Embodied Teaching and the Precarious Labor of Social Justice Media

Meera Govindasamy and Jonathan Petrychyn / Ryerson University

We knew that adapting an experiential, hands-on activist media course for online delivery would be a challenge. In the Winter 2021 term we were hired as contract lecturers at Ryerson University to teach Social Justice Media, a senior undergraduate/graduate seminar that encourages students to produce activist media and understand its context in Canada. The central feature of the course is a public-facing speakers series organized by the Studio for Media Activism and Critical Thought (SMACT) — a social justice research centre at Ryerson University. Students are required to participate in the three-part series and work collaboratively with activists to produce their own forms of social justice media. In previous years, students would respond to these speakers series events with short videos, toolkits, VR experiences, and other creative activist media outputs. The course was predicated on group work and on the ability to gather in person to create media that affects change. This group work became an impossibility in the COVID-19 pandemic. With access to technical equipment limited, a stay-at-home-order in place, and the possibility that some of our students would be taking the course in different time zones, we could not practically or ethically ask our students to create projects initially designed for in-person instruction.

As two people who have been involved with SMACT and the design of Social Justice Media both officially and unofficially over the years, we saw the course’s core strength as its ability to centre what Elspeth Probyn (2004) calls “teaching bodies,” or the practical lived experience of teaching as an embodied practice. In previous years, students enrolled in Social Justice Media experienced the contagious affect of speaker series events held in queer bookshops and theatre spaces, and they created affective pieces of media that often reflected their embodied experiences of identity. With this in mind, rather than recreate the in-person experience online, we redesigned the course as a meta-commentary on the process of teaching bodies and producing social justice media in an online space. In working through this problem of adapting an experiential course for online delivery, we were struck by how much the course itself is its own form of social justice media. In this way, Social Justice Media became a reflexive course about the challenges of developing accessible online activist media and learning experiences during a pandemic.

Adapting the course content to engage with activist media pedagogy posed its own challenges, particularly around our own commitments to the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and our rights and responsibilities as contract instructors at our university. While UDL advocates for the multi-modal delivery of course material, a labor rights perspective recognizes how this expectation creates more work for contract instructors without more compensation. Though they may be contradictory, considering both UDL and teaching labor brings bodies to the forefront of online learning. Bodies are implicated when instructors consider the needs of students as well as our own bodies as sites of precarious labor.

By considering the diverse needs of students in our Social Justice Media course using the principles of UDL, we have aimed to create opportunities for embodied learning within our virtual classroom. The central tenet of UDL is that rather than viewing students with diverse learning needs as a problem, curriculum ought to be flexible enough to accommodate students with varied learning styles, disabilities, and cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds. A curriculum designed with UDL in mind seeks to provide all students with multiple ways of learning and demonstrating their knowledge, instead of focusing on accommodating learners on an individual basis (Rogers-Shaw et. al., 2017).

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the principles of UDL have become a useful framework for creating learning environments that can accommodate the needs of students whose circumstances as learners are more disparate. In addition to factors like disability that affect student learning, students are now located all over the world, learning in vastly different home environments, and have unequal access to the internet and technology.

With the ideas of UDL in mind, and in an effort to engage with students’ embodied experiences of ability and disability, we adapted Social Justice Media to be flexible to the needs of diverse learners. We post our slides and notes on the course shell after lecture, and present ideas and information through readings, lecture material, class discussion, film, and audio podcasts. After realizing how often students were struggling with their internet connections, we started recording lectures to share with students in the event of technological mishaps. We decided not to post the recordings more publicly to the entire class in an effort to be mindful of everyone’s privacy in a participatory course that sometimes engages with personal subject matter. We also aimed to make opportunities for assessment as flexible as possible by allowing students to meet the participation requirement through engagement out loud, in the Zoom chat, or during breakout room discussions.

