Activism or Performative Activism?: Investigating Jimmy Butler’s “No Name” NBA Jersey

Jas L. Moultrie and Ralina L. Joseph / University of Washington, seattle

The recorded murder in Minneapolis, Minnesota on May 25, 2020 of 46-year-old George Floyd generated an unprecedented global response to Black racialized violence. While the sheer grotesqueness of the 8 minutes and 46 seconds are reason enough for widespread condemnation of anti-Black violence, the physical isolation and virtually simulated connection of #quarantinelife compelled more communities to pay attention. Conscientious media users, even those for whom race had not previously registered as “an issue,” had little room for willful ignorance with everyone indoors and attached to our screens. Before long, brands and corporations began to respond as well.

One of the brands to acknowledge such anti-Black violence was the multi-billion dollar industry of the NBA. For the NBA’s 2019-20 season restart, players could choose from an approved list of 29 social justice slogans to place on their jerseys, including “Black Lives Matter,” “Equality,” “Vote,” “Say Her Name,” and “Education Reform.”

Jimmy Butler, thirty-one year old star of the Miami Heat, wanted to go an entirely different route. He petitioned for anonymity.

“I have decided not to [wear a jersey with a social justice slogan]. With that being said, I hope that my last name doesn’t go on there as well. Just because…I love and respect all the messages the league did choose, but for me, I felt like with no message, with no name, it’s going back to like who I was, and if I wasn’t who I was today. I’m no different from anybody else of color, and I want that to be my message, in the sense that just because I’m an NBA player, everybody has the same rights no matter what. That’s how I feel about my people of color.”[1]

In this conference call with reporters, Butler does his due diligence by giving “love and respect” to the NBA’s version of social justice, but he also resists their version of branding. Butler identifies himself not as an exceptional athlete who might then escape from the forces of anti-Black violence. Instead he firmly names himself as “no name,” “no different from anyone else of color,” and as such, part of a resistance collective who also remains vulnerable to violence. And indeed, Black NBA players have not remained invulnerable to police brutality as the cases of Sterling Brown of the Milwaukee Bucks and Thabo Stefolosha of the Houston Rockets demonstrate.

After submitting his petition, 30 additional players requested to perform nameless. All of their requests were denied. Just before tipoff, however, in an early August game against the Denver Nuggets, Butler decided to wear the anonymous jersey anyway. This act of defiance was quickly quelled as he was made to change in order to play.

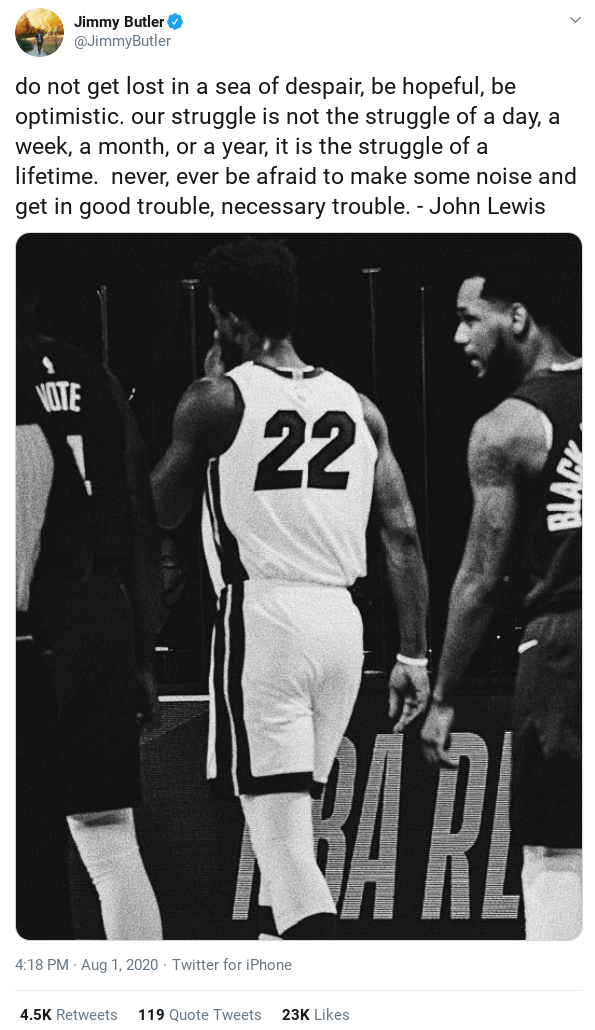

Following the game, Butler posted to his Twitter and Instagram accounts a photo of him wearing the “no name” jersey alongside a quote from recently deceased civil rights leader, John Lewis.

