UK as a whole. Launching a new job sharing initiative in the wake of this news, Sarah Lee of The Talent Manager argued that “for all its creativity, the TV industry has often not been very creative when it comes to thinking about recruitment” [11]. It seems like this might be gradually changing — and this seems worthwhile to study, for a small nation as well as with a transnational perspective. Do get in touch if you share this research interest.

Image Credits:

- Television writers’ rooms have several writers working together on the same projects. But what does more regular job sharing look like in other parts of the film and television industries, e.g. if directors decide to work together as co-directors? Source: Illustration of collaborative television writing process by Malin Redvall.

- What goes on behind those red glass walls? A photo from outside the writers’ room of the political drama series Borgen at the Danish Broadcasting Corporation DR in Copenhagen from the time of the writing of the third season. Source: author’s photo.

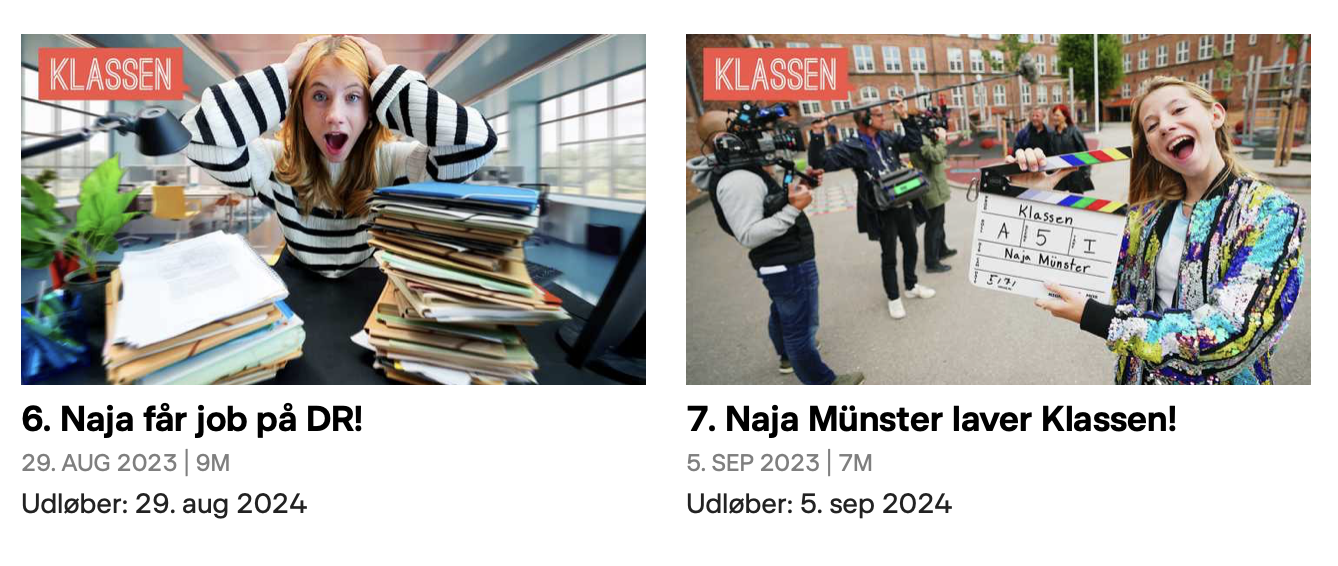

- The Danish children’s series Klassen has worked with different forms of co-creation with children for many years, for instance by involving junior editors and, most recently, by involving a young influencer such as Naja Münster. Source: Screenshot of material around Klassen episodes with Naja Münster from the DRTV website.

- Since 2015, the community interest company Raising Films has been focusing on better working practices in the UK screen sector, offering a range of research and resources on topics such as job sharing. Source: Screenshot from the Raising Films website.

- The directing duo Bert and Bertie (Amber Templemore-Finlayson and Katie Ellwood) is currently an inspiring example of two women directors working together on high-end productions. Source: @Bertiesbertdirectors on Instagram.

References:

- John-Steiner, Vera. 2000. Creative Collaboration. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [↩]

- Gaut, Berys. 1997. “Film Authorship and Collaboration.” In Film Theory and Philosophy, Richard Allen & Murray Smith. Oxford: Clarendon Press; Sellors, Paul C. 2007. ”Collective authorship in film.” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 65 (3): 263–271 [↩]

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. 1999. “Implications of a Systems Perspective for the Study of Creativity.” In Handbook of Creativity, edited by Robert J. Sternberg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [↩]

- Redvall, Eva Novrup. 2010. Manuskriptskrivning som kreative process: De kreative samarbejder bag manuskriptskrivning i dansk spillefilm. PhD thesis from The University of Copenhagen. [↩]

- Mittell, Jason. 2015. Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling. Oxford: Oxford University Press [↩]

- Redvall, Eva Novrup. 2013. Writing and Producing Television Drama in Denmark: From The Kingdom to The Killing. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [↩]

- Hesmondhalgh, David, and Sarah Baker. 2011. Creative Labour: Work in Three Cultural Industries. London Routledge. [↩]

- Deuze, Mark, and Mirjam Prenger. 2019. Making Media: Production, Practices, and Professions. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [↩]

- Cinemamas. 2023. “Who said directors can’t job share.” Cinemamas.co.uk, December 1. https://www.cinemamas.co.uk/blog/who-said-directors-cant-job-share [↩]

- Newsinger, Jack, and Helen Kennedy. 2022. “’Better workplaces are good for everyone’: An interview with Natalie Grant of SMTJ about motherhood, working in television and the Covid-19 pandemic.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 24: 132–145. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.24.08 [↩]

- Televisual. Staff Writer. 2020. “TV industry job share initiative launched.” https://www.televisual.com/news/tv-industry-job-share-initiative-launched_nid-8588/ [↩]