Gazing Upwards: Spectacle, Surveillance, and Resistance in Nope

Sophia Abbey/ UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN

Nope, Jordan Peele’s recent science fiction horror film engages with themes of surveillance and spectacle, anxieties of seeing and being seen. Many readings of this film in the context of Peele’s oeuvre emphasize a turn from blackness (Get Out) and class (Us) to surveillance and spectacle in Nope. I modify and extend this reading using Simone Browne’s (2015) approach to surveillance studies—when blackness enters the frame. This reading attends to the surveillance of blackness specifically to understand the impacts of surveillance more generally through an ideological examination of genre filmmaking, themes of visibility and oppositional gaze, and a reading of dialogic elements of the movie as moments typifying Browne’s theory of “dark sousveillance,” which she describes as “an analytical frame that takes disruptive staring and talking back as a form of argumentation and reading praxis when it comes to reading surveillance and the study of it…fugitive acts of escape, resistance, and the productive disruptions that happen when blackness enters the frame” (p. 164).

Frontier narratives and the myth of the cowboy

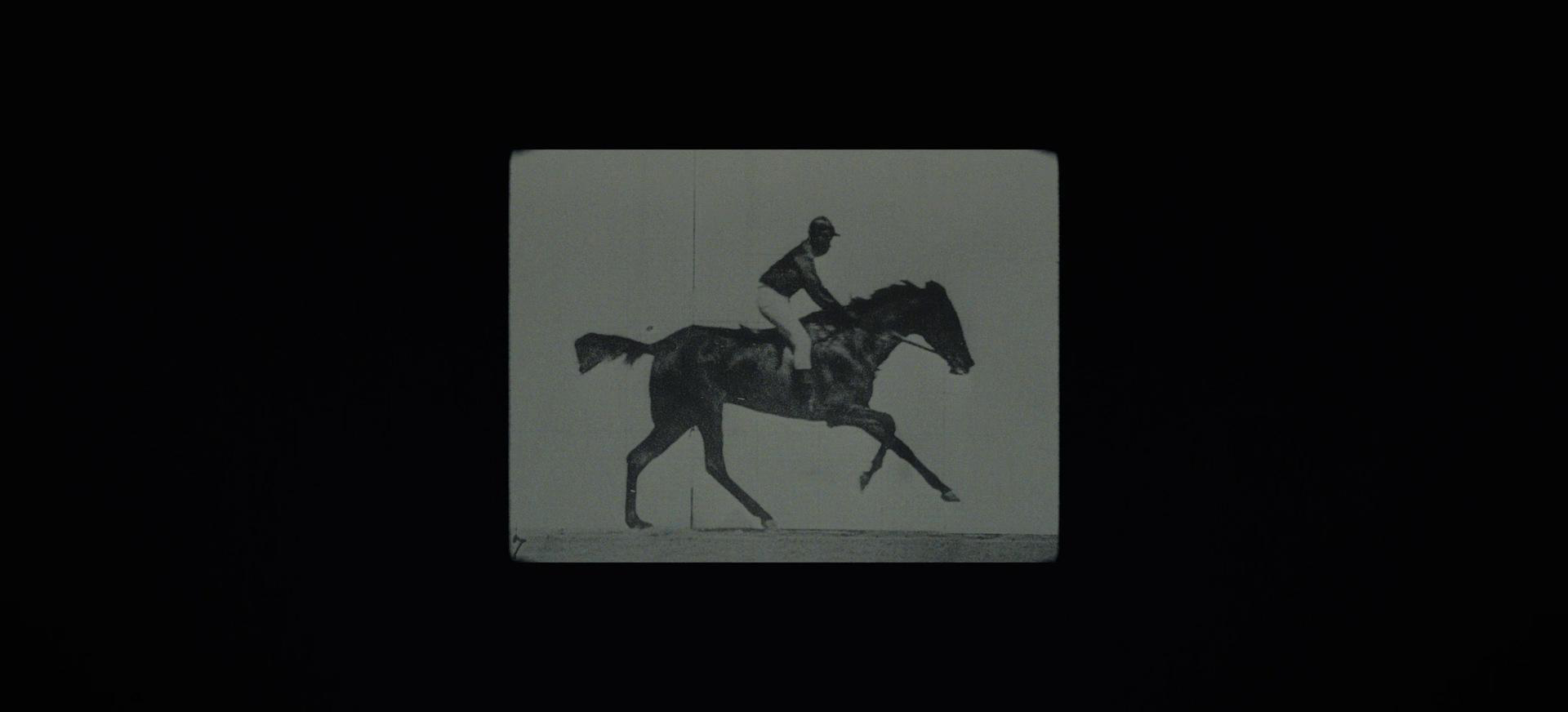

During her first scene, Keke Palmer’s character, Emerald, asks a film crew, “Did you know that the very first assembly of photographs to create a motion picture was a two-second clip of a Black man on a horse?” The crew recognizes photographer Eadweard Muybridge’s images, but nobody knows the man in the photo. Browne, too, begins her work with a recognition of what Hier and Greenberg term absented presence, or the absence of blackness in theorizations and citations, the absence of blackness from view (2015, p. 13). Peele applies critical fabulation to right this absence in Nope—recentering blackness in the history of filmmaking and, more broadly, in mythologies of the West and cowboy culture.

Both science fiction and westerns rely on American imaginations of frontiers and conquest. Charles Ramírez-Berg (2007) writes that westerns were emblematic of the Hollywood directive for “Manifest myth-making,” the purpose of which “was to rationalize – and sanitize – the history of the USA’s North American imperialism and transform it into entertaining, guilt-free narratives that conformed to core American beliefs (liberty, democracy, freedom, equality) and values (truth, honesty, fair play)” (p. 3). Peele casts Daniel Kaluuya as Otis Hawyood Jr.—a Black cowboy and Hollywood horse wrangler, subverting this myth. The film is critical of cinema’s absented presence of blackness, centering moments that challenge the hegemonic narrative. As Peele notes: “It’s about taking up that space. It’s about existing. It’s about acknowledging the people who were erased in the journey to get here” (Kennedy, 2022).

