Black Widow Won’t Save You: Labor and the Streaming Frontier

Kate fortmueller / University of Georgia

In the climactic scene of Black Widow, Natasha Romanoff (Scarlett Johansson) hurdles through the sky to defeat the evil general and liberate the women who had been human trafficked into Black Widows. As is common in superhero narratives, the heroics of the few save hundreds in a singular epic battle. Once the credit scroll begins, the acrobatics of the stars are replaced by a cascade of worker names—a reminder of the many who enable on-screen heroics with daily feats of strength. If we have learned anything during the pandemic, it is that individual heroics rarely fix large societal and structural problems. This common critique of superhero narratives is perhaps the single most valuable lesson Hollywood workers must carry into the streaming era.

For Hollywood labor, earning fair compensation in the digital landscape has been a long-running war with multiple small battles. Writing about the WGA strike in 2007, Miranda Banks and Ellen Seiter (2007) contextualized the fight as an ideological clash between the “entrepreneurial” values of Silicon Valley and a unionized Hollywood. Fourteen years later, Hollywood workers are not just fighting for residuals; working conditions have broadly deteriorated, as they encounter a wide array of remuneration issues and unsafe conditions. In the wake of the pandemic, two major labor conflicts – Scarlett Johansson’s complaint against Disney and the fraught negotiations between IATSE (International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees) and the AMPTP (Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers) – reflect the changes and upheavals of an entertainment industry in transition. On the surface, these two labor disputes could not be more different: Johansson is a global superstar concerned about her multimillion-dollar bonus, while IATSE represents crew members who are advocating for a living wage and more humane working conditions. However, it might be more productive to see these disputes as related, as they are both symptomatic of key institutional growing pains.

The rapidly escalating transition into streaming as the dominant mode of distribution was only exacerbated by the pandemic. In Hollywood, workers adapted not only to pandemic closures, but their work changed in response to broad shifts in media consumption patterns—particularly to a widespread reliance on streaming services. The COVID-19 pandemic upset tried-and-true Hollywood business practices, but none of the changes garnered as much public speculation as the collapse of the theatrical release window and temporary closures of movie theaters. In April 2020, Universal shattered the industry standard three-month theatrical window for premium releases by rolling out Trolls World Tour as a $19.99 PVOD (premium video on demand) and limited theatrical release. Day-and-date releases continued throughout the summer, with many smaller films following suit and Disney deciding to release Mulan day-and-date in limited theaters and on Disney+ for a $29.99 surcharge. As I (2021) have written about elsewhere, the pandemic gave studios and distributors reason to experiment with day-and-date releases for big budget films and led them to prioritize their streaming services to salvage their fiscal years as COVID-19 raged throughout the summer.

The collapse of release windows is just one aspect of the changing distribution strategies that journalists dubbed the “streaming wars,” a term that describes the growth of digital distribution services as a battle over market share. Amanda Lotz (2020) has nuanced this term, pointing out that the “wars” are often mischaracterized as a domestic battle when they are more appropriately understood as a fight involving different multinational battles. In the war over subscribers, there are no casualties (except for poorly conceived endeavors such as Quibi): just churn, fluctuating share prices, and consumer disruption. However, rather than telling the story of streaming as a dramatic battle between powerful conglomerates, we need to consider the consequences of these structural and technological changes for creative labor.

