The Global Local: Geographies of Regional American Film Nonprofits

Hannah Wold / University of Texas at Austin

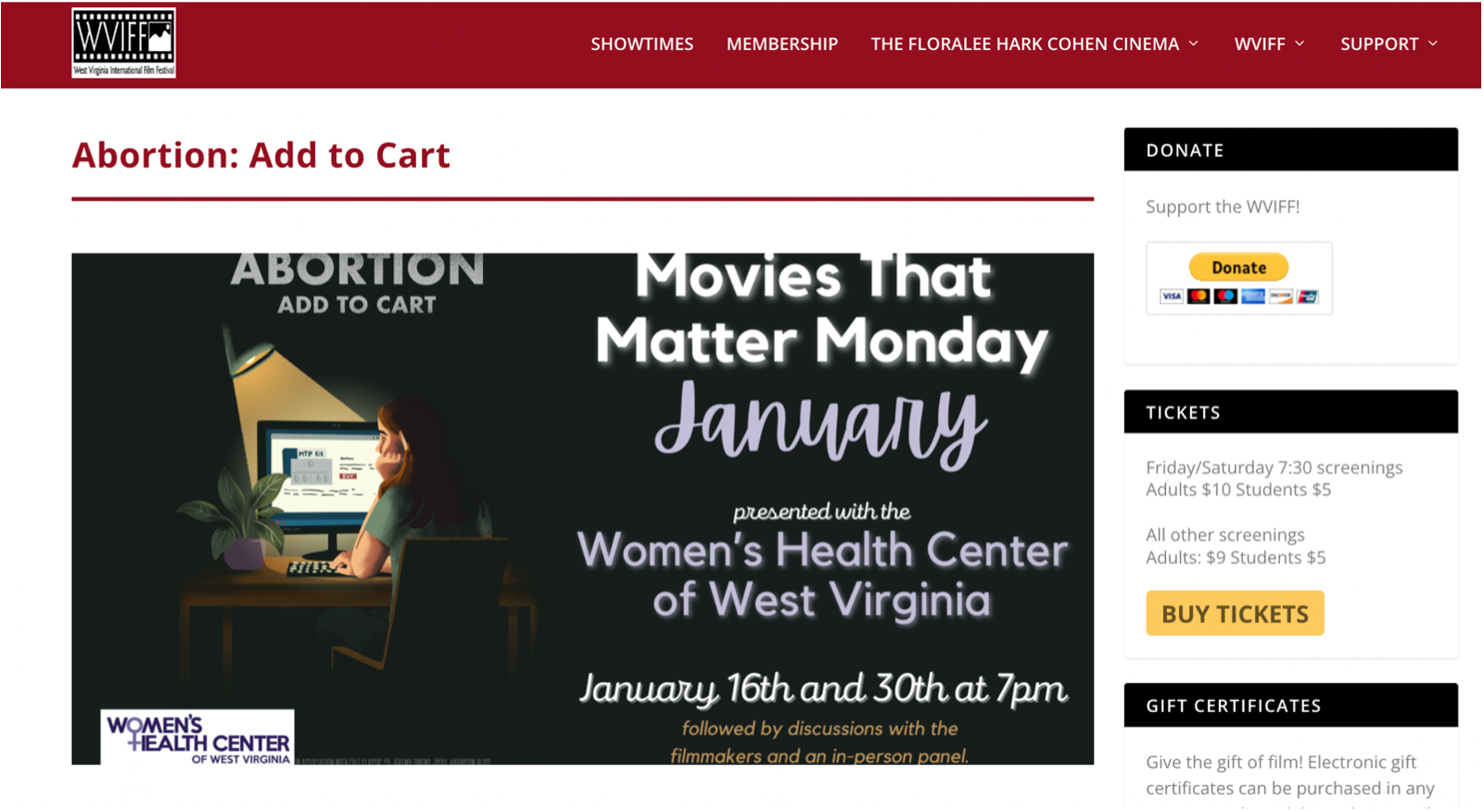

As I was feverishly writing my master’s thesis on regional American film nonprofits in January 2023, I ran across the above advertisement for a screening of Abortion: Add to Cart (Flaum, 2022), presented by the West Virginia International Film Festival in partnership with a local Women’s Health Center. The short documentary on self-managed abortion “explores the marketplace circumventing regulations to provide abortion pills over the internet” and was followed by a discussion with the filmmakers and local reproductive health experts. Tickets to the screening were “pay what you can,” a price point that is common for WVIFF’s film series “Movies that Matter Monday,” which explores issues pertinent to the lives of West Virginians.[1] Crucially, this screening took place five months after the West Virginia legislature enacted a near-total ban on abortion in the state.

