Adiós, Gloria Delgado-Pritchett: Or Why Sofía Vergara Sometimes Makes Me Cry

María Elena Cepeda / Williams College

In the abrupt pandemonium that marked April 2020 and the first months of the devastating Coronavirus pandemic in the United States, a television milestone occurred that passed by relatively unnoticed: the end of Modern Family (ABC, 2009-2020), the highly popular, long-running comedic vehicle for 48-year-old US Colombian actress Sofía Vergara. Despite prior fame amongst Latin American and US Latina/o/x television audiences, the Emmy-winning Modern Family is the program that made Vergara, a native of Barranquilla, the largest port city on Colombia’s northern Caribbean coast, a household name across the United States. It also helped earn her the honor of being the US television industry’s highest-paid actress from 2013-2020.

Scholars in Media Studies and beyond have dedicated considerable attention to Vergara and her character in Modern Family, and their research informs my thoughts as I reflect back on the significance of Sofía Vergara and/as Gloria Delgado-Pritchett. Oddly enough, while US Colombian women in media and popular culture have long been a primary research focus of mine, I have never written about Vergara, despite her media prominence. Nor have I dedicated much deep thought to it; rather, I have read other’s work on her with interest, and have managed to keep myself informed of major developments in the show without ever becoming a regular viewer, given the program’s prominence in US popular culture. Only now, sitting down to compose this piece, do I better understand why I can only begin to write about Sofía-as-Gloria after the fact of Modern Family‘s ending.

Focusing on Gloria’s Spanish-accented English, scholars such as Héctor Fernández L’Hoeste (2017) have argued that Vergara has managed to parlay what many would see as a deficit – her heavy Spanish accent – into a platform for sharp social critique via the incorrect usage of English-language lexical items. In a subsequent examination of Vergara’s “vocal body,” Dolores Inés Casillas, Juan Sebastían Ferrada and Sara Veronica Hinojos (2018) argue that Vergara-as-Delgado-Pritchett is racialized as a Latina character via her accent. Paying attention to both the visual as well as the sonic markers of Gloria’s Latinidad, they assert that her marked accent and erroneous word choices are deployed for comedic purposes, or to demarcate gender and racial hierarchies. Also citing Vergara’s accent as a primary site of her gendered racialization, Salvador Vidal-Ortiz (2016) ponders whether or not she disrupts any US structures at all, beyond her usage of non-normative English.

Still other scholars, such as Isabel Cristina Porras Contreras, focus on Vergara’s sexuality, noting how the actress, unlike some of the other well-known female “exports” from Colombia, is hailed as an international sex symbol and posited as an exemplar of Latina hypersexuality in the media, whereas the sex workers of her home department in the Colombian Caribbean are widely disparaged and policed.

In the most exhaustive consideration of Vergara’s work in Modern Family to date, Isabel Molina Guzmán (2018) offers a nuanced reading of Gloria Delgado-Pritchett against the backdrop of the “post-racial” United States and what she describes as the tendency towards “hipster racism,” or the US public and media producers’ increased comfort with the deployment of humor and language that could potentially be interpreted as offensive. As Molina-Guzmán contends, television comedies constitute a primary site of hipster racism and colorblindness. This is not because they ignore factors such as race, ethnicity, and gender; rather, programs such as Modern Family deploy sexism, racism, homophobia, and xenophobia in tandem with multicultural representations of racial, gender, and sexual difference as foundational elements of their comedic strategy.

These are some of the contributions of my esteemed colleagues. Their skilled research enhances my thinking about Vergara and her performance of Gloria Delgado-Pritchett, and the dynamics of Latinas in media and popular culture in general.