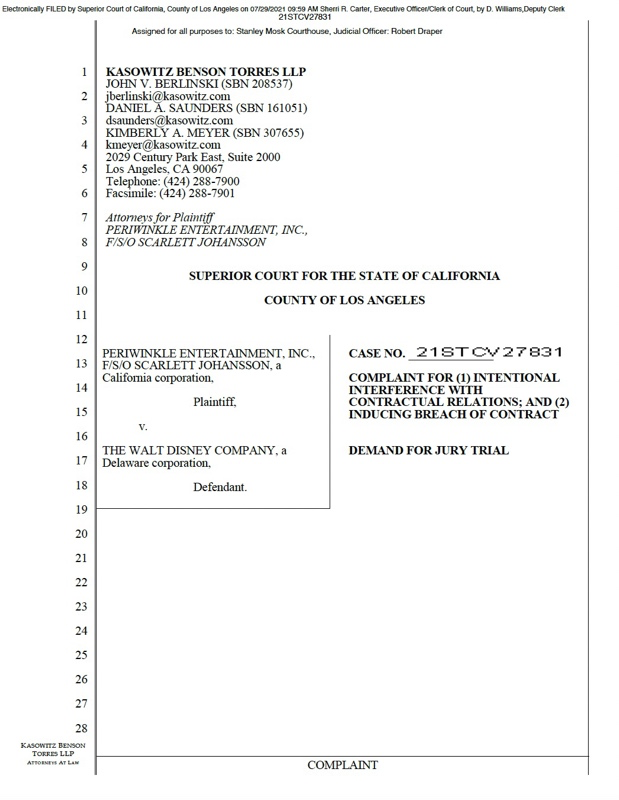

For stars and top talent, the ramification of streaming comes in the form of lost bonuses. On July 29, 2021, Scarlett Johansson’s representatives filed a breach of contact complaint against Disney for releasing Black Widow day-and-date in over 4000 theaters and on Disney+. In the complaint, Johansson’s lawyers painted Disney as a conspiratorial and greedy villain, explaining that they intended to “lure the Picture’s audience away from movie theaters and towards its owned streaming service, where it could keep the revenues for itself.” Black Widow was by no means the first blockbuster to get a day-and-date release in the pandemic, but this lawsuit marked the first sign that talent would offer legal push back after over a year of shifting release dates, significant losses, and contract buy-outs. Contracts for top-end talent and the unions’ collective bargaining agreements were not negotiated with pandemic pivots in mind and deals such as Johansson’s are built around theatrical exhibition grosses. Although it is hard to garner sympathy for Johansson’s lost bonus, her team negotiated these terms based on an understanding of the film’s release strategy. If studios can withhold information or change release strategies, this gives them tremendous power over talent.

Anger over changes to release strategies had been simmering for months. Mega-agency CAA (Creative Artists Agency), who also represents Scarlett Johansson, had a swift response to WarnerMedia’s decision to bypass theatrical distribution in December 2020. In an openly critical letter to Warner CEO Jason Kilar, CAA leadership explained: “The bottom line is that you are trying to take advantage of our clients to benefit your company. Neither we nor our clients will stand for it.” Although WarnerMedia reportedly bought talent out of many deals, other studios such as Disney, did not make arrangements with talent when they released their films to streaming. Ultimately (and unsurprisingly), Scarlett Johansson and Disney settled this squabble confidentially and out of court, keeping journalists, scholars, and audiences in the dark as to the particulars. Johansson’s lawsuit belongs to a longer history of women in Hollywood that Emily Carman (2016) details in Independent Stardom; in the wake of this dispute, those familiar with Hollywood history have also rightfully pointed out the similarities between Johansson’s case and Olivia DeHavilland’s successful lawsuit against Warner Bros. However, in the current lineage of labor versus digital distribution, this individual victory for Johansson undoubtedly bolstered CAA’s arsenal for future negotiations in the streaming era.

In contrast, the IATSE negotiations, which targeted unsafe working conditions as they aim to treat remuneration, harken back to a different earlier moment in Hollywood history when unions struck about labor conditions rather than residuals (which have been the focus since the introduction of commercial television). IATSE’s demands seemed overdue, crew have long endured dangerous and grueling hours, and the union has provided streamers with time to build their businesses before asking for rate increases. IATSE’s negotiations over breaks, increased compensation on projects deemed “new media” (which “is not so new anymore” and covers an array of productions for the streamers), and their benefits and pension packages began in May, collapsing in September and leading to a strike authorization vote that demonstrated the union’s overwhelming desire for change. IATSE locals (which are branches in the union divided along craft lines) have shown overwhelming support for the union and continued to push a resistant AMPTP on these terms. The cumbersome IATSE negotiations differ from the swift response and resolution Johansson obtained. These two struggles also differ in order of magnitude: Johansson’s deal will shape future contracts, but if IATSE is able to change hours, film production will be radically altered. As of this writing, IATSE has ratified their tentative agreement with the AMPTP by a narrow margin, and a vocal contingent feels these terms are insufficient and will not portend the happy ending Johansson achieved.

The Scarlett Johansson legal dispute and the fraught IATSE negotiations are very different types of labor conflicts, yet both illustrate ways that power of talent and labor have been eroded in the digital landscape. For scholars of Hollywood as an industry, this perspective on streaming is an important counternarrative to dominant conversations about the competition between services. The story of labor is a more fragmented story because it involves multiple social actors, variable stakes, several storylines, and no clear savior. Heroic figures often make for compelling protagonists, but in the history of Hollywood, transformative change comes from union solidarity.

Image Credits:

- 1. Natasha Romanoff’s individual heroics are a team effort from the below-the-line workers (author’s screen grabs).

- 2. Scarlett Johansson’s personal team filed a complaint against Disney on July 29, 2021 (author’s screen grab).

- 3. Protest slogans reveal labor’s longer battle over digital compensation. A young girl joins the WGA picket line during the 2007-2008 strike on the left (photo courtesy of Miranda Banks) and IATSE crafts a similar message on the Basic Agreement informational website on the right.

To exit without the answers to the difficulties you have sorted out through this guide is a critical case, as well as the kind which could have badly affected my entire career if I discovered your website.