Kids and Cable: Teaching Regulatory Circumvention

Kit Hughes / Colorado State University

Controversy over television violence’s impact on children seems quaint—a relic of a pre-internet age when the broadcast networks dominated discussion of the mediated public sphere. And yet, the effects of these discussions remain crucial for understanding far more than whether watching Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (syndication, 1987-90; CBS, 1990-96) turned me, a civilian in the culture wars of the 80s and 90s, into an antisocial weirdo.

The advocacy and legislative work that positioned quality children’s programming as a public good paved the way for the cable industry to position itself as a public service leader in the 1990s—at the very the same time cable pushed to maintain the deregulatory/anti-equity environment fostered by Ronald Reagan’s FCC appointee Mark Fowler.

The Failures of Broadcasting

If we look at the primary targets of pressure groups and federal legislation from the 1970s to the 1990s, the debate over children’s television seems confined to the networks. Responding to longstanding fears over TV violence and its effects, the Surgeon General’s 1972 study of television violence focused the attention of disparate groups that found common cause in reforming the content of what the industry called “Kidvid.” Whether pushing against ads during children’s programming (Action for Children’s Television) or fighting indecency and the existence of gay and lesbian people on television (Parents Television Council, the Coalition for Better Television), Kidvid campaigns gained wide press attention for their sponsor boycotts and calls for broadcaster self-regulation.[1]

Legislatively, one of the key victories of children’s television advocates was the Children’s Television Act of 1990 (CTA), which asserted for the record that licensees “should provide programming that serves the special needs of children” as part of their public service duties. The CTA required stations to limit commercials during kids’ shows and established a (short-lived) fund to provide grants for quality educational programming (the rather ambitiously titled National Endowment for Children’s Educational Television). The final provision of CTA was the “consideration of children’s television service in broadcast license renewal.” While refraining from mandating a specific amount of children’s television (in its early years), the Act suggested that quality children’s programming would factor in to the license renewal process.