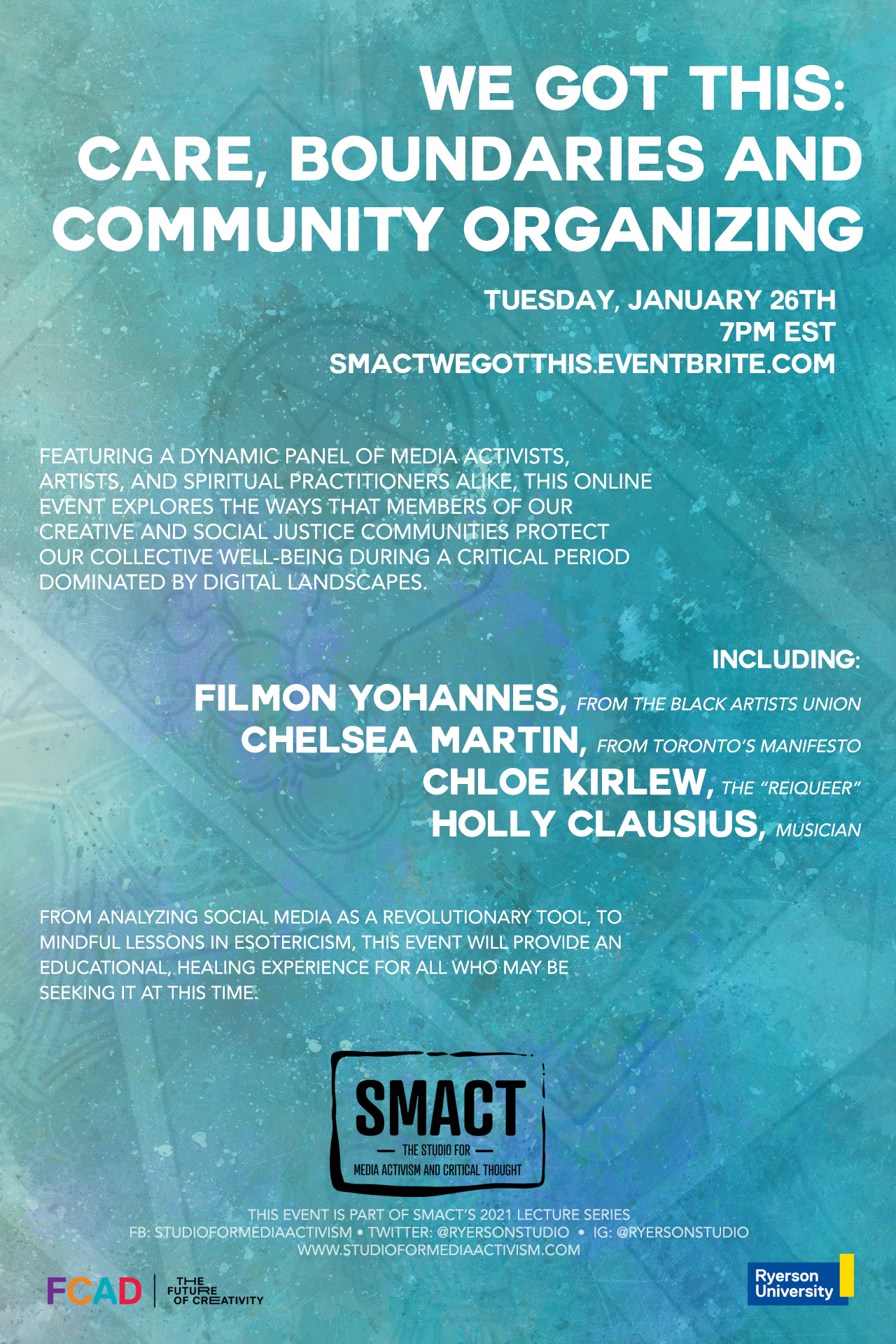

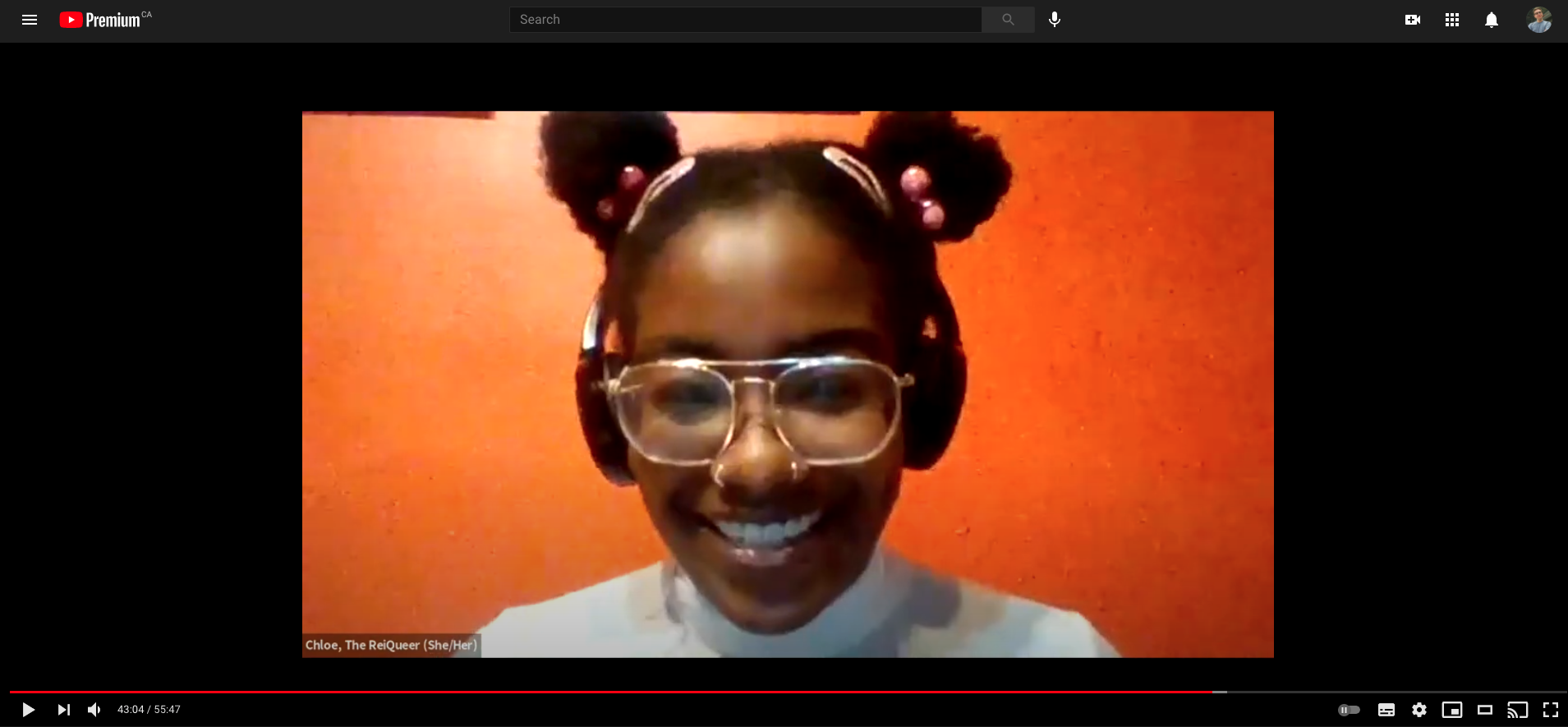

Beyond the formal mechanics of course delivery, we also adapted course content to engage with the dynamics of embodied learning during the pandemic. Bearing in mind the embodied learning needs of students facing the stress of a pandemic, the first speakers series event of the course focused on themes of care, boundaries, and community organizing. Our aim in this event was to assemble a group of artists, activists, and academics who could speak to the ways they are presently supporting their community’s activism and wellbeing. In addition to hearing more traditional panel presentations about online activism and organizing, the event featured a musical performance from Holly Clausius, a Toronto-based artist, as well as a guided meditation exercise with Chloe Kirlew, also known as The ReiQueer. In these instances, even over Zoom, students were engaged on an embodied and affective level. Throughout the musical performance, students commented in the chat with excitement and others bobbed their heads. During the guided meditation, the group turned off their cameras and had the opportunity to experience a collective sense of care for their bodies and overall well-being. Even without sharing physical space, by acknowledging our students’ need for rest, we were able to teach bodies. Probyn (2004: 35) suggests that “‘theory’ is routinely imposed as a way of precisely dampening the potential affect” within our classrooms. Our hope is that this opportunity for embodied, rather than strictly theoretical, learning was both a break for students who need it and an accessible means of engaging with theory.

