Mapping Situated Practice from an Insider’s Perspective

Josephine Coleman / Brunel University

When I began my doctoral research exploring how community radio practitioners make programmes by sourcing, shaping and sharing content on-air and online, I already had decades of experience as a radio producer/presenter and volunteer. It made sense to research a field that I was passionate about. I decided to apply Theodore Schatzki’s framework conceptualising practitioner knowledge, know-how, and arrays of tasks as ‘social sites’ of practice. For Schatzki, a practice is situated in time and space, influenced by a web of understandings and conventions, relationships, emotions and expectations interlinked with access to the appropriate tools and equipment (Schatzki, 2002, 2017). In my data gathering, then, I needed to get as close as possible to my research participants.

I realised that although my prior knowledge would be useful in planning and implementing my research, it might also bring certain presumptions and pre-conceived ideas to my work. I needed to avoid any bias influencing my findings and analysis, so I needed to conduct on-site (in-situ) participant observation whilst remaining as objective as possible. This conscious attempt at objectivity met head on with acknowledging my subjectivity, something which French philosopher, Pierre Bourdieu, advises on brilliantly: researchers must recognise their own social capital and privilege when working in the field with human subjects (Bourdieu, 2004).

As I discuss elsewhere (Coleman, 2020a), when researching creative or professional practice such as journalism from the perspective of a practitioner, it is important to recognise, acknowledge and analyse the extent to which capital such as privilege and access – or the lack of those advantages – may impact your own performance as well as influence your attitudes towards the performances of other people. This approach provides deeper insights into the inner workings of a particular field and how external factors influence it. By virtue of your subjectivity, you are better positioned to enact an emic exploration, enabling you to recognise the nuances of others’ behaviour and interactions that can inform your later theorising.

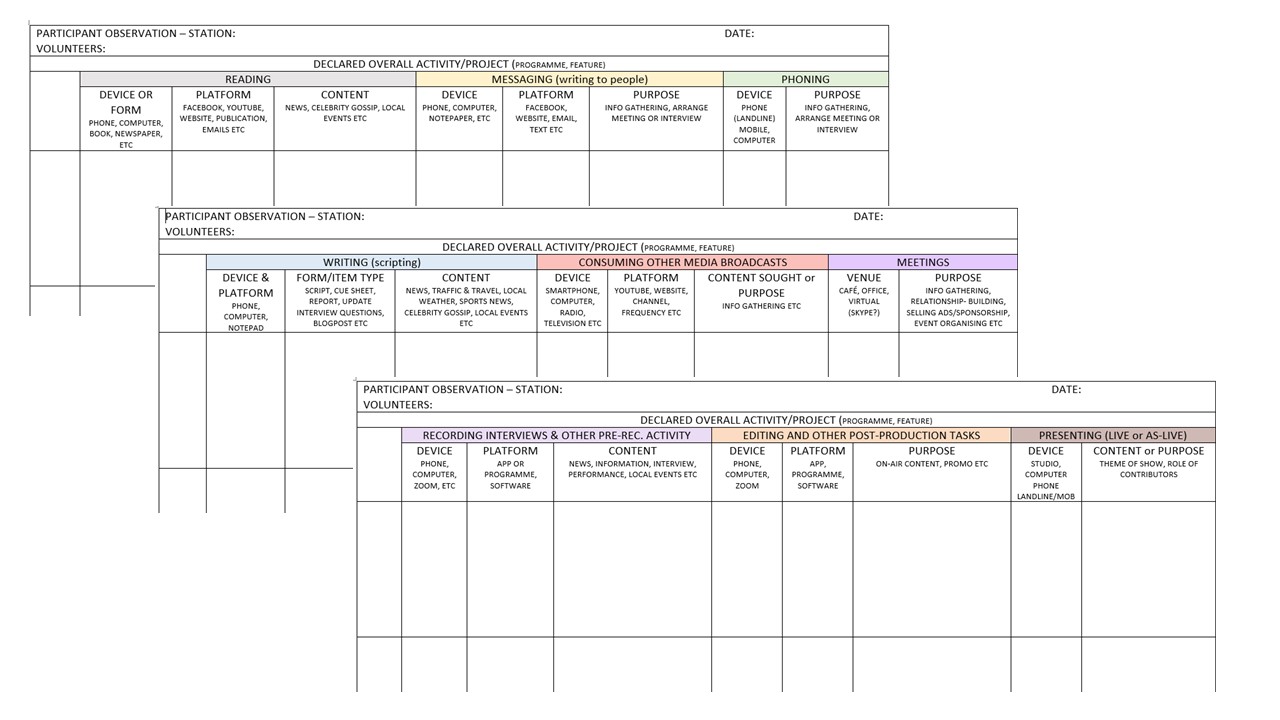

As the Observational Forms above illustrate, using insider experience to frame the parameters of an observational study can provide valuable insights. Your findings will be fine-grained and contextualised because the subjective emic perspective is also ‘situated’ in particular places. To do this well requires relationship-building and collaboration. In a research situation, your presence impacts upon the people you are researching. They may be inhibited by you watching actions which they usually perform unthinkingly, out of habit. The observed subject (research participant) may become more self-conscious, aware that an academic is interested in what they do, how they do it and why. Things are pointed out or ideas are prompted by our questions further spurring the practitioners to reflect on the exchanges and appreciate differently their role and the conditions within which they operate.

So, when we wish to observe people doing things, even though we aim to be objective and non-invasive, we must earn their trust, enabling us to inhabit that shared space. We should reassure them that despite closely watching their activities, how they use technology and other assets, registering their moods and motivations, our intention is not to be judgmental. What we discover can, hopefully, be of use for improving and enhancing their practitioner experience and the conditions in which they operate.

