The Allusions of Television

My colleagues (I teach in an English Department), convinced television is a sinister force destined to destroy literacy and dumb down culture and appalled at my traitorous introduction of its study into hallowed halls that once echoed with the language of Chaucer, Shakespeare, Keats, Conrad, and Faulkner, were not amused when I suggested we tout our rich-in-popular culture course offerings in new promos, updating the old curricular formula, inviting study of “Beowulf to Buffy (and Virginia Woolf, Too).” Not convinced by recent arguments to the contrary like Steven Johnson’s Everything Bad is Good for You: How Today’s Popular Culture is Actually Making Us Smarter, television’s antagonists, in their ignorance, would have us believe the “vast wasteland” offers nothing (with the exception of an occasional Masterpiece Theatre) to the literary minded.

Though I am under no illusion they will listen, allow me to survey contemporary television in search of but one manifestation of the literariness the rabid book-loving-TV-haters imagine absent from the medium: the allusion. Allusions, of course, are direct or indirect references in a work of art, usually “without explicit identification, to a person, place or event” or to another work (Abrams 8). Wherever they appear, allusions are, of course, part of that vast and intricate system of intertextuality carefully examined in Jonathan Gray’s recent book. Allusions are not, of course, limited to the literary, even though they carry with them, because of their bookish past, a kind of literary cache.

It would, of course, be easy to find in the wasteland allusions to other inhabitants of the wasteland. When Ed Hurley and Agent Cooper visit One-Eyed Jacks in Twin Peaks using the aliases of Barney and Fred, the teleliterate (Bianculli) picking up on a reference to The Flintstones is much easier than understanding the series’ vatic mysteries. When, on Lost, a British businessman buys the Slough branch of the Wernham Hogg paper company, we may not immediately recognize the momentary diegetic intersection with the BBC’s The Office, but the allusionary crossing is there to follow nonetheless. I want to examine here not television’s incestuous televisual allusions but its literary ones. For with surprising regularity, the wasteland invokes not just Eliot’s “Wasteland” (Wilcox) but the whole world of literature to which it remains a seldom respected heir.

First, consider series like Seinfeld (NBC, 1989-1998), Twin Peaks (ABC, 1990-1992), and Buffy the Vampire Slayer (WB, 1997-2001; UPN, 2001-2003)–all series famous for being rife with popular culture references. “It’s so sad. All of your knowledge of high culture comes from Bugs Bunny Cartoons,” Elaine laments to Jerry in the Season Four Seinfeld episode “The Opera,” but the series itself exhibits more than a cartoony awareness of the literary, giving us references to Death of a Salesman (Jerry repeatedly refers to George as “Biff”), The Great Gatsby, Moby-Dick, Salman Rushdie, Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn, and Tolstoy and War and Peace.

Twin Peaks hardly limited itself to movie, television, and music references, though full of them. Remember that discussion of the Heisenberg indeterminancy principle at the Double R Diner? By the series’ premature end, the attentive Peaker had no doubt noticed that Edmond Spenser’s Fairie Queene (Windom Earle and Leo Johnson’s “verdant bower”), the Arthurian legends (Glastonbury Grove, King Arthur’s burial site, is home to the Black Lodge as well), and Knut Hamsun (the Nobel-Prize winning Norwegian novelist and fascist, much admired by Ben Horne), have all set up housekeeping in Twin Peaks.

In seven seasons under the creative control of fanboy/comic book geek/pop culture genius Joss Whedon, Buffy the Vampire Slayer was crammed with references to television, comics, film, music, and literature. The poetry of Robert Frost, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and Emily Dickinson; a plethora of books and writers–Alice in Wonderland, The Call of the Wild, Brave New World, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, William Burroughs, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, Of Human Bondage, Heart of Darkness, C. S. Forester, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Vanity Fair, The Open Road, Where the Wild Things Are, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Ann Rice; and a variety of plays–Oedipus Rex (hilariously performed in a talent show in Season One), The Merchant of Venice, Othello, Waiting for Godot, Death of a Salesman (a dream version with a cowboy and a vampire), all these and more put in cameo appearances in Sunnydale. In Buffy’s most extraordinary allusional moment, in the astonishing “Restless,” an episode made of four dream sequences, Willow inscribes Sappho’s lesbian poem “Mighty Aphrodite” on her lover Tara’s naked back.

