YouTube is Taking K-Pop Global

Patty Ahn / University of California San Diego

YouTube is bringing K-Pop to the U.S. YouTube is taking K-Pop global.

Since 2011, these kinds of celebratory declarations have cycled their way through U.S. and Korean news outlets, research studies, academic essays, and promotional literature released by the Korean government. These stories are almost always buttressed by staggering numerical figures about how many views K-Pop music videos regularly rack up on the site, most of which originate in Japan, China, and the U.S. In August, Sun Lee, head of music partnerships at YouTube for Korea, told Bloomberg, “It might have been impossible for K-pop to have worldwide popularity without YouTube’s global platform.” [1] Views for K-Pop’s Top 200 artists have tripled since 2012, reaching a combined total of 24 billion hits in 2016, 80% of which originated outside of Korea. [2]To be sure, K-Pop’s fan base in the U.S. has expanded considerably over the last five years. This year, KCON, the only major K-Pop fan convention in the U.S., reported its highest attendance record to date, attracting 128,000 total attendees between its Los Angeles and New York events. [3] Much of this growth can be attributed to Korean record labels aggressively and systematically using U.S.-based social networking sites, like Twitter and Instagram, to engage fans in the U.S. and western Europe directly and in a variety of ways. A number of scholars now use expressions like Hallyu 2.0, or K-Pop 2.0, to describe how Korean content providers are using online distribution networks to drive Korea’s “second wave.”

Although YouTube acts as one piece of the Korean music industry’s broader strategy, it plays a crucially important role. For one, it provides record labels with a way to deliver music videos and other visual content to audiences in the U.S. without having to go through traditional media outlets. Korean record labels have known since the late-1990s that their particular style of music video promotion has the power to build strong emotional bonds between audiences and their idols in spite of linguistic and ethnic differences. SM Entertainment—Korea’s oldest and most powerful music firm—is widely credited for establishing the “K-Pop formula” with its first generation of idol groups in the mid-1990s:

(SM Entertainment, 1996)

SM’s founder, Lee Soo Man, has said that he modeled the company’s visually-driven approach to musical promotion after Michael Jackson, who displayed his virtuosity as a singer and dancer through high-concept music videos. Lee saw how Jackson reshaped the American entertainment industry while living in the States in the early 1980s, and wanted to reproduce that kind of entertainment to appeal to Korea’s bourgeoning youth culture in the mid-1990s. [4] SM developed a company-wide system in which potential idols were recruited based on physical appearance, trained as dancers, vocalists and media personalities, and then aggressively promoted through music videos and televised performances. SM soon learned that the synchronized dance routines, pastel sounds and boyish energy of its idol groups were also captivating young audiences in Singapore, Hong Kong, mainland China, Taiwan, the Philippines and Indonesia. Long before YouTube arrived, regional and satellite networks and local television networks were broadcasting music videos and entertainment programs licensed from Korea.

Chinese-language media coined the term K-Pop to describe this emerging fan base in the late 1990s. It did not take long before the Korean music industry and government assimilated the term into a broader strategy to globalize the “made-in-Korea” brand. In 2009, Korea’s three largest record labels—SM, YG Entertainment, and JYP Entertainment—worked with YouTube to take their visual strategy online. Their incentives for partnering with Google’s video sharing platform were especially high. Between 2006 and 2008, each label ran a failed campaign to bring their top grossing solo artist in Asia to the American market. As for why these campaigns failed, we need only remember the racialized account music critic Jon Pareles gave in The New York Times about Rain’s foray into U.S. music—the JYP Asian mega-star did not meet the American standards of masculinity or originality. [5]

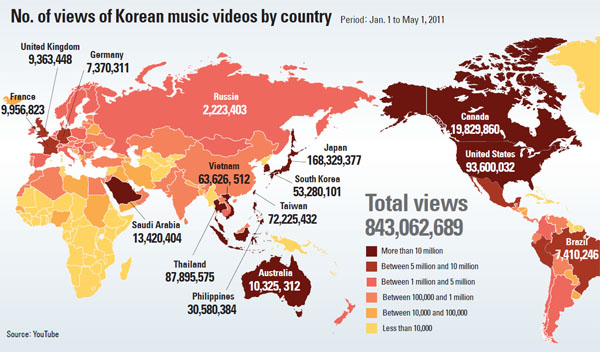

That narrative changed in early 2011 when YouTube began releasing metrics that showed how K-Pop idol groups were tracking on its site. The company published several visualizations of these metrics in the form of color-coded maps, which were then circulated to the public through Korean fan sites [6], newspapers [7], and research journals. [8] They all revealed that the U.S. accounted for the heaviest concentration of views outside of Asia. A representative from Google Korea declared, “The year 2011 was the first year when K-Pop really established itself as a global trend, instead of a temporary fad. In 2012, K-Pop will continue to grow its influence around the world.” [9]

“Point choreography”—the use of key movements to capture the audience’s attention in a song—has served as a crucially important visual strategy for expanding into non-Asian markets. When executed successfully, point choreography will act as a visual hook, almost like an ear worm that conjures to mind a visual movement repeated in the chorus—a perfect ingredient for virality. SM’s nine-member girl group Girls’ Generation proved the point with their music video, “Gee.”