As precariously employed contract lecturers, the extra teaching labor required to produce creative and accessible online learning is not lost on us. Retaining the speakers series as a core feature of the course, allowing for multiple forms of engagement and assessment, and adapting experiential learning strategies to an online environment requires a significant amount of labor that normally goes uncompensated as contract lecturers. As the Precarious Labor Organization of the Society for Cinema and Media Studies argues in their manifesto, “Contingent laborers cannot afford to perform the unpaid labor demanded of academics such as this” (Brasell et al. 2020). Very few of us have the time and economic privilege to develop the innovative, experiential courses that departments have come to expect. Indeed, our ability to continue including the speakers series as a central feature of this course is because we have received the support of SMACT, which is co-directed (alongside Meera) by Cheryl Thompson, a tenure-track professor at Ryerson University. That kind of institutional support has allowed Social Justice Media to retain its most unique and experiential features in its shift to online learning.

In an effort to directly address this conversation around the labor of online teaching in our classroom, we asked students to read about the principles of UDL and put them in conversation with Rebecca Barrett-Fox’s (2020) widely circulated blog post “Do a bad job of putting your courses online.” For Barrett-Fox, online teaching should start from an understanding that students and educators have more important things to deal with during a pandemic than online learning. As such, keeping online learning simple makes the experience more manageable for all. From a pedagogical perspective, we want students to confront their own expectations about online learning and draw their attention to the debates that have framed the form and content of their online learning environment over the past year. Decisions made about how to approach online learning are political and are informed by the economic positions of their instructors.

It is from these perspectives — accessible learning and labor rights — that we want students to understand this course as a form of social justice media. At the time of writing, we are a third of the way through the course. We have found this reflexive approach to the course online has, so far, proven successful in retaining the course’s experiential “teaching bodies” ethos. By making transparent the structures and limitations of adapting a social justice media course for online learning, and by recognizing that even online we are still teaching material, flesh and blood bodies we have found an affective solidarity with our students. The course itself has become an experiment in the affective longings that structure social justice media production in moments of crisis.

Image Credits:

- Promo Material from Speakers Series [Credit: Calla Evans]

- YouTube video of speakers series event [Credit: The Studio for Media Activism and Critical Thought]

- Chloe Kirlew, also known as the ReiQueer, leads a guided meditation exercise during our first speakers series session. [Credit: The Studio for Media Activism and Critical Thought]

Barrett-Fox, Rebecca. 2020. “Please Do a Bad Job of Putting Your Courses Online.” March 12, 2020. https://anygoodthing.com/2020/03/12/please-do-a-bad-job-of-putting-your-courses-online/.

Brasell, Bruce, Joseph Clark, Beth Corzo-Duchardt, Rebecca M. Gordon, Jamie Ann Rogers, Sharon Shahaf, and members of the Precarious Labor Organization. 2020. “Organizing Precarious Labor in Film and Media Studies: A Manifesto.” JCMS: Journal of Cinema and Media Studies 59 (4): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2020.0038.

Probyn, Elspeth. 2004. “Teaching Bodies: Affects in the Classroom.” Body & Society 10 (4): 21–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X04047854.

Rogers-Shaw, Carol, Davin J. Carr-Chellman, and Jinhee Choi. 2018. “Universal Design for Learning: Guidelines for Accessible Online Instruction.” Adult Learning 29 (1): 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1045159517735530.

I absolutely support this initiative as students should be active individuals. As for me, in my student years, you need to take more part in different events. Sometimes it’s even better to buy homework from the site and go to some kind of event than to sit the whole student life for textbooks.

Very useful and accessible written. thank you