Not surprisingly, the Buffy spinoff Angel makes abundant use of literary allusions as well. I will limit myself here to only one. In a Season One episode the series’ titular hero, an over-two-centuries-old vampire, is forced to briefly masquerade as a docent in an art museum. Luckily he has personal knowledge of the painting before which he stands

The Cast of Angel

[Angel speaking] “And this brings us to Manet’s incomparable La Musique Aux Tuileries, first exhibited in 1863. On the left one spies the painter himself. In the middle distance is the French poet and critic Baudelaire, a friend of the artist. Now, Baudelaire…interesting fellow. In his poem ‘Le Vampyre’ he wrote: ‘Thou who abruptly as a knife didst come into my heart.’ He, ah, strongly believed that evil forces surrounded mankind. And some even speculated that the poem was about a real vampire. (He laughs). Oh and, ah, Baudelaire’s actually a little taller and a lot drunker than he’s depicted here.”

Perhaps the first mention on television of the French symbolist poet and drug enthusiast, but then again Angel may well have been the first television character who knew Baudelaire personally.

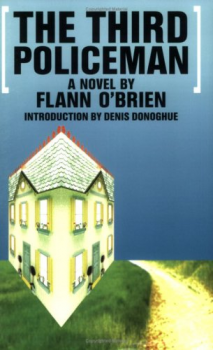

Third Policeman

Literary allusions crashed on mystery island along with the survivors of Oceanic 815 in ABC’s huge international hit Lost. Not only are well known philosophers–England’s John Locke and France’s Jean-Jacques Rousseau–evoked by character names, several books become images in the frame, including Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw, Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman, Madeline L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time, and Richard Adams’ Watership Down, and still others–Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, James Hilton’s Lost Horizon,and Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe–are clearly brought to mind.

Since, until recently, television routinely kept its episode titles to itself, it has been easy to miss the many literary references to be found there, then and now. Consider, for example, the final episode of the short-lived but watershed ABC series My So Called Life (1994) entitled “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities”–a somewhat obscure allusion to a book of the same name by the American poet and writer Delmore Schwartz; or the Steinbeck-evoking pun in the title of an upcoming Veronica Mars episode “The Rapes of Graff” (compare to The Simpsons‘ “The Crepes of Wrath”); or The Gilmore Girls‘ “Say Goodbye to Daisy Miller,” with its reference to the Henry James novella (one of a score of literary show titles in the series); or “The Betrayal,” Seinfeld‘s famous “backward” episode, which takes its title from Nobel Laureate Harold Pinter’s similarly-themed (though opposite in tone) play of the same name.

Taking great pride, and capitalizing on a great branding opportunity, in being “not TV,” HBO programs are just as rich in literary allusions as in nudity and vulgarity. Not surprisingly, Deadwood, created by former Yale University English professor David Milch and written in a language indebted to both Shakespeare and the Victorian novel, offers many a literary reference (did Alma Garrett just compare Miss Isringhausen to Cotton Mather?).

But it is on HBO’s flagship series The Sopranos, where the literary allusions by far outnumber the whacks, the wiretaps, and the lapdances, that the not-TV allusions find their true home. (The following catalog is limited to Seasons Four and Five only.) Mr. Wexler explains to Carmela that A. J. has turned in a “surprisingly cogent” draft on George Orwell’s fable Animal Farm. With Rosie Aprile’s depression in mind, Janice laments “Ah, Bartleby. Ah, humanity,” quoting the final lines of Melville’s novella. Another Melville novella puts in an appearance when A. J. has to write a paper on “Billy Budd,” an assignment which leads to a later discussion (evoking the iconoclastic critic Leslie Fiedler) about its possible gay subtext. (His next reading assignment is Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice.) Meadow tells her mother she read “half the canon” while lying by the pool. Tony B. confesses to Christopher that “some very sorry people” once called him Ichabod Crane (the main character in Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”). New York underboss Johnny Sack cites Shakespeare’s Macbeth–“creeps in this petty pace”–in complaining about his long wait for the overboss to die. In after-extra-marital sex pillow talk, Mr. Wexler tells Carmela Soprano about Heloise and Abelard, after she finds their letters as reading material in the English teacher’s bathroom. One of Tony’s captains speaks enviously of the earning potential of the Harry Potter books. Ready to embark on a trip to Europe, Meadow recommends her parents read Henry James in order to learn more about “the restorative nature of travel.” A. J. buys a paper on Lord of the Flies on the Internet. Carmela reads Flaubert’s Madame Bovary. Melfi quotes Yeats’ poem “The Second Coming” to an uncomprehending Tony. A fifth season episode takes its title from Flaubert’s A Sentimental Education.

From Northern Exposure

And of course we cannot neglect CBS’ Northern Exposure (1900-1995), which might well have been the most literary program in the history of medium (Lavery, “Deconstruction at Bat”). On Northern Exposure, Franz Kafka once paid a visit to Cicely, Alaska, an elderly store owner reads Dante, an entire episode replicates Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, and the overflowing-with-literary allusions local DJ reads Walt Whitman and War and Peace on the morning show and infuses his banter with references to Kierkegaard, Kant, Nietzsche, de Tocqueville, and Jung (to name only a few) like they’re old friends. The episode “The Graduate,” in which Chris must defend his M.A. thesis, a deconstructionist reading of “Casey at the Bat,” even gives us a spirited debate over post-structuralist literary theory.

