Finding the ‘TV’ in TV News

Deborah L. Jaramillo / Boston University

There’s a classic moment in The Kids in the Hall: Brain Candy (1996) that goes something like this. Grivo, a depressed, chest-baring aggro rocker, looks out onto his audience and softly declares, “I wanna talk about drugs.” A lone voice in the crowd yells, “Heroin!” Grivo replies, “No, not heroin.” “Speed!” the crowd offers. “No, not speed.” Undeterred, the crowd excitedly tries again: “Hashish!” “No, not even hashish.” Stumped, the crowd pauses for a moment and finally asks, “Horse tranquilizers?” “No, not horse tranquilizers.”

This is how I feel about TV news in the academy. Stay with me now.

I, a moody and naturally lethargic TV scholar, say to anyone who will listen, “I wanna talk about TV news.” A loud voice says, “Like journalists do?” No, not like journalists do. Another voice chimes in, “Oh, like in political communication!” No, not like in political communication. “Rhetoric!” No, not even rhetoric. “Media Effects?” No, not media effects.

I wanna talk about TV news as television.

When I began writing my dissertation on cable news war coverage in 2005, I was indebted to the small slice of television scholarship that existed on the subject of news. Not communication scholarship or journalism scholarship, but television scholarship. The work of Margaret Morse showed me there was thoughtful analysis of television news as a genre of storytelling and meaning-making within the culture industries. John Caldwell’s discussion of television news as a vessel for televisuality treated the fusion of style and industry in this neglected genre with great clarity. Thankfully, we have since seen more studies that have analyzed images, sounds, discourse, and industry structure to explain how television news has shaped certain historical moments. And research on television news parodies has reminded us that news is a television genre. Yet, significant gaps remain in our research and in our teaching.

One persistent problem is the vastness and ephemerality of the artifact. Studying TV news is hard because there’s just so much of it, and it’s not meant to be repackaged and rewatched. It’s local, it’s national, it’s all day, it’s everyday. Some is archived (thank you, Texas Archive of the Moving Image), some is not. Where do you start? What is the unit of analysis? To that sense of helplessness, I point to radio scholars who face tremendous odds as they hunt for recordings and scripts. I also point to scholars like Elana Levine who study soap operas with thousands upon thousands of episodes. So, what is the issue, really? Do we really believe it’s not TV? It’s News?

A vast repository of research on television news is available to pick through, but very little of it takes up the concerns of the field of Television Studies. In short, the majority of television news research is on television news—not on television news. I’m not arguing that one approach is superior to the other; I am simply saying that the diversification of research on this topic will similarly diversify the conversation about how the news exists and has existed within the television landscape, with an eye to all of the intersecting axes that concern television scholars.

Now, I’m going to veer into some scholarly territory for a moment, so please bear with me. In a 2018 article, Robinson, Zeng, and Holbert found that while political communication scholarship has de-emphasized the role of television in delivering political information, television remains a dominant source of political news in the face of online and mobile competition (287, 297). Moreover, this dominance is not confined to the U.S.; the authors find that it “transcends national borders and class divisions” (296). In addressing the lack of attention paid to television news by political communication scholars, the authors posit that the prevailing theoretical frameworks used to study political media—“framing, priming, and agenda setting”—are medium agnostic and thus render a medium-specific analysis “unnecessary” (297).

There you go. The dominance of news media analysis informed by these frameworks makes it seem as though (1) these theories hold universal explanatory power; (2) television is interchangeable with any other medium; (3) television is not a complex, historically determined intermixture of technology, industry, culture, stylistic influences, and viewer behaviors; and (4) news is not just one type of television program sitting adjacent to and opposite other types of programs, being influenced by them and competing against them in a landscape shaped by decades-old broadcasting companies, advertisers, and regulations. But here’s another (related) part of the problem. The fields that dominate news research have not excluded others. We just haven’t jumped in with both feet.

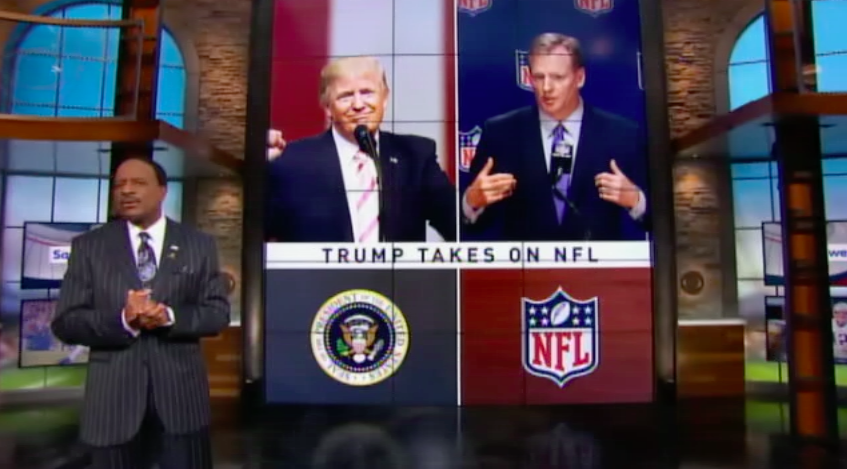

TV Studies is a vibrant field that, for reasons well known to all of us, keeps having to fight for legitimacy in the academy. As we watch scholars from other fields dip into TV, claim the so-called “good” bits for their courses, treat those bits as literature or film, and then get praise in the press for turning TV into something worthy of study, why don’t we make the most of the name of our field and imprint our expertise on all of television? Sports media scholars are the latest to make this case successfully. The recent creation of the Sports Media Scholarly Interest Group at SCMS is an encouraging sign, not just for the study of televised sports, but for the study of the overlap between sports and TV news. Yes, I just inserted myself into their glory, but I do see it as a win for anyone who veers away from the dominant script.

