The Gamification of Television? Bandersnatch, Video Games, and Human-Machine Interaction

Ryan Stoldt / The University of Iowa

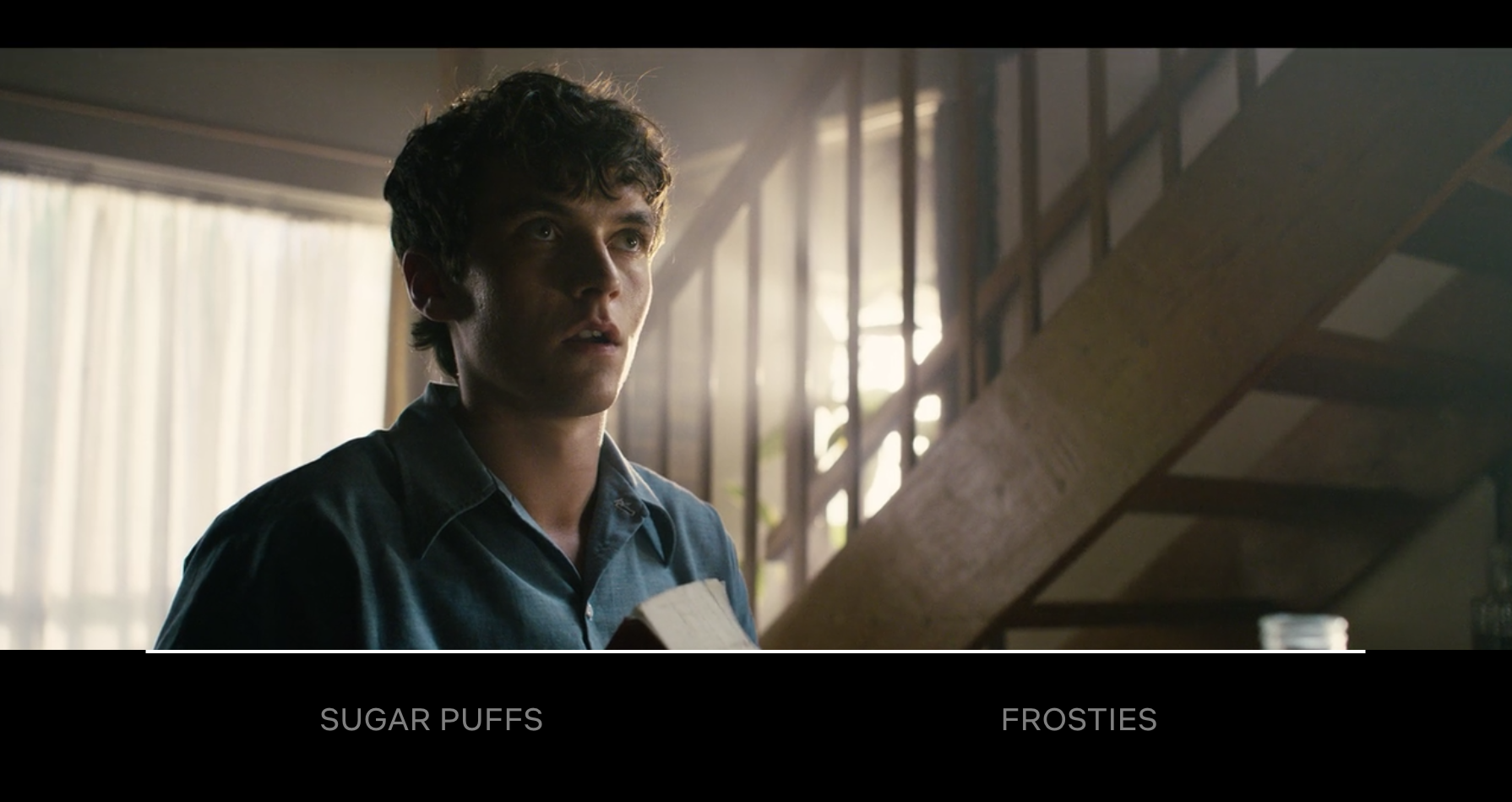

Netflix’s Black Mirror: Bandersnatch (2018) follows Stefan Butler (Fionn Whitehead) as he attempts to create a choose-your-own-adventure video game, in which “choices come up on the screen and you pick one against the clock.”[1] This fictional video game, also entitled Bandersnatch, serves as a meta-commentary for the format of the television episode, which allows audiences to interact with the episode by choosing between binary options that result in narrative variations. Through this meta-comparison of the episodic format to the narrative world’s video game, Black Mirror: Bandersnatch argues for the gamic nature of interactive television and raises direct opportunities for the episode to be compared to modern video games like Supermassive Games’ Until Dawn (2015), which similarly employs branching choice narratives.

