Visual Pleasures in Magic Mike’s Cinema

Nicole Erin Morse / Florida Atlantic University

It’s reductive, but whenever I teach Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” one of the most important concepts I want my students to grasp is Mulvey’s argument about how the male gaze is produced structurally. Rather than simply asking whether a woman is displayed on screen, Mulvey discusses how the male gaze unifies three looks: the camera, the spectator, and the male character who acts as a stand-in for the spectator.[1] I value this insight because of its specificity, and because it attends to how film form interpellates us as spectators. Perhaps more importantly, by analyzing the formal structures that construct looking relationships in film, it becomes possible to move beyond just identifying the hegemonic male gaze in classic Hollywood cinema to discover other dynamics of looking and being looked at within film, television, and other media.

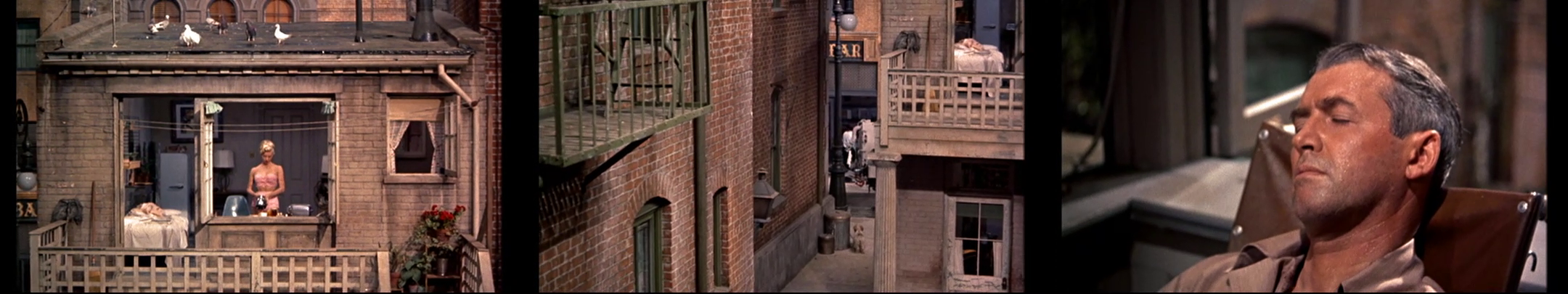

A classic example of the male gaze appears in Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954). In the opening shots of this narrative about an injured photographer watching people through his window, the look of the camera is aligned with the look of the spectator but is not grounded in the look of a male character within the film.

Instead, this roving look explores the space, moving past a ballerina in the apartment opposite to reveal the photographer, sleeping. But soon, this mobile camera is grounded in a shot reverse-shot structure where the camera angle approximates the on-screen character’s position, making it very clear that the camera, the spectator, and Jimmy Stewart’s character are all united in looking at this woman.

The gaze, which combines the simple act of looking with the complex and gendered dynamics of power, objectifies the ballerina in part because she is clearly unaware that she is being watched. As Mulvey notes, the fiction that the actress is somehow unaware of being observed is a critical part of the sadism of the male gaze.[2] In short, the man looks, the woman is looked at, and she is unaware of his gaze.[3]

But what happens when the genders are reversed? Is a female gaze possible? Mulvey suggests that it is not, and her manifesto argues that destroying visual pleasure is the most effective tactic for a feminist avant garde.[4] Meanwhile, Mary Ann Doane points out that—in a patriarchal society—a reversal always reminds us insistently of the status quo.[5] Objectifying men merely reinforces our knowledge that women are the usual objects of the gaze.