(SM Entertainment, 2009)

The chorus is driven by a simple, repetitive chant of the song’s title, “Gee, Gee, Gee, Baby Baby” as all nine members perform a tightly synchronized dance routine of geometric movements performed in perfect unison. The main dance number in “Gee” inspired fans to upload videos of their own dance covers and flash mobs organized en masse across Asia, the U.S., and even Paris, France.

K-Pop’s hallmarks as a genre are now defined as much by its spellbinding group choreographies as its heart-pounding beats and melodic hooks:

(NegaNetwork, 2010)

(YG Entertainment 2013)

(YG Entertainment 2013)

Metrics and virality only tell one piece of the story. The hundreds of K-Pop videos being shared and re-shared billions of times per year, and recreated in virtual and public space, more than anything creates a architecture of global sound and gendered fantasy, one which captures a feeling or imagined space of a post-millennial Korea.

Image Credits

1. YouTube Map

2. “Abracadabra”

3. “Gentleman”

4. “TT”

Please feel free to comment.

- Sohee Kim, “The $4.7 Billion K-Pop Industry Chases Its ‘Michael Jackson Moment,’” Bloomberg, August 22, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-08-22/the-4-7-billion-k-pop-industry-chases-its-michael-jackson-moment. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Jeff Benjamin, “KCON 2017 Breaks Attendance Records Thanks to Seventeen, GOT7, VIXX, Super Junior-D&E, Cosmic Girls & More,” Fuse, August 22, 2017, https://www.fuse.tv/2017/08/kcon-2017-la-attendance-recap. [↩]

- Lie, John, and Ingyu Oh. “SM Entertainment and Soo Man Lee.” In Handbook of East Asian Entrepreneurship, edited by Fu-Lai Yu and Ho-Don Yan, 346–52. New York, New York: Routledge, 2015. [↩]

- Jon Pareles, “Korean Superstar Who Smiles and Says, ‘I’m Lonely,’” The New York Times, February 4, 2006, sec. Arts / Music, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/02/04/arts/music/04rain.html. [↩]

- thunderstix, “K-Pop Videos Set New Record on YouTube,” Soompi (blog), January 2, 2012, http://www.soompi.com/2012/01/02/kpop-videos-set-new-record-on-youtube/. [↩]

- “Web Triggers Global Renaissance of Korean Wave,” Korea JoongAng Daily, September 15, 2011, http://mengnews.joins.com/view.aspx?aId=2941492. [↩]

- Min-Soo Seo, “Lessons from K-Pop’s Global Success,” SERI Quarterly 5, no. 3 (July 2012): 60–66,9. [↩]

- thunderstix, “K-Pop Videos Set New Record on YouTube,” Soompi (blog), January 2, 2012, http://www.soompi.com/2012/01/02/kpop-videos-set-new-record-on-youtube/. [↩]

In 2014, South Korea topped the annual EU Innovation Index. The “Made-in-Korea” pop culture has become the main economic innovation in the country. In addition to the U.S. based platform like YouTube, some indigenous social media in Asian countries has also become a strategy to globalize k-pop band. The fan base is mainly from young generation. Which means that traditional forms of media, such as radio, television, and newspaper play a less significant role in the promotion and globalization of k-pop, compared with YouTube that is more accessible, subjective, and youthful. The failed campaign of Rain’s foray into the American market mentioned in the article represents the gendered fantasy of Asian phenomena. Especially when Korean entertainment companies systematically take physical appearance as their top consideration, the cross-cultural variability in attractiveness may become a barrier to promote an idol in a country with different sociocultural perspectives. However, there are several successful cases worth to mention. BTS, a seven-member South Korea boy band, won Billboard Music Awards in 2017, thanks to billion views on their videos posted on their official YouTube channel.

From the gifs and music videos presented in this article, I found that the virality of K-Pop’s music videos is quite fascinating. As a K-Pop fan for many years, I think the music genre’s evolution and its means of dissemination closely follow the characteristics of the digital age. Instead of merely emphasizing the artistic and auditory effects of music, K-Pop has experienced the transition and transformation from the aural experience to audio-visual experience, from “listening to music” to “looking at music”. These kinds of adjustment were made based on realistic conditions of fragmentation of information and the shortened patience of audiences in the digital age, which requires visual impact and strong rhythmic dance and melody that can instantly capture the attention of the audience. In addition, the traditional storytelling is often played down in K-Pop music videos, replaced by group dances, brilliant colors, and rapid switching of individual and group shots to form a rhythmic visual impact that not only makes up for the lack of narratives, but also creates a gorgeous and spectacular stage effect with the powerful combination of images.

Pingback: K-pop and Globalization – Field Research Final – English 210 – Writing for the Social Sciences

I am liking this approach from Youtube. I have been watching Burning The Stage from BTS on Youtube and I am greatly enjoying the series. Looking at how hard these boys work make me love them even more.

Pingback: How International Artists Took Pop Music’s Center Stage In 2020 - GoneTrending