As the narratives, technology, and personnel involved in the creation of interactive television and video games converge, media scholars need to continue noting formal differences that affect the types of engagement offered to audiences by different delivery technologies. Although tempting to equate interactive television and video games, this column highlights how interactive television functions similarly and differently than video games, ultimately speaking to the different types of engagement each medium offers.

Television studies is intricately linked to the active audience theory of media, which states that audiences are not passive media consumers but actively make meaning from media messages through their social contexts. As television becomes more interactive, the theoretical approaches scholars use to make sense of the medium need to expand. Digital media scholar Alexander Galloway argues that interactive media moves beyond active audience theory because the physical actions of the user affect the material of the interactive medium itself.[2] While bodies may respond to media messages in active audience theory, they do not intercede in how narratives progress or how machines input and output information. Black Mirror: Bandersnatch and other forms of interactive television ask audiences to bring their body into the narrative by physically engaging with the story by scrolling between choices and pressing buttons. Galloway’s inclusion of both the narrative and the machine in his conception of interactivity provides a useful distinction from other types of physical interactions audiences have with television—such as audiences using their phones to vote in reality television competitions like American Idol (Fox, 2002-2016 and ABC, 2018–) and the physical acts involved in turning on and off technology. From this perspective, interactive television is defined through the relationship between human and machine actions which cooperatively generate a narrative.

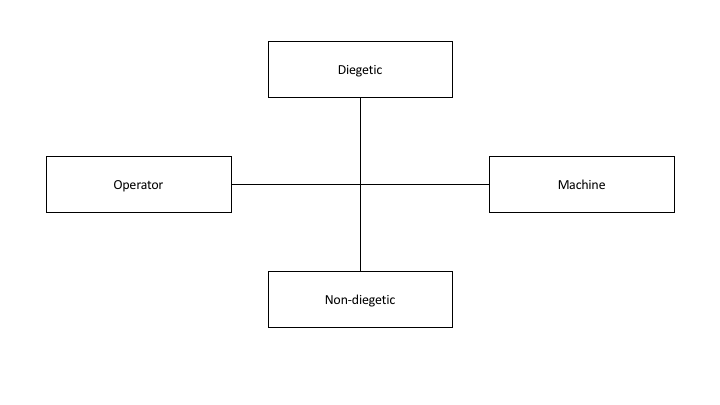

While Galloway’s conception of interactivity provides a useful analysis of how interactive television theoretically functions differently from past engagements with television, it does not fully provide a way of distinguishing between interactive television and video games. To help accomplish this, Galloway’s typology of four gamic moments further breaks down the interactions between humans and machines. These moments span across two axes: diegetic/non-diegetic, or whether the action is taking place inside the story or outside the narrative world; and human/machine, whether the actions are being generated by the input of the user or the machine. By using this typology to compare Black Mirror: Bandersnatch and a video game built around similar player choices like Until Dawn, these gamic moments help distinguish what each medium offers audiences in terms of engagement.[3]

Galloway’s first gamic moment is the diegetic-operator action.[4] This moment occurs in a video game when the player directly interacts with the world of the story and prompts machinic reactions. Video games have a long history of varied diegetic operator acts, like the ability for players to control how playable characters move, interact with, and see the gamic world. Until Dawn offers players the ability to freely move their characters around the world and engage with the world based on a limited number of preset choices. These actions create branches of machinic reactions that shape which narrative is told in the game. Black Mirror: Bandersnatch offers operators a similar type of expression through its use of binary choices to trigger which narrative will play next. Although they offer a drastically different number of diegetic operator acts, this gamic moment functions similarly in interactive television and video games.