Bodies on Film: Technologies of being seen and gazing back

Nope deals with the tension between spectacle and surveillance, “spectacle” being a site of exploitation and commodification of difference and “surveillance” being the means to discipline and control that same difference. Both use tools of seeing and recording—through illumination (cinema lighting that exposes a subject on film or the use of light to make a figure legible and traceable) and capture (on cinema cameras, CCTV, or the human eye.) Illumination renders a subject legible for capture on film, and historically, camera technologies privilege light on white bodies and faces. However, light has a symbolic effect as well. Richard Dyer theorizes that there is a “general culture of light” in art and film, where light connotes purity or holiness. “This is a culture in which, as Dyer asserts, ‘white people are central to it to the extent that they come to seem to have a special relationship to light’” (Browne, 2015, p. 113). Peele uses illumination to his advantage in Nope through filmmaking techniques that amplify themes of surveillance and spectacle.

The film’s action occurs mainly at night, so to capture the detail of the landscape and actors’ faces, the filmmakers employed a classic shooting technique, day-for-night, where scenes are shot during the day and then manipulated to appear as though it were nighttime. Additionally, Peele and his cinematographer designed a camera rig specifically for the film, which held a 65mm IMAX camera and a 65mm infrared camera (Desowitz, 2022). These large format cameras offer a wider cinematic perspective than a traditional 35mm camera. Combined, these filmmaking techniques give the audience a panoptic perspective of the scene, all-seeing and all-illuminating—total visibility. At the same time, these practices resist the racist technologies of the camera that privilege light on white bodies and faces.

Illumination is also historically significant in early surveillance practices. Browne’s treatise on surveillance traces illumination as a means of control back to slavery, citing 18th-century lantern laws, which “mandated enslaved people carry lit candles as they moved about the city after dark” (p. 11). Lantern laws were a surveillance technology that made the body luminous at night while restricting sight outside the radius of the light’s spill, limiting one’s ability to see while making them more visible. Browne notes that illumination was also critical in panoptic design, which controls and contains its subjects by making the body hypervisible.