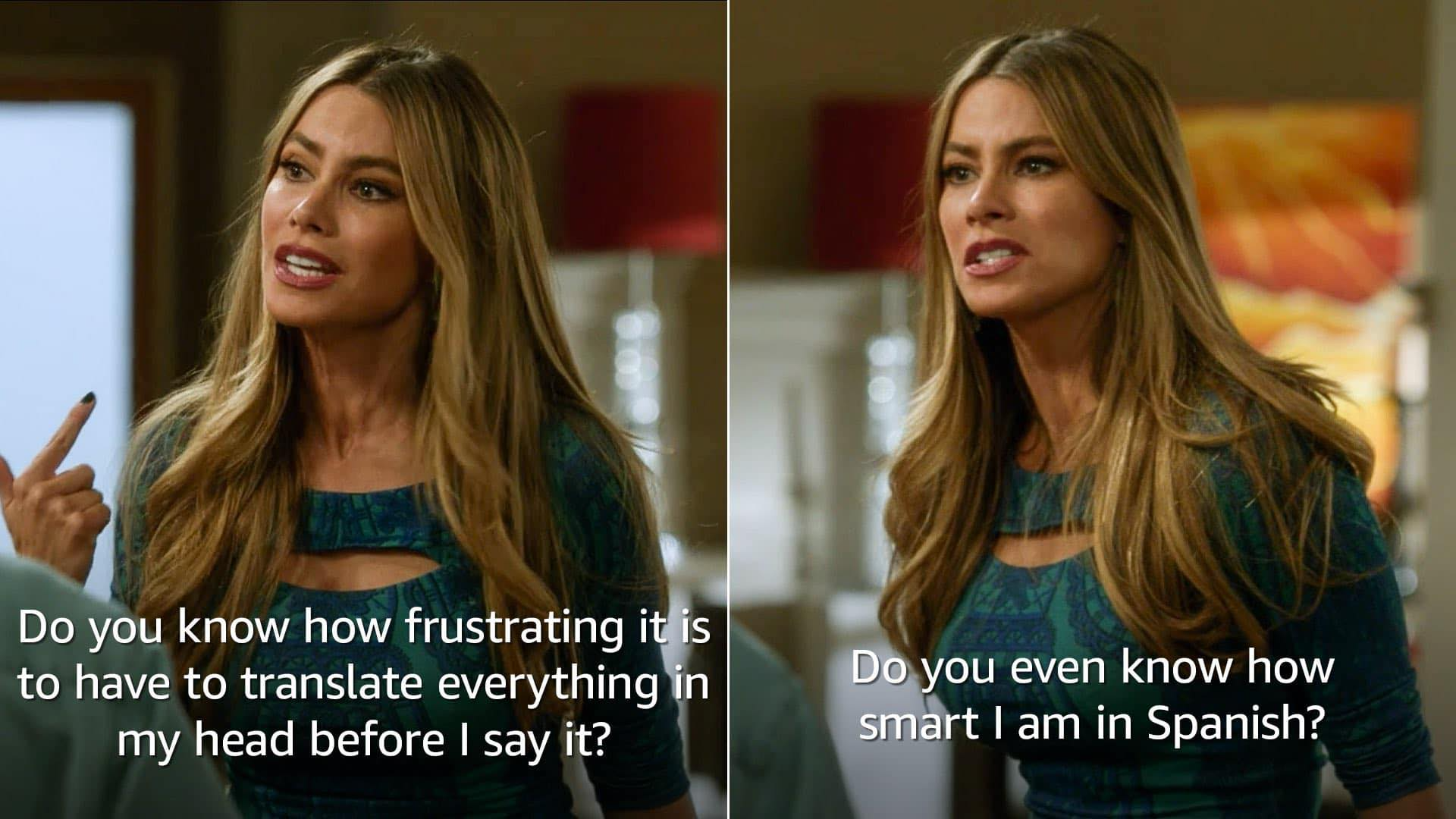

I air this clip in my classes on media and popular culture as a way of illustrating how purposefully embracing Latina/o/x stereotypes in the hopes of drawing attention to their existence may in fact be an effective way of undercutting their power. (Assuming, however, that viewers are in on the “joke” and recognize the artifice of the stereotype as well; this is always a gamble. But when it works, it is a very effective tool for contesting toxic stereotypes). Frances Aparicio and Susana Chávez-Silverman (1997) refer to this as the act of “self” or “re-tropicalization.” The video montage foregrounds Sofía-as-Gloria’s marked accent, her mercurial temper, and her verbal and physical outbursts. The former are frequently delivered directly into the camera in Spanish or Spanglish, regardless of the interlocutor, augmenting the sensation that the performance we are witnessing depicts some sort of raw, unvarnished reality.

Above all, the montage of select moments of Vergara’s performance is punctuated by their reliance on excess: of movement, volume, color, sexuality, as well as emotion – all characteristics historically associated with mainstream representations of Latinas. It is an intricate web of edited clips that draw on the viewer’s familiarity with previous popular depictions of Latina excess, ranging from bygone Spanish star Charo of the 1970s (see Valdivia 2020) to the infamous Lorena Bobbitt of the 1990s. A comment left by “Impossible Lion” on YouTube aptly expresses these contradictory forces at work in Vergara’s performance, noting how for them, Gloria’s appeal is rooted in the fact that she is “funny … yet dangerous at the same time.”

As a US Colombian woman of Vergara’s generation, the daughter of two immigrants from Vergara’s hometown of Barranquilla, and a scholar of Latinas in the media, I would describe my personal reaction to witnessing Vergara play Delgado-Pritchett as similarly conflictive. My reaction is only slightly less emphatic to instances of Sofía Vergara simply “being Sofía” in media interviews. Due to the highly entrenched nature of historic media stereotypes about Latinas – stereotypes which inform the way Sofía-as-Gloria is read by audiences – separating Sofía Vergara the real-life individual from her fictional alter-ego is a particularly fraught task. The undeniable slippages between Vergara’s offscreen star text and her portrayal of Delgado-Pritchett shape the ways in which we interpret her performances of gendered Latinidad. Offscreen and on, Sofía Vergara offers us the Latina we expect, a fact that may be comforting for some in the audience while simultaneously problematic for Latina/o/x viewers in particular. Part of my response to Vergara is grounded in this bitter realization. It provokes in me what can only be described as “vergüenza ajena,” otherwise known in Spanish as “shame-by-proxy.”