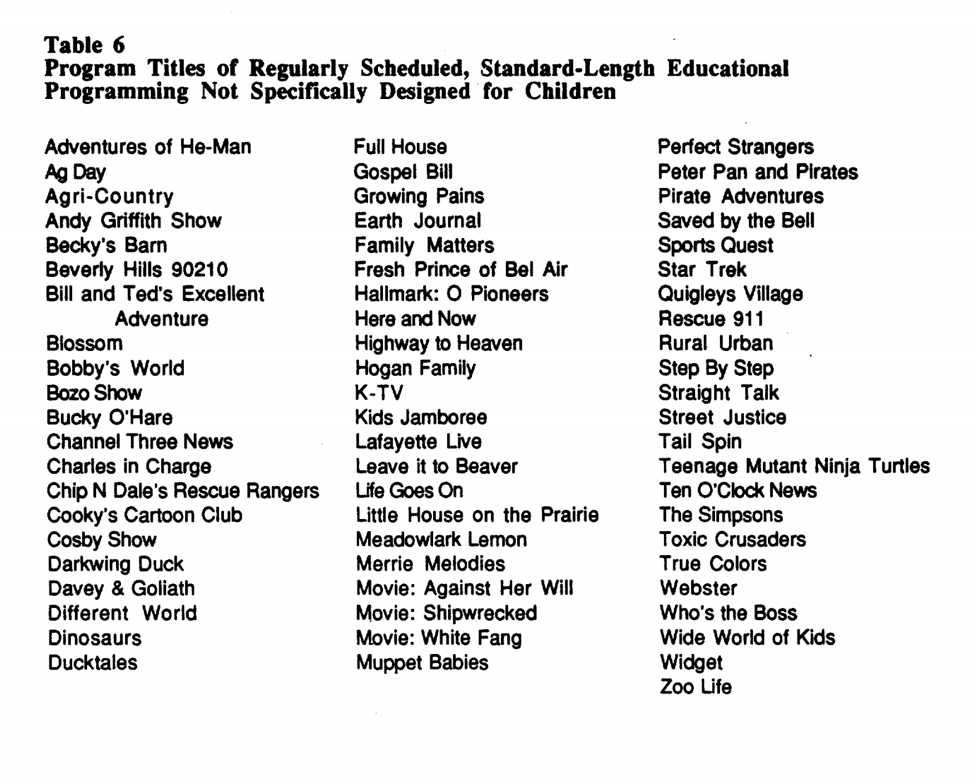

Broadcasters’ unwillingness to comply to the spirit of the law resulted in licensees’ acrobatic refashioning of the purpose and content of their existing programming. Suddenly, according to broadcaster’s license renewal applications, Yogi Bear (syndicated, 1961-62) teaches kids not to steal, the Flintstones (ABC, 1960-66) teaches history, and Biker Mice from Mars (syndicated, 1993-96) teaches caring for others (after all, the Biker Mice routinely defend their home planet from destructive invaders). Following the CTA’s impact provides entertaining reading; the obvious subterfuge of licensees made for good copy in extensive news coverage criticizing the excesses of television (see below for more). Indeed, the early failure of the Act to compel quality television was more of a story than the act itself, transforming broadcasting into an ideal foil for cable’s Kidvid campaigns.

Ultimately, while it concerned the television content of my own youth, I’m not terribly interested in material changes made (or not) to Kidvid in the 1980s and 1990s. Instead, I want to begin to trace how these large-scale debates over broadcast children’s television provided the ground on which the cable industry staged a bid to become the public interest standard-bearer in the same period it pushed vigorously for deregulation.

And Cable’s Response

In short, I argue that children’s “quality” television was the ideal public interest issue for an industry that built its appeal to consumers on programming distinction while pitching narrowcast audiences to advertisers. But how did the cable industry mobilize these fundamental characteristics of U.S. cable in public campaigns?

One initiative of the National Cable Television Association (NCTA)—the industry’s major trade association—was the National Television Violence Study (NTVS). A 3-year, 4-university project commencing in 1993, the NTVS performed an extensive content analysis of broadcast and cable programming to track violence on television and explore its potential effects on children. Underwritten by NCTA to the tune of $3 million, the study provided the cable industry a mechanism to respond to increasing public anxiety over television violence (legislators introduced seven different proposals to curb television violence in 1993 alone) without directly threatening programmers’ use of edgier content to attract subscribers.

I certainly don’t disparage either the quality of work or sincere dedication of the researchers involved in the study, which was undertaken independently of NCTA. However, I do suggest that NCTA likely saw a “violence and children’s television” study as an ideal mechanism to showcase cable’s “public interest” value relative to the broadcast networks. As a function of narrowcasting and a larger stable of national programming distributors, cable boasted C-SPAN, Nickelodeon, A&E, and CNN (among others). Despite its share of programming violence, cable was always going to look good in comparison to broadcast television when it came to children-specific programming. Indeed, yet another study from 1993, the Violence Index compiled by George Gerbner and others, indicated there was “substantially less” violence in children’s programming on cable—though cable hosted more violence overall.[2]

All of this talk of television violence—and quality cable television—supported the NCTA’s second major “public service” offering, Cable in the Classroom. Founded in 1989 amid growing public dissatisfaction with the impacts of the deregulatory 1984 Cable Act, CIC allowed educators to tape commercial-free programming aired before the regular programming day freed of copyright claims.