A month later, other NBA players continued to feel the implications of his actions. Jamal Murray of the Denver Nuggets noted,

“Jimmy Butler did one thing, he took his name off of his jersey. I think that was so powerful. Because if he is just another Black man, you wouldn’t be able to tell the difference. Could be homeless, could be walking on the street, you would never know.”[2]

Clearly Butler’s actions have been influential to his fellow players, and a countless number of NBA fans. But were they “activism,” what Cooper et al. conceptualize as the intentional disruption of oppressive systems of power,[3] or “performative activism,” a mere guise of such disruption towards change-making, as defined by critical race scholar and activist, Maia Hoskin?[4] Butler’s identities as a Black man, professional athlete, celebrity influencer, and business owner, among others, speak to his distance from and proximity to power. Such simultaneous distance and proximity complicates our question of “activism” versus “performative activism,” proposing an answer of not either one or the other, but both together, simultaneously.

Minoritized people, or those who are “smaller in power in a racialized economy that systemically denigrates people of color,”[5] challenge opponents through disruption, empowerment, and demands for change. In the sports world, Black athletes resist using raised, black-gloved fists at the podium, linked arms on the field, and dropped knees along the sideline. A legacy of Black athlete activism traces back to the 1900s. Sociologist Harry Edwards locates today’s efforts within a fourth wave of activism that concerns the transference of power.[6] This wave was preceded by eras in which we strove to gain legitimacy (e.g. Jack Johnson), acquire access (e.g. Althea Gibson), and demand dignity, respect, and equal treatment (Muhammad Ali).

Today’s orchestrated, collaborative efforts between sports leagues and athletes feel different from even the fourth wave in which we are purported to be. For instance, further investigation of Butler’s protest revealed the NBA and Heat organizations’ awareness of his plan beforehand thereby allowing, and appropriating, his dissent. Furthermore, while a discussion of differences between activism versus performative activism in the WNBA compared to the NBA are outside the scope of this short column, we do want to note the ways in which the WNBA’s social justice activism, of individuals in concert with the league, illustrates what sports historian Amira Rose Davis calls the WNBA’s “pattern of commitment to social justice.” Because such a pattern has not been long-established in the NBA, the NBA’s league-managed efforts, backed by corporate interests, overshadow impromptu moments of individual resistance. Butler’s attempt at a “no name” jersey versus the NBA-approved social justice jersey messages are but one example.

The approved list of social justice messages was negotiated by the NBA and the players union (NBPA). Interestingly, players could endorse a message on a jersey without their last name, but only for the first four days in the “Bubble.” Players were also limited to choosing from the list. Several, including LeBron James of the Los Angeles Lakers, opted out of the initiative for this very reason, noting:

“I would have loved to have a say-so on what would have went on the back of my jersey. I had a couple things in mind, but I wasn’t part of that process, which is OK…I don’t need to have something on the back of my jersey for people to understand my mission or know what I’m about and what I’m here to do.”[7]

James’s statements critique the performative activism of wearing jerseys alone, and gesture, instead, to his own activism, including his philanthropy through the LeBron James Family Foundation which, for example, opened the “I Promise School,” and his new nonprofit More Than a Vote which donated to the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition in order to allow formerly incarcerated Floridians the right to vote.

Other players, including Tyson Chandler and Austin Rivers, both of the Houston Rockets, wanted to inscribe Trayvon Martin’s name on their jerseys, but were not allowed to. Reportedly, the league and NBPA decided against using the names of victims to forgo the process of obtaining permission from their families and to avoid offending the families of victims not included. Imagine, reading their actual names in place of league-approved “Say Her Name” and “Say Their Names” inscriptions. Explicit, directed attention towards murdered Black people (Trayvon, Tamir, Sandra, Eric, John, Michael, Akai, Walter, Freddie, Atatiana, Korryn) extends their stories and fosters dialogue in a way that would limit the NBA’s control of the narrative.

What also differs in the discursive movement between activism and performative activism is the simultaneous discursive movement from explicit acknowledgement of systemic racism to colorblind and postracial rhetoric. In June 2020, before the season restart, the NBA and NBPA announced their shared goal of addressing systemic racism and racial inequality. Two months later, after the shooting of Jacob Blake and subsequent player labor strikes, the organizations revealed their strategy. In a joint statement, the NBA and NBPA detailed three commitments for the 2019-20 playoff games. These included establishing a social justice coalition, converting team facilities into voting locations, and producing advertisements which promote civic engagement and raise awareness surrounding voter accessibility. The strategy communicated here is voting as the challenge to systemic racism. And while voter suppression is a systemic issue, championing voting initiatives fails to imagine a transference of power, and ultimately shifts responsibility to the individual. Those of us watching at home bear the responsibility instead of the organizations of power (NBA, Turner Broadcasting System, The Walt Disney Company).