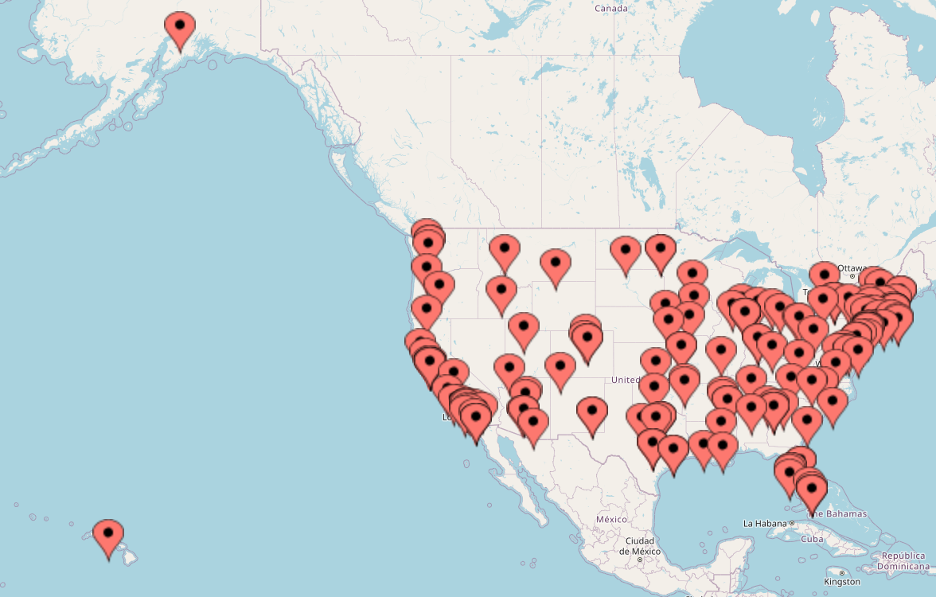

During research, I came across many programs similar to WVIFF’s “Movies that Matter Monday,” neatly packaged and steadfastly defiant. Though these programs range widely in scope and size, they share a common focus on explicitly engaging issues of resourcing, access, and equity specifically as they relate to their immediate locales. These programs sometimes take place in one of America’s media capitals, but just as frequently they lay entirely outside the network of the American film industry as it is both popularly and academically conceived. During thesis research, I created this partial map of American film nonprofits to illustrate the wide diversity of geographies and contexts in which they operate. “Movies that Matter Monday” illustrates why I think the rich, weird world of regional American film nonprofits has a lot to tell us about how film reflects, shapes, and moves through the world.

At the center of this analysis are independent film exhibitors, which I am referring to as regional American film nonprofits, that operate throughout the U.S. at a community level rather than as industry marketplaces. These nonprofits frequently act as both a film festival and arthouse, presenting one or more film festivals annually while also running year-round as independent exhibitors. The programming at regional American film nonprofits is primarily attended by local audiences rather than by the roster of filmmakers, journalists, distributors, and agents that attend industry film festivals, such as Cannes or Sundance. The West Virginia International Film Festival, for example, presents two annual festivals as well as year-round screenings and series (including Movies that Matter Monday). Rather than operating in the traditional model of a film festival as a key industry node that burns bright and fast by drawing key international players, WVIFF is instead leaning into the highly local ecosystem of audiences, programmatic partners, and volunteers to respond to concerns specific to Charleston, West Virginia.

The scope of these organizations varies greatly; Seattle International Film Festival presents year-round programming supported by 28 year-round staff members, and their marquee annual film festival clocks in at 18 days.[2] The Rehoboth Beach Film Society, by contrast, is run by two staff members and the presents several four-day film festivals.[3] An argument could certainly be made that categorizing so many diverse organizations under one term is generalizing, but for now I’m basing this approach on their shared financial and stakeholder structures, a common distribution flow, and their membership in the same professional networks. Regional American film nonprofits have received limited scholarly attention, which is why I look now to some of their unique programs to demonstrate their potential as sites of analysis for media industries studies.