Allusions, the great literary scholar M. H. Abrams observes, “imply a fund of knowledge that is shared by an author and an audience. Most literary allusions are intended to be recognized by the generally educated readers of the author’s time,” though some have always been “aimed at a special coterie” and, in modernist literature, may be so specialized that only scholarly annotators will be able to decipher them (8-9). TV’s allusions likewise imply a mutual “fund of knowledge.” When they are merely to the rest of the vast cosmos of television, as they often are, they presume nothing more than the commonality of many hours before the small screen. But television’s proliferating literary references stand as a testimony to the medium’s increasing sophistication as its begins to partake in “the conversation of mankind” (Rorty), to the wider, deeper repertoire of its writers, and to new, much more flattering, assumptions about the intellectual qualities of the Quality TV audience. If some of the allusions of television are now so arcane only English professors can elucidate them, well do we not need new challenges, new work to do?

Works Cited

Abrams, M. H. A Glossary of Literary Terms. 5th ed. NY: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1970.

Bianculli, David. Teleliteracy: Taking Television Seriously. The Television Series. Syracuse: Syracuse UP, 2000.

Gray, Jonathan. Watching with The Simpsons: Television, Parody, and Interextuality. New York: Routledge, 2005.

Johnson, Steven. Everything Bad is Good for You: How Today’s Popular Culture is Actually Making Us Smarter. New York: Riverhead, 2005.

Lavery, David. “Appendix B: Intertextual Moments and Allusions in Seasons Four and Five.” Reading The Sopranos: Hit TV from HBO. London: I. B. Tauris, 2006. 217-32.

—. “Appendix C: Intertextual Moments and Allusions in The Sopranos.” This Thing of Ours: Investigating The Sopranos. Ed. David Lavery. New York: Columbia UP, 2002. 235-53.

—. “Deconstruction at Bat: Baseball vs. Critical Theory in Northern Exposure’s ‘The Graduate.'” Forthcoming in Critical Studies in Television, Vol. 1, No. 2.

Rorty, Richard. Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1981.

Wilcox, Rhonda V. “T. S. Eliot Comes to Television: ‘Restless.'” Why Buffy Matters: The Art of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. London: I. B. Tauris, 2005. 162-73.

Image Credits:

Please feel free to comment.

Manet vs. Buffy

This article raises issues that have continually come up when I teach, during sections where we discuss what if any borders may exist between modernist and postmodernist techniques for re-presenting works from the past in present cultural production (especially TV–where this is especially pronounced). One of the many issues that comes up is the question of “cultural knowledge,” in that many will say that postmodernist intertextuality requires no special education, but rather “only” a cultural literacy that requires little effort on the part of the viewer for comprehension. My students continually argue that the texts they enjoy are universal, based on how easy it is for them to understand them without special preparation (i.e. what students consider “elite” or “high art” knowledge). The problems with this perspective are numerous. As cultural theorists have shown, texts that drew on “cultural knowledge” in the past and required “only” cultural literacy for their audiences (say those at Shakespeare’s plays during his time) now require texts and scholars to explain the depth and significance of cultural references–or else they are lost to people from other cultures and times. Is that not going to be the case for The Simpsons, or my students’ favorite, The Family Guy? Is not our sense of postmodernism and “easy accessibility” a lot more contingent (and even “Western”) than we often give it credit? In the future, having the cultural preparation to enjoy Manet may not be any less elite than having the formation to enjoy Buffy.

Shakespeare vs. Stewie

Jean’s right in claiming that understanding shows like The Simpsons and The Family Guy demand a strong cultural literacy that often goes unrecognized by students (and scholars) because they don’t appreciate just how immersed they are in the cultural mediascape(s) in which these references readily circulate.

Using The Family Guy as an example, one can easily imagine the difficulty explaining Adam West’s role as Quahog’s Mayor, the Kool-Aid Guy’s busting down the family’s living room wall, or Brian’s attempt at cheering up Peter by doing the “It’s Peanut Butter Jelly Time” dance (referencing the animated web meme from a few years ago) to one not familiar with the original texts.

Now arguably these two animated series in particular cash in on more TV, film, and new media allusions than most televised fare. However, just because they don’t exclusively or principally reference classic literature doesn’t mean that linking these allusions to their source materials is a far cry from the mental gymnastics needed for grounding “high art” references.