In my remaining columns for Flow I’ll continue to sing this news tune in a few different ways, hopefully offering something positive to the field’s ongoing conversations about how we study TV and why we study it in the ways we do.

Image Credits:

- PBS NEWSHOUR, the nation’s first hour-long nightly news telecast (author’s screengrab)

- All In with Chris Hayes promoting its new Friday live shows on Twitter.

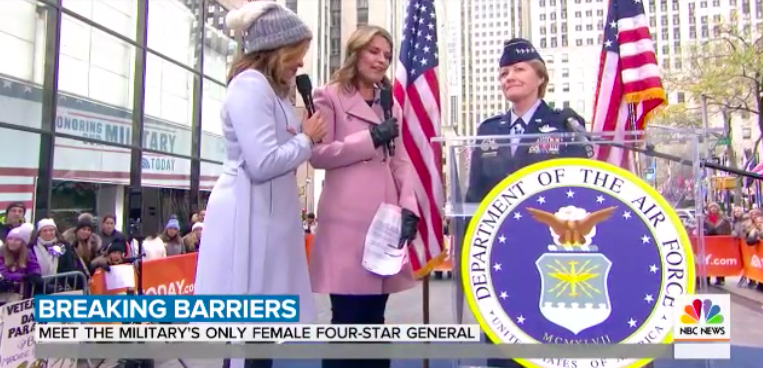

- NBC’s Today, one of the network’s flagship news/talk show programs (author’s screengrab)

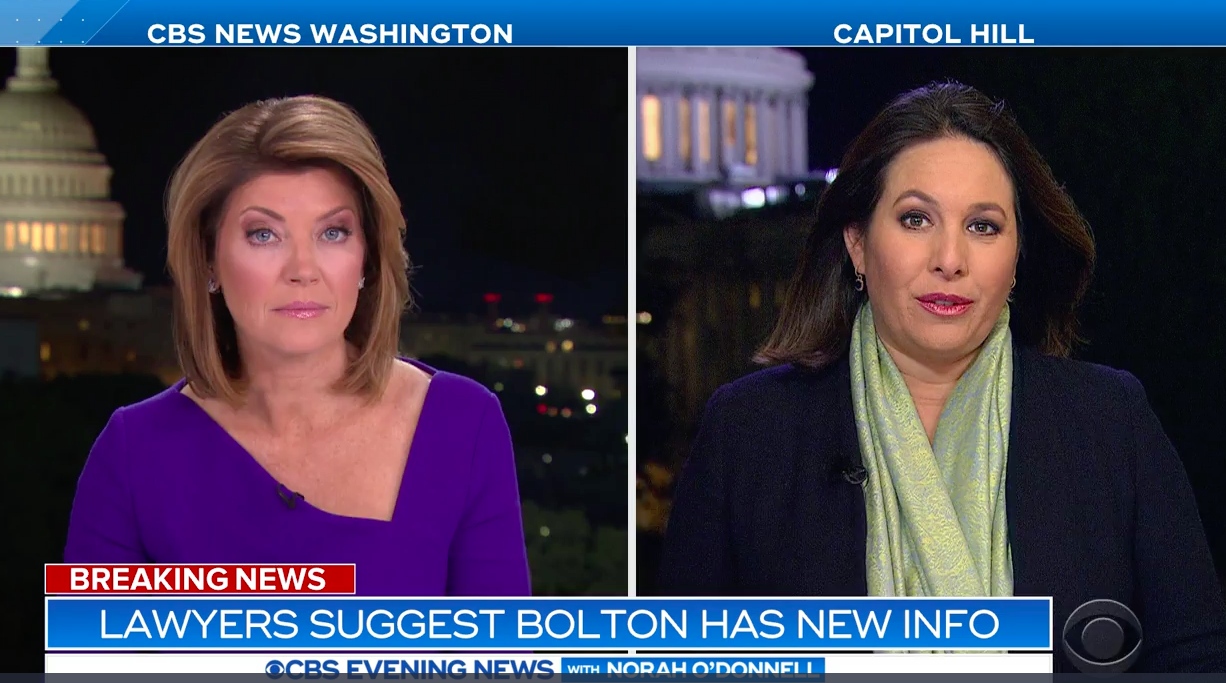

- CBS Evening News with Norah O’Donnell, covering the latest Trump administration news (author’s screengrab)

- The NFL Today on CBS, discussing the president’s comments on NFL stars (author’s screengrab)

Robinson, Nicholas W., Chen Zeng, and R. Lance Holbert. 2018. “The Stubborn Pervasiveness of Television News in the Digital Age and the Field’s Attention to the Medium, 2010-2014.” Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media 62(2): 287-301.

This has been all what we have been needing here.

There you go. The dominance of news media analysis informed by these frameworks makes it seem as though (1) these theories hold universal explanatory power; (2) television is interchangeable with any other medium; (3) television is not a complex, historically determined intermixture of technology, industry, culture, stylistic influences, and viewer behaviors; and (4) news is not just one type of television program sitting adjacent to and opposite other types of programs, being influenced by them and competing against them in a landscape shaped by decades-old broadcasting companies, advertisers, and regulations. But here’s another (related) part of the problem. The fields that dominate news research have not excluded others. We just haven’t jumped in with both feet.