As researchers, we make a commitment to our research participants. Ethnographic-type research is often long-term; it involves accessing social sites of practice, witnessing privileged insider goings-on, gaining insights by engaging with people to experience the emotional and affective immersion in their environment. We can then contextualise or ‘map’ their everyday practitioner lives. As ethnographer Sarah Pink explains:

Mapping flattens things, mapping takes a slide of the world from above … moving through enables us to actually understand live as it progresses through the paths that life takes … how it meanders through environments.

Pink, 2018, interview video podcast, at circa 13’15”

Thus, situatedness is key to providing informed understandings of the way people live in the world around them, the relationships that matter, and which material things and immaterial aspects in the structures and systems they rely on in order to navigate their everyday practices (Pink, 2008).

When the pandemic struck, I wanted to research how operations within UK community radio stations were impacted (Coleman, 2020b). Of course, this work had to be done remotely because in-situ participant observation was rendered unviable due to lockdown and other restrictions. I substituted meeting interviewees face-to-face with telephone and video calls and circulating digital questionnaires. I used alternative ways of encountering my research participants to explore their practice performances. Techniques of digital ethnography including listening to their outputs, scrolling through station archives and other published media coverage, covert lurking on social media platforms and overt participation in online communities, became pivotal. I was able to reach a good number of practitioners, received a statistically-relevant sample of responses, and was able to describe in some detail how the sector was coping based on individual cases and to draw together some recommendations for achieving sustainability of service (Coleman, 2021).

I enjoyed doing the research that way from the comfort of my own home office; it felt efficient, better for the planet (in terms of carbon footprint), relatively easy and safe. However, I was not physically there to observe how the subjects actually did things. Relying on their reports of behaviour and conditions meant that I missed the opportunity to notice aspects of their practice which were second nature to them, as well as any recent shifts which they may have assumed were insignificant.

Applying ethnographic research methods online

If you search a library for resources on ‘digital ethnography’, you will find multiple texts explaining the application of this research method to online platforms, where material and digital lives are entwined (Pink et al., 2016).

It depends on what you are studying and the nature of the material you hope to find that determines how embedded you ought to be. For instance, Helen Burrows conducts her research on fandom remotely. She studies the socio-cultural influence on audiences of The Archers: a long-running, farming-based soap opera on BBC Radio Four (Burrows, 2023). For Burrows, since the fans have created their own groups using social media, situating her research across the digital platforms where interactions take place makes sense. She does, however, acknowledge the

[l]imitations inherent in participant observation, not least in terms of objectivity and replicability … Fan groups are self-selecting and may not fully reflect the identity of the wider listener population. Significant demographics may be excluded, as online groups rely on technological literacy and accessibility (Burrows, 2023).

Burrows, 2023

So, let’s not fool ourselves into believing that online research equips us to identify and uncover every nuance of practice and performance in remote situations. Digital ethnography techniques came in especially useful during the pandemic, when social and professional lives migrated onto online platforms, and have since become instilled in our toolkit. We can reach much further afield, as if the boundaries of time and space can be overcome. However, if we are not there in person to hear and see for ourselves how research participants perform in response to their local environments, we must accept that our experience of their behaviour will be limited. If we are not immersed in the same surroundings or ambience of the performances that we are mapping, can we fully make sense of the subtlety of what we are observing?

Image Credits:

- Image 1: The Researcher reporting at Harpenden Xmas Lights in November 2017. (Author’s personal collection.)

- Image 2: The Researcher’s Observational Forms for PhD research. (Author’s personal collection.)

- Image 3: Participant observation at The Eye in 2018. (Author’s personal collection.)

Bourdieu, P. (2004) Science of science and reflexivity. USA: University of Chicago Press. Available at: http://www.press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/S/bo3630402.html (Accessed: 3 August 2017).

Burrows, H. (2023) ‘Radio Fandom and Informal Education – The Archers as a case study’, Journal of Radio & Audio Media 30:2 pp. 481-495

Coleman, J.F. (2020a) ‘Situating journalistic coverage: a practice theory approach to researching local community radio production in the United Kingdom’, in A. Gulyas and D. Baines (eds) The Routledge companion to local media and journalism. 1st edn. Routledge (Routledge Media and Cultural Studies Companions), pp. 343–353.

Coleman, J.F. (2020b) UK community radio production responses to COVID-19. London: Brunel University. Available at: http://bura.brunel.ac.uk/handle/2438/21156.

Coleman, J.F. (2021) ‘Strength in numbers: The challenges of running community radio in the United Kingdom’, Interactions: Studies in Communication & Culture. Intellect. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1386/iscc_00039_1.

Pink, S. (2008) ‘An urban tour: the sensory sociality of ethnographic place-making’, Ethnography, 9(2), pp. 175–196. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138108089467.

Pink, S. et al. (2016) Digital ethnography: principles and practice. Los Angeles: SAGE (Book, Whole). Available at: https://go.exlibris.link/rjQ448G4.

Pink, S. interviewed by Thore Husfeldt (2018) https://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=digital+ethnography&docid=603526841669911204&mid=86E65DC100096870AFFD86E65DC100096870AFFD&view=detail&FORM=VIRE accessed August 15th 2023 – IT University of Copenhagen, February 26th 2018

Schatzki, T.R. (2002) The site of the social: a philosophical account of the constitution of social life and change. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. Schatzki, T.R. (2017) ‘Sayings, texts and discursive formations’, in A. Hui, T.R. Schatzki, and E. Shove (eds) The nexus of practices. London; New York: Routledge, pp. 126–140.