Instead of the hyper-visibility of the jerseys, we wonder what might have happened had the NBA and NBPA made their own equity negotiations more visible. We wonder, what if, instead, the NBA had bravely and transparently distributed an audit of their own practices of a more casual form of anti-Black violence that happens through Black exclusion in their own organization? What if they provided data investigating racial disproportionality in all levels of the NBA, not just focusing on players’ jerseys but on the hiring and retention of Black coaches, trainers, front office staff, and even owners? What could fans learn of what disproportionality looks like in terms of recruiting, hiring, mentoring, and promoting Black people internally? Do these numbers approach the proportion of Black players (74.2%)? And if the answer is no, could they share out what is their plan to change their structurally anti-Black practices?

But this didn’t happen. A buried press statement about broad “social justice efforts” and a well-publicized performance of social justice jerseys did. The jersey example of corporate and performative activism represents an unsettling trend. Neoliberal capitalist enterprises are subtly co-opting social justice movements in pursuit of social and financial capital. Termed “cooptations of consciousness,”[8] the people’s pain, anger, and demands for change materialize the sell. Going nameless prevents Jimmy Buckets and the 30 additional players, the ultimate commodities, the NBA’s Black athletes, from being identified, coded, and packaged. Commodified Blackness must be named and marketed to the masses.

Through the lens of the NBA, Black bodies are accepted and validated by their ability to perform, by their entertainment value. Basketball, however, is not the only space through which we are presented as spectacle. The consumption of Black death is a normalized pastime that has been intensified by digital and social media.[9] Through these lenses, unacceptable Black bodies are subject to premature death.[10] In one context, the male Black body is admired, even fetishized. In the other, the same body is vilified and justified as threatening. The case of Jimmy Butler’s jersey activism makes this very paradox of Black masculinity visible.

George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks. These are just some of the victims whose murders occured after the NBA announced it would postpone the season in March. In the aftermath of these hypervisible Black murders, it was necessary for basketball to return. For things to go “back to normal.” White supremacist hegemony depends on its resurrection to balance the spectacle of Black death with Black performance. Examples like Jimmy Butler’s demand for a “no name” jersey complicates this spectacle, combining moments of performative activism with activism.

Image Credits:

- Butler was not allowed to play in a “no name” jersey.

- NBA social justice jerseys.

- Butler removes his “no name” jersey after his request to play nameless is denied.

- Jimmy Butler’s Twitter post following his jersey demonstration.

- Friedell, N. (2020, July 14). Heat’s Jimmy Butler wants no name on back of jersey. ESPN. Retrieved from https://www.espn.com/nba/story/_/id/29461561/heat-jimmy-butler-wants-no-name-back-jersey [↩]

- Youngmisuk, O. (2020, August 29). Nuggets’ Jamal Murray: ‘My skin color should not determine whether I live or die.’ ESPN. Retrieved from https://www.espn.com/nba/story/_/id/29768456/my-skin-color-not-determine-whether-live-die [↩]

- Cooper, J.N., Macaulay, C., & Rodriguez, S.H. (2019). Race and resistance: A typology of African American sport activism. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 54(2), 151–181. [↩]

- Hoskin, M.N. (2020, June 10). Performative activism is the new ‘color-blind’ band-aid for white fragility. Zora. Retrieved from https://zora.medium.com/performative-activism-is-the-new-color-blind-band-aid-for-white-fragility-358e2820a4e1 [↩]

- Joseph, R.L. (2017). What’s the difference with “difference”? Equity, communication, and the politics of difference. International Journal of Communication, 11, 3307. [↩]

- Edwards, H. (2018). Afterword to the 50th anniversary edition. In The revolt of the Black athlete: 50th anniversary edition (157–175). University of Illinois Press. [↩]

- McMenamin, D. (2020, July 11). Lakers’ LeBron James to go without social justice message on jersey. ESPN. Retrieved from https://www.espn.com/nba/story/_/id/29448088/lakers-lebron-james-go-social-justice-message-jersey [↩]

- Moultrie, J.L. (2019). Commodifying consciousness: A visual analysis and discussion on neoliberal multiculturalism in advertising [Master’s thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign]. IDEALS, 61, http://hdl.handle.net/2142/105695 [↩]

- Williams, S. (2016, July 11). Editorial: How does a steady stream of images of Black death affect us. NBC News. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/editorial-how-does-steady-stream-images-black-death-affect-us-n607221 [↩]

- Hong, G. (2015). Death beyond disavowal: The impossible politics of difference. University of Minnesota Press. [↩]

Wow!

This article was amazing and very thought-provoking. I hope that we can continue to provide solutions. The authors write really well and I will continue to read and learn more!