From my unique vantage point, seeing and especially hearing Vergara is a vexing experience. It’s like rubbing raw skin – it burns, too tender to the touch. Growing up with a dearth of Latina/o/x media representation, I have always longed to see Colombian women and girls onscreen in the United States (see Cepeda 2020). For me, Vergara as Delgado-Pritchett does not simply revive long-standing media stereotypes about Latinas in general and Colombian women in particular. It is far more complex than that. Rather, her performance of Gloria walks the delicate tightrope between the offensive and the entertaining, and in the process manages to ring very familiar with uncomfortable intimacy. When I hear Sofía-as-Gloria speak in English or Spanish (because the actual Sofía talks quite differently, having attended an elite bilingual school in Barranquilla), when I witness her body language, when I consider the gendered dimensions of her communicative style and the cultural constraints that shape those modes of speaking – even when I fleetingly focus on just those facets of her performance – I recall multiple generations of women in my family and of friends and colleagues from Barranquilla who live in the States: US Colombian women who communicate a particular way as a means of navigating the racism, sexism and xenophobia that they encounter in their daily lives, despite the class and race privileges that some of them also enjoy. US Colombian women who felt intense social pressure to adhere to normative notions of beauty and heterosexual womanhood in Colombia as well as the United States.

I am reminded of myself, of my fraught relationships to Colombian Catholic gender norms in particular, the deeply engrained cultural and religious beliefs about womanhood that travel North with Colombian migrants and that often flourish for generations. I recall the difficult relationships that I often have with my family, conflicts oftentimes grounded in my rejection of the gendered norms with which I was raised.

I realize that this is a dangerous proposition: that the stereotype, the archetype that as a Media Studies scholar and as a Latina I am trained to identify and deconstruct, holds a grain of truth. Let me be clear: I am not arguing that Vergara’s is somehow a more “authentic” or accurate caricature of privileged middle-aged white women from Barranquilla, Colombia. What I do maintain, however, is that in order for scholars to fully examine Sofía Vergara and her work we must account for her Colombian identity. Paying specific attention to Vergara’s Caribbean roots, her gender, her class positionality, her sexualization, and her racial location are particularly necessary to any nuanced analysis of her performance as Gloria.

Upon closer inspection, Sofía Vergara’s portrayal of Gloria Delgado-Pritchett is not a generic Latina performance. Rather, it is a uniquely diasporic, gendered, classed, raced, and regionalized performance that cannot be understood in all of its dimensions without its proper contextualization.

Despite my qualifications, I don’t know if I am capable of this analysis quite yet.

Gloria feels too close.

But I eagerly await it – the moment when she and Sofía start feeling more funny than dangerous.

Image Credits:

- Sofía Vergara “thinking in Spanish” meme

- Sofía Vergara as Gloria Delgado-Pritchett

- Gloria Delgado-Pritchett: The Best of Modern Family

- Gloria in S4 Ep20 “Flip Flop

- Gloria’s Talking Head in S3 Ep5 “Hit and Run”

Aparicio, Frances R., and Susana Chávez-Silverman. 1997. Tropicalizations: Transcultural Representations of Latinidad. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.

Casillas, Dolores Inés, Juan Sebastián Ferrada, and Sara Veronica Hinojos. 2018. “The Accent on Modern Family: Listening to Representations of the Latina Vocal Body.” Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies 43(1): 61-87.

Cepeda, María Elena. 2020. “Latina Feminist Moments of Recognition: Contesting the Boundaries of Gendered US Colombianidad in Bomba Estéreo’s “Soy yo.”” Latino Studies, 8(3): 326-342.

Fernández L’Hoeste, Héctor. 2017. What’s in an Accent: Gender and Cultural Stereotypes in the Work of Sofía Vergara. In The Routledge Companion to Latina/o Media, ed. María Elena Cepeda and Dolores Inés Casillas, 233-240. New York: Routledge.

Molina-Guzmán, Isabel. 2018. Latinas & Latinos on TV: Colorblind Comedy in the Post-Racial Network Era. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Porras-Contreras, Isabel Cristina. 2017. “Sofía Vergara Made Me Do It”: On Beauty, Costeñismo and Transnational Colombian Identity.” In The Routledge Companion to Latina/o Media, ed. María Elena Cepeda and Dolores Inés Casillas, 307-319. New York: Routledge.

Valdivia, Angharad N. 2020. The Gender of Latinidad: Uses and Abuses of Hybridity. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell.

Vidal-Ortiz, Salvador. 2016. “Sofía Vergara: On Media Representations of Latinidad.” In Race and Contention in 21st Century US Media, ed. Jason A. Smith and Bhoomi K. Thakore. 85-99. New York: Routledge.

Your article was enlightening. I also have problems with this character that exploits “Latinity” using the stereotypes and labels US mainstream media culture constructed for consuming Latin American materiality. I understand that Gloria could not represent the whole varied universe of women born in Spanish-speaking countries, but the lack of originality is what makes it uncomfortable.

I agree with you; the lack of originality makes it uncomfortable (for some). And that same lack of originality – which we could also think of as a form of familiarity – guides our interpretations of Vergara’s performance. She gives us the well-worn tropes we expect. Most of us don’t question them because they are rooted in long-standing ideas about Latinas in dominant culture. It’s hard to read those sounds and images of gendered Latinidad in alternative ways but not impossible.