For example, much like WVIFF, the St. Louis International Film Festival in Missouri is building programming out of diverse distribution flows to engage with municipal politics; 2022’s festival included a section titled “Divided City,” which focused “on the racial divide in St. Louis and other US cities.”[4] The program featured seven documentaries about racial segregation, centering St. Louis as well as towns in Colorado, Alabama, South Carolina, and Illinois. This program, predicated on a partnership between the University of Washington and the St. Louis International Film Festival, underscores the local alliances on which these small and cash-strapped film nonprofits must rely. Another program engaging with local histories of racialized resourcing can be found in Hawai’i International Film Festival’s Makawalu program, a native Hawaiian filmmaker development initiative.[5] It is also worth noting, as I explore further in my thesis, that the progressive potentials of programming that interrogates racialized resource distribution must be taken in context with the historical foundations of American independent film culture as an exclusionary space that sought to cultivate a brand predicated on a white American leisure class.

In these and other examples, the programming of regional American film nonprofits is coalescing at the intersection of independent distribution flows, complex nonprofit funding directives, and community partnership to directly engage with state and municipal political projects. Although my research has centered organizations that can feel insular to America, I also want to emphasize that I am not advocating for a step away from the rich global lens that thrives in Film Festival Studies through the work of scholars like Marijke de Valck, Skadi Loist, and Eren Odabasi. Rather, I want to illustrate how these organizations rest at the nexus of the global and the hyperlocal. By understanding how they recontextualize vast transnational film flows into programs embedded in highly local social and political contexts, we can more fully appreciate the nuanced impacts of these films and the international markets that propel them. For example, the Seattle International Film Festival’s cINeDIGENOUS program includes films from India, Canada, Taiwan, Norway, South Africa, Mexico, and Australia, engaging both global perspectives on indigeneity and the transnational film flows supporting their distribution as the organization grapples with its own relationship to settler colonialism.[6] Much like Hawai’i International Film Festival, SIFF also advertises its 4th World Media Lab under this program, a partnership between several local festivals that supports emerging Indigenous filmmakers.

As I conclude this article advocating for regional American film nonprofits, I also don’t want to overstate their importance; these organizations are small, itinerant, and financially precarious. Certainly, it is nothing new for film festivals to engage with politics, as they have always been inherently political events as outlined by Dorota Ostrowska and others.[7] Nevertheless, I am excited by what these organizations can tell us about the role that film plays in daily life, community organizing, and spacemaking and in whose lives and communities it is operating. Organizations from Birmingham, Alabama to Bend, Oregon to Portland, Maine are all forging new connections between film, local stakeholders, and their increasingly varied political contexts. Centering these organizations opens a new horizon to understanding how independent film flows are taken up by organizations in small rural communities, Midwest working-class cities, and remote mountain towns, as well as the teeming metropolises that are more frequently associated with global independent film culture. The regional American film nonprofits embedded within these communities are deliberately engaging international film flows to navigate the uniquely local circumstances of funding, politics, and environment that they are benefitted and beset by during a period of significant uncertainty and contention.

Image Credits:

- Screenshot of West Virginia International Film Festival’s programming page for Abortion: Add to Cart. (Author’s Screen Grab.)

- A preliminary map of regional American film nonprofits, with each marker representing one organization. Please note that I’m certain that this map isn’t comprehensive, as there is no formal network of these organizations and therefore creating a complete list of regional American film nonprofits poses a methodological challenge. (Author’s Screen Grab.)

- Promotional Poster for the St. Louis International Film Festival program “The Divided City.”

- “Abortion: Add to Cart,” West Virginia International Film Festival, 2023, https://www.wviff.org/abortion-add-to-cart/. [↩]

- “Programs and Competitions,” Seattle International Film Festival, 2023, https://www.siff.net/festival/programs-2023. [↩]

- “Home,” Rehoboth Beach Film Society, 2023, https://www.rehobothfilm.com/. [↩]

- “31st Annual Whitaker St. Louis International Film Festival,” St. Louis International Film Festival, 2022, https://www.cinemastlouis.org/sites/default/files/2022-11/2022_SLIFF_Digital_Program.pdf. [↩]

- “Makawalu,” Hawai’i International Film Festival, 2023, https://hiff.org/hiff-makawalu-project/. [↩]

- “cINeDIGENOUS,” Seattle International Film Festival, 2023, https://www.siff.net/festival/programs-2023/cinedigenous.. [↩]

- Dorota Ostrowska, “Making Film History at the Cannes Film Festival” in Film Festivals: History, Theory, Method, Practice, eds. Brendan Kredell, Skadi Loist, and Marijke de Valck (London: Routledge, 2016), 18. [↩]