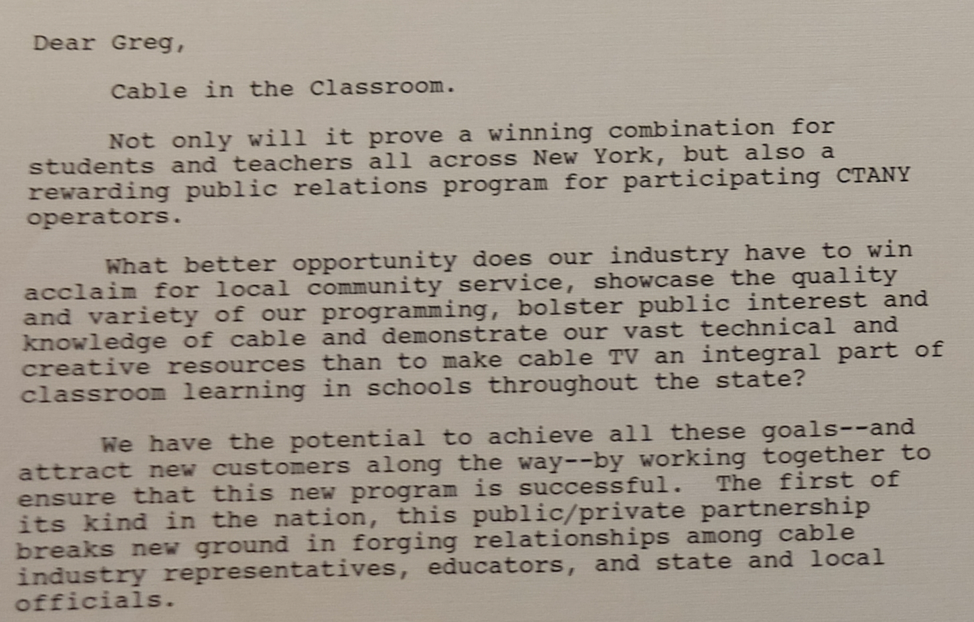

CIC provided the cable industry with a means to offload their own “public service” onto schools. There, critiques of cable’s handling of violence and discrimination could be addressed through educational programming for middle and high school students, rather than structural changes in ownership or greater franchisee investment in in public access, educational, and government channels. As the president of the New York Cable Association put it in a letter to Jones Intercable:

The stakes of CIC—which extend beyond increased control of media infrastructure—coincide with those I discussed in my previous column. Despite lacking the overt commercialization of Channel One, CIC (which continued until 2014) nevertheless helped redefine educational television as the province of private media companies. Here, yet another bit of context is crucial: the same pro-corporate austerity administration that passed the deregulatory 1984 Cable Act also starved public schools of funding, leading to a widely-covered “crisis” in education. CIC, a public-private partnership, was perfectly pitched to solve a crisis with the seeds of its own making (a state that takes money from public coffers to subsidize private business interests). Old hat by now, the idea that businesses should have any say in the process of education has been repeated so many times that watching some nationally-distributed A&E documentary on the space race seems rather benign compared to charter schools, careerism in higher ed, and for-profit universities. However, like the friendly “Market Commentary” and NYSE films of last time, these initiatives fit capital’s attempts to cloak itself as disinterested teacher. Whether to develop our faculties to serve the interests of financialization or to short-circuit regulatory attempts to create a more equitable media landscape, this is not education for the public interest.

Image Credits:

- Promotional guide produced by the cable industry to promote their quality kids’ programming. CC75 folder 6. The Cable Center, Denver, CO. (Author’s personal collection)

- All of the above programs were cited by at least one broadcaster as part of their “educational” offerings during license renewal. While researching policy can be dry, one way to work against the tedium in this case is to play “what educational value, this?” Perfect Strangers (how to engage cultural differences), Beverly Hills 90210 (class inequality), Ten O’Clock News (if it bleeds, it leads).

- Letter to Greg Liptak, May 25, 1990. CC124, Box 4, folder 30. The Cable Center, Denver, CO. (Author’s personal collection)

- For thorough analysis of these campaigns, which often differed in their aims and strategy, see Heather Hendershot, Saturday Morning Censors: Television Regulation before the V-Chip (Durham: Duke University Press, 1999), especially chapters 1-3 and Allison Perlman, Public Interests: Media Advocacy and Struggles over U.S. Television (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2016): 123-150. [↩]

- These studies were routinely invoked in popular and academic discussions of television violence. See, for example, Stephen J. Kim’s “‘Viewer Discretion Is Advised’: A Structural Approach to the Issue of Television Violence,” Pennsylvania Law Review 142, no 4 (1994): 1383-1441, which also gives a nice overview of the legislative activity surrounding the issue of television violence. [↩]