And although I’m not familiar with the particular goings-on common to English/Classic Literature departments, the anxieties expressed by Lavery’s colleagues probably mirror other departmental turf-wars over opening their own canonical gates to popular culture. For instance, I’m thinking here of literacy education’s reluctance to introduce moving images to the curriculum, and the challenges faced by film studies 30+ years ago; which, BTW, looks a lot like today’s game studies/ludology debates.

But instead of framing TV as posing a number of educational challenges (e.g., TV as institutional threat; TV as moral panic; TV as low art; TV as undifferentiated mass), could it not be framed as a treasure-trove of scholastic opportunities (e.g., TV as institutional expansion; TV as cultural performance/critique; TV as celebrating and expanding canons of English lit and myth; TV as unique and derivative narratives)? You know, along the lines of “When the Lord gives you lemons, you make lemonade” … and then parlay it into a lemonade stand that can be packaged and sold to Bravo as a cutting-edge reality series (think, The Real World meets The Apprentice meets lemon juice).

And though some in Higher Ed might try to forget TV, TV clearly has not forgotten Higher Ed – English/Film studies courses are playfully mocked in both The Simpsons (where they study an Itchy & Scratchy cartoon) and in The Family Guy (where a futuristic college class studies The Family Guy for artistic merit).

But perhaps it is Stewie – the megalomaniacal, homicidal, erudite, and effeminate toddler from The Family Guy – who best vioces our snarky misgivings about valuing televisual allusions:

Olivia: You are the weakest link, goodbye.

Stewie: Oh gosh that’s funny! That’s really funny! Do you write your own material? Do you? Because that is so fresh. You are the weakest link goodbye. You know, I’ve, I’ve never heard anyone make that joke before. Hmm. You’re the first. I’ve never heard anyone reference, reference that outside the program before. Because that’s what she says on the show right? Isn’t it? You are the weakest link goodbye. And, and yet you’ve taken that and used it out of context to insult me in this everyday situation. God what a clever, smart girl you must be, to come up with a joke like that all by yourself. That’s so fresh too. Any, any Titanic jokes you want to throw at me too as long as we’re hitting these phenomena at the height of their popularity. God you’re so funny.

Research Query

Dear David:Hello.

My name is Ben. I am doing research on pop culture, specifically The Dukes of Hazzard. I am hopeful you can provide me with some information because of your expertise.

1. Why did it attract viewers?

2. Does it promote more family values or rebellion against authority?

3. Does Smokey and the Bandit deserve credit for the popularity?

4. Could you direct me to sources useful to my study?

Thank you for your time.

Dear David:I was just about to start writing an article on this same subject when I read yours. It was much better than mine could ever be! Congratulations on a cogent argument!

A couple of additonal points: while young pop culture enthusiasts who watch Family Guy and Buffy, etc., might not understand many of the literary allusions, I believe the references might work much like adult content works now in children’s movies. The movie can be viewed on more than one level, but as the children grow up they also grow interested in the allusions they once did not understand, and take the trouble to research them. I know many who watched Buffy who dedicated themselves to searching out its references.

Television grows ever more complex, and as it does, it is interesting to see how movies begin to pale in comparison. The best HBO episodes or even CSI, Law and Order, Missing, Grey’s Anatomy, to name just a few, are far superior to ninety-nine percent of the movies now being shown. It’s almost as if the movies are simplifying at the same time that television is adding new layers of complexity and richness for its viewer’s edification and pleasure.

What bugs me about this argument is that it weighs to heavily on the conventional notion that the book is a more intellectual medium to begin with. The whole argument is way to broad and it becomes about mediums not enough about content and usage. The fact that you point out that Tv makes more and more literary references doesn’t prove that TV is intellectual, instead it just re-asserts the notion that the book is a priori more intellectual.

yo thanx man i been tryin to find sh*t about the bible and family guy for my english thing

I think it’s funny that right after he said he worked in the English Department he made a grammatical mistake… They ARE convinced. Just sayin’ :)

Hey shortstuff…you are the one in error. There’s nothing wrong with the grammar…its called nested clauses. Try to follow along with the punctuation. If you going to try to find fault, keep your critique to content because you clearly don’t qualify for the grammar police. Yeah, so…right back at ya…just sayin’

@Don…you make a good point in your argument about media vs. content and usage. Critical studies cannot reliable compare the content of books to the content of television without first understanding the role of television as a mode of literacy and how it informs and is informed by society.

Television as a literary medium is just now entering a zone of more serious inquiry in terms of both its content and as a legitimate cultural platform of literacy. I think that is the reason why critics tend to make so many references to book-based allusions that appear in television content when discussing the merits of of new media as a critical cultural “literature.” However, I don’t think that necessary implies that books are inherently more intellectual, it’s just that books have a well-established canon from which to draw when doing a comparative study.