Illumination and hypervisibility may seem at odds with cinema’s absented presence of blackness. To connect these seemingly disparate themes, we can look to bell hooks’ discussion of Black domestic workers, rendered hypervisible while being expected to perform invisibility (by casting down their eyes), making sight and looking an exercise of autonomy and power. Looking is also perilous in Nope, whose antagonist, Jean Jacket, is drawn to the direct gaze of others. Nope emphasizes the eye as vulnerable—Otis Senior dies when a coin pierces his skull through his right eye, and one of the Haywoods’ horses is startled by the reflection of his eye in a visual effects mirror ball. Nevertheless, Otis Jr. and Emerald tempt fate in their efforts to capture a sellable image of Jean Jacket—installing security cameras around their property and hiring Antlers Holst, a cinematographer, to get “the impossible shot” on film. Cameras repeatedly appear in the text as tools of art and surveillance but also become means of resistance in the hands of the Haywoods, in defiance of Jean Jacket’s control over what they can see. The eye, the camera, and the act of looking are not only dangerous but an exercise of power.

Hell no and other moments of dark sousveillance

Surveillance culture imbues seeing with knowledge and control, while being seen is vulnerable and restrictive. However, Nope bestows power in looking back in order to both see and evade capture by the alien predator. Here, I imagine Browne’s theory of dark sousveillance at play within the film as both a dialogic element and a resistive practice of blackness. Dark sousveillance is a resistance to anti-Black surveillance rooted in Black epistemologies, “where the tools of social control…were appropriated, co-opted, repurposed, and challenged in order to facilitate survival and escape” (Browne, 2015, p. 21).

First, we must understand Nope as a Black horror film, one that positions itself within the context of Black life and considers the Black audience (McEntee, 2022). Black horror differs from typical horror, in which the Black body is dispensable and killed first—a trope so recognizable that it warrants a feature-length satirization. In Nope, the characters evade this fate in part through dialogic resistance—when Otis Jr. and Emerald say “no.” In one of the film’s first tense and suspenseful moments, Otis Jr. investigates a sound coming from the stables (investigating strange noises is the death knell in horror.) As he approaches, two figures appear, and he backs away quickly, saying, “Nope. Mm-mm. Nope, I’m out, I’m going. Fuck this shit.” He refuses to explore further, rejecting the familiar fate of other characters in horror. These moments of resistance and refusal disrupt these tropes of danger and precarity for Black characters; the definitive “Nope” is a declaration of resistance and an intent to survive.

Peele’s Nope captures anxieties of surveillance culture and power in spectatorship, collapsing the two to explore what is seen, what is unseen, what is watched, and what gazes back. The film recenters race in the narrative, contextualizing blackness within power, control, resistance, and exploitation. Nope is at once a love letter to filmmaking, a memorial to the spectacle of cinema that Peele is anxious about losing, and an account of anxieties regarding technologies of surveillance and control. He explores these possibilities narratively, thematically, and para-diegetically, using technical practices to immerse the audience and make them witnesses.

Image Credits:

- Still from Nope, dir. Jordan Peele (2022)

- One of Muybridge’s studies of motion, as seen in Nope

- Otis Jr. and Ghost gaze at the sky

- Jean Jacket hovering above Otis Jr.’s truck (author’s screen grab)

- Otis Jr., in silent communication with his sister (author’s screen grab)

Browne, S. (2015). Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. Duke University Press.

Desowitz, B. (2022, July 24). ‘Nope’: How they shot those spectacular night scenes. Indiewire. https://www.indiewire.com/2022/07/nope-jordan-peele-night-scenes-1234743477/

Kennedy, G. D. (2022, July 20). Jordan Peele and Keke Palmer look to the sky. GQ. https://www.gq.com/story/gq-hype-jordan-peele-and-keke-palmer

McEntee, J. (2022). The Tethered Shadow: Jordan Peele and Stanley Kubrick, Film Criticism 46(1). https://doi.org/10.3998/fc.2715

Peele, J. (2022). Nope [Film]. Universal Pictures.

Ramírez Berg, C. (2007). Manifest myth-making: Texas history in the movies. In D. Bernardi (Ed.), The Persistence of Whiteness: Race and Contemporary Hollywood Cinema (pp. 3-27). Routledge.