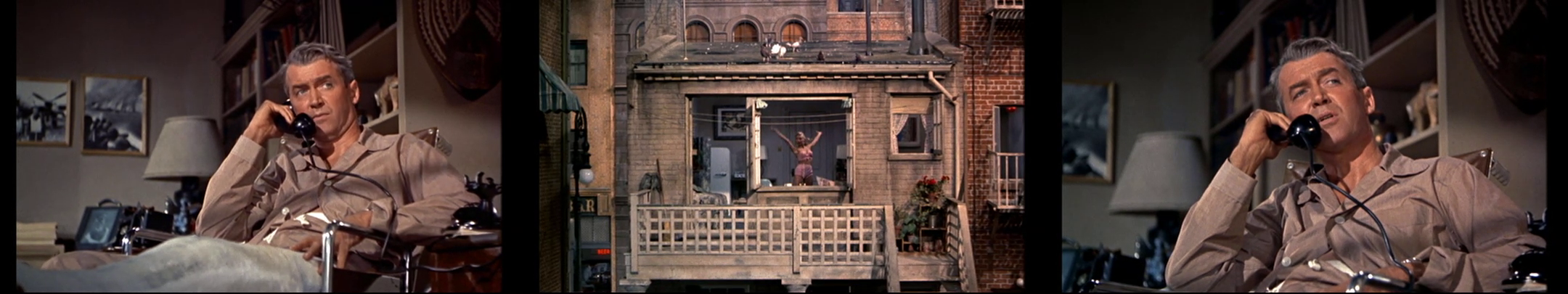

This dynamic is apparent in Magic Mike (2012) and Magic Mike XXL (2015), a film series that purportedly caters to heterosexual female desire. However, the looking relationships in these films are structured in ways that undermine female desire—in order to produce a more complex set of affective pleasures than the sadism or fetishism Mulvey identifies in the male gaze. Let’s start with the first musical number in Magic Mike, “It’s Raining Men.” In this performance, the cast of male dancers perform for a mostly female crowd who we might think are stand-ins for the spectator.

Yet none of these women in the audience actually serve as surrogates for the spectator, for our look and the look of the camera is never aligned with any of the female characters. Instead, the camera moves fluidly around the dancers, capturing their performance from multiple angles.

The camera is always above the audience, giving us a privileged look at the spectacle rather than unifying the three looks of camera, character, and spectator. The women are mostly present as sound only—their screams of delight stand in for their presence, reminding us of the way that female sexual pleasure is so often located in aural rather than visual signifiers.[6]

Ultimately, the formal strategy of shot reverse-shot editing locates the agent of the look in the film’s central protagonist: newcomer Adam, who watches the performance from the sidelines. The fact that he is watching the performance is revealed by a shot from his perspective followed by a close up of him looking toward the stage; it is underscored by a lighting effect that illuminates him, pulling his curious and desirous look out of the shadows.

As a result, the scene doesn’t exactly construct a female gaze. Visual pleasure is arguably available to female spectators viewing this scene, but the looks of the on-screen women are ultimately subordinated to the look of a man. Doane points out that even when the three looks aren’t unified, formal structures can still produce a kind of male gaze—or at least a gaze that cancels out the possibility of a female look. She supports this argument through a close reading of a photograph that depicts a woman looking at an unseen painting, while the man beside her on frame right looks across the photograph to stare at a female nude on frame left.[7]