Operators are not just constrained to actions that take place within the narrative world though. Galloway’s second gamic moment is the non-diegetic operator act, which focuses on operator actions that take place outside of the narrative world but still function as play. These moments are built around operator actions involving information and configuration. Once again, interactive television and video games share basic similarities in this moment, like the pause button and the ability to toggle the usage of captions with audio. Video games typically offer more non-diegetic operator actions through their pause menus than interactive television. Until Dawn offers players a variety of menu options when paused, like the ability to see stats about the relationship levels between characters in game and look at collectible items from the story.

The two previously mentioned moments focus on how the operator acts on the machine. Galloway argues that machines also act on players though. The third gamic moment, non-diegetic machine acts, occurs similarly in video games and interactive television. These moments take place outside of the narrative world but occur within the machine. Lag, crashes, and other machinic errors may occur regardless of medium and function as disabling acts.[5]

Galloway’s final gamic moment, diegetic machine acts, take place in the narrative world through pure machinic process, meaning the machine acts without input from an operator. This moment encompasses a range of actions common in video games, like the ambient acts of the non-playable characters, the game world, and playable characters that are not receiving operator input as well as cutscenes that continue unaffected by operator actions.[6] For instance, if a person walks away from Until Dawn without pausing, the character continues to exist in a moving narrative world in a moment of machinic ambience. This type of ambient action does not exist in interactive television because, to date, television streaming technology does not algorithmically generate content. It streams the pre-recorded footage available within the database. While moments of ambience denote one area where interactive television and video games differ, the machinic deployment of cutscenes truly highlights the need to understand interactive television and video games differently.

Cutscenes occur at the intersection of player input and machinic response. The cutscene itself is a diegetic machine act, but the trigger is a diegetic operator act. However, the interaction between human and machine does not need to occur for cutscenes to play in Black Mirror: Bandersnatch. Netflix will automatically play the next scene whether or not a viewer interacts with a choice. Because of this, current forms of interactive television can be consumed without interaction between human and machine, where audiences engage with the program actively instead of interactively. This denotes a key difference between video games and interactive television currently—to consume a narrative, video games require interactions between humans and machines while interactive television provides the option for interaction without the necessity.

While interactive television and video games share many of Galloway’s gamic moments, the moments they do not fully share, mainly the relationship between diegetic machine and operator acts, highlight the importance of distinguishing how the formal elements of different media can result in different types of audience engagement. Interactive television like Black Mirror: Bandersnatch allows audiences to consume stories either actively or interactively, a choice unavailable in video games. Active audience theory applies to both groups, but the narratives that active and interactive consumers see will likely differ based on their level of engagement. More interactive audiences have a broader range of possible narrative outcomes, which also broadens the number of potential ideological interpretations a text may provide.

Image Credits:

- Netflix’s Black Mirror: Bandersnatch offers viewers interactivity through binary choices that affect the narrative they’ll see. (author’s screen grab)

- Branching choice narratives in video games like Until Dawn offer players similar choices to the binary options available to viewers of Black Mirror: Bandersnatch. (author’s screen grab)

- Not only are technology and narratives converging across media. Personnel are also appearing across media. Rami Malek and Hayden Panettiere both act as playable characters in Until Dawn.

- Galloway’s four moments on gamic action are broken up along two axes. (author’s image; adaptation of Galloway’s quadrants of four gamic moments)

- Black Mirror: Bandersnatch, directed by David Slade. (London: Netflix, 2018). [↩]

- Alexander R. Galloway, Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004) 3. [↩]

- Galloway, Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture, 17. [↩]

- Galloway, Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture, 17. [↩]

- Galloway, Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture, 3. [↩]

- Galloway, Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture, 10. [↩]

Would you know of a cloned interactive game where stolen images are used for “movies” or videos. I “might” be a victim of this type game. Any info much appreciated.

Game was used to monitor people – even those that didn’t sign up for the game. It used used highly questionable technologies to monitor its “players” / victims.

Would you know of a cloned interactive game where stolen images are used for “movies” or videos. I “might” be a victim of this type game. Any info much appreciated.

This game might be sending bots to computers here at the library.