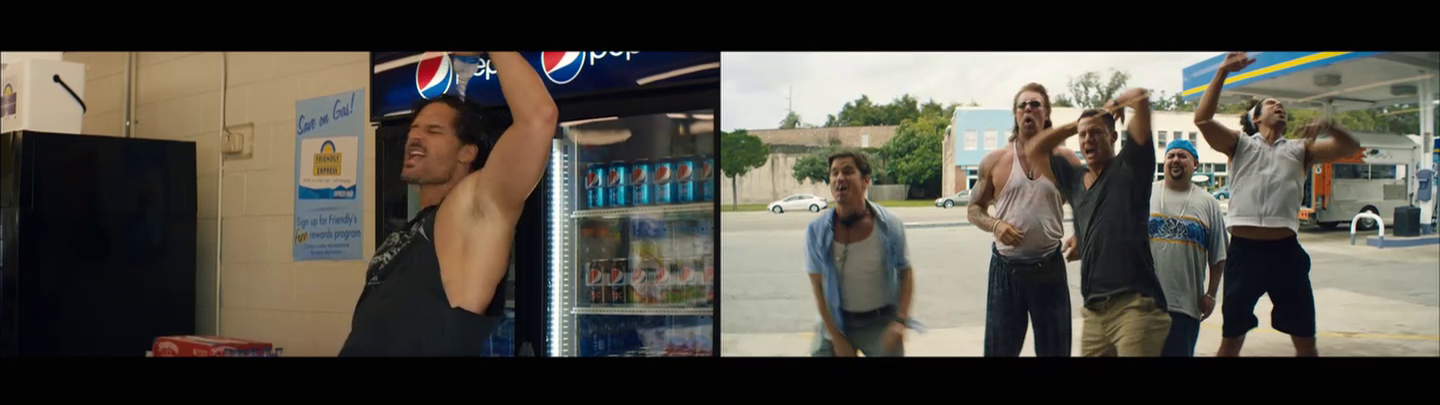

The sequel Magic Mike XXL uses formal structures similar to the original film to produce a homosocial gaze while also staging a kind of “dirty joke” at the expense of the woman who might otherwise be the ostensible agent of the look. In this sequel, the male dancers confront a crisis of confidence in one member of their crew, Big Dick Richie. To build back their friend’s confidence, they challenge Richie to make a dour-faced gas station clerk smile. The subsequent musical number, set to The Backstreet Boys’ “I Want it That Way,” features a variety of looking relationships structured through shot reverse-shot editing.

At first, the clerk is unaware of Richie while he attempts to get her attention. He looks at her, and she doesn’t look back. Clearly, however, she is not the object of an erotic gaze; instead, her refusal to look becomes the challenge he must overcome as he turns himself into an erotic spectacle. As he dances to the back of the store, he is followed eagerly by his friends who watch him through the window.

Although the clerk is supposedly the audience for this performance, formal structures keep reminding us that Richie is ultimately trying to prove something to his friends. Shots of the woman looking are continuously intercut with shots of Richie’s friends outside the window while shot reverse-shot editing aligns us more closely to their look at him than to hers.

There is only one true shot reverse-shot sequence that is actually grounded in the clerk’s perspective, but her look is partially obscured by the counter.

More importantly, the smile Richie manages to elicit isn’t the culminating peak of the scene’s energy. Instead, what really matters is his friends’ ecstatic response.

Despite the many opinion pieces claiming that Magic Mike cultivates a “female gaze,” the formal structures within these films actually maintain the importance of the male protagonists’ look and formally block or cancel the look of the diegetic female characters. Yet perhaps the more important lesson isn’t that patriarchy finds a way to deny heterosexual female desire. Rather, this close analysis reveals that the pleasures of these films cannot be explained as a simple reversal of the male gaze. They do not align our look with the look of a desiring woman. Instead, these cinematic narratives exceed the sadism of objectification and attune us to other visual pleasures.

Image Credits:

- Newcomer Adam watches the male dancers perform in Magic Mike (2012) (author’s screengrab).

- The opening shots of Rear Window (1954) (author’s screengrab).

- The male gaze in Rear Window (author’s screengrab).

- Male dancers perform to “It’s Raining Men” in Magic Mike (author’s screengrab).

- The camera offers multiple angles of the performance (author’s screengrab).

- A wide shot from Adam’s perspective is then grounded in a medium close up of his look (author’s screengrab).

- Big Dick Richie performs for a gas station clerk in Magic Mike XXL (2015)… (author’s screengrab)

- …but he is actually performing for his friends (author’s screengrab).

- As Doane suggests, form blocks the woman’s look – at least partially (author’s screengrab).

- Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Screen, Volume 16, Issue 3 (Autumn 1975): 12. [↩]

- Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure,” 9. [↩]

- Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure,” 11. [↩]

- Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure,” 8. [↩]

- Mary Ann Doane, “Film and the Masquerade: Theorizing the Female Spectator,” in Femmes Fatales: Feminism, Film Theory, Psychoanalysis (New York: Routledge, 1991), 21. [↩]

- John Corbett and Terri Kapsalis, “Aural Sex: The Female Orgasm in Popular Sound,” The Drama Review, Volume 40, Issue 3 (Autumn 1996): 102-111. [↩]

- Doane, “Film and the Masquerade,” 29. [↩]