Our Future is Garbage: Rejecting Climate Despair in Speculative Science Fiction

R Baker / University of California, Santa Barbara

“With Earth no longer habitable, the only place left to go was up”

—Space Sweepers (승리호), dir. Jo Sung-hee (조성희), 2021

To engage in a serious, sustained contemplation of climate change often feels akin to staring, wide-eyed and frozen in terror, into the headlight of an oncoming freight train. Our newsfeeds bombard us with videos of dying polar bears and vanished habitats, mountains of grim data on extreme weather events, and multicolored charts confidently predicting devastation within decades. Images of melting ice caps, trash islands, and hordes of climate refugees form a strange bricolage overlay to greenwashing campaigns funded by big oil, politicians who confidently promise change before signing the next big pipeline into existence, and climate protests violently broken up by militarized riot police, who shamelessly protect corporate interests over human lives. The sheer dissonance between this rising tide of information[1] and political inertia on policy change, the drudgery of day-to-day work emails and deadlines somehow existing side-by-side with reports of imminent global cataclysm feels—to put it bluntly—nothing short of insane. It’s no wonder that climate deniers are a vanishing breed, rapidly being replaced by “doomers”—a generation of people, many of whom are Gen Z or younger, who’ve given up hope that climate change can be stopped or mitigated in any meaningful way. Deftly throwing a wrench into the classic liberal idea that more information is always better, the onslaught of facts surrounding climate change feels the opposite of empowering. Instead, it engenders a kind of doomscrolling despair, what environmental scholar Heather Houser has dubbed “infowhelm“[2]: the feeling of being entangled and incapacitated by a web of information with no hope of rescue—and, even more dangerously, with the inability to imagine any kind of alternative future[3]. Cynicism reigns supreme; helplessness, grief, and rage braid together and form a noose, specially fitted for gallows humor at the end of the world.

Needless to say, despair is a dangerous thing—even more so, perhaps, than denial. Climate despair not only robs us of individual hope but also, by proxy, of the idea that meaningful, collective action surrounding climate futures is even possible. It engenders fatalism, alongside an understandable (but misplaced) anger toward older generations. At its worst, it breeds the kind of monstrous, zero-sum thinking that leads the wealthy to invest staggering amounts of cash on doomsday bunkers, or to self-styled maverick scholars suggesting the large-scale culling of elderly citizens in the name of economic progress. Like its autocratic cousins, ecofascism comes in many guises, often dressing itself in the apparently innocent trappings of logic and free discourse that’s “just asking questions”.

As a scholar of science fiction and the environmental humanities, people often ask me how I can possibly conceive of my work as hopeful. Laying aside the much larger question of what science fiction can “do” in the service of social and climate justice, this is a fair question.[4] Disaster sells, as does escapism. Hollywood and major publishing firms aren’t usually interested in paradigmatic disruptions of the status quo. As a result, dystopian climate fictions all-too-often concern themselves with the affect of apocalyptic devastation ,at the expense of environmental critique: the junked cars and wasted shells of nuclear reactors piled on the roadside in popular films like the Mad Max franchise, or the vertical stacks of dilapidated coffin hotels and cyberpunk back-alley shops glinting with broken motherboards that grace the pages of Neuromancer, generally boil down to mere aesthetic flourishes. In these texts, a climate-devastated Earth littered with trash is just the hellish, visual reminder of great wars, nuclear winters, and corporate fascism—a hollow remnant of a bygone world, acting as a backdrop to the hero’s journey toward vengeance or redemption. While there may occasionally be a happy ending for a scrappy survivor or two, the world itself remains broken beyond ecological or cultural repair.

Climate change has been accurately described as “the problem from hell:” massive, multifaceted, and mind-bogglingly complex, diffused over more-than-human timescales, and metastasizing along myriad political, cultural, and economic axes that extend far beyond the range of individual comprehension. It’s no wonder climate change doesn’t lend itself easily to self-contained, often-anthropocentric narrative media forms.[5] Even when narrowing our focus considerably, from “climate change” writ large to narratives that deal explicitly with garbage and junk as major, worldbuilding plot devices (a stand-in for ecological devastation on larger scales),[6] stories that successfully reject climate despair seem few and far between.

But perhaps we’re asking the wrong questions. If the problem of climate despair in popular culture seems insurmountable (and thus inexpressible) from an individual human’s perspective, then what happens when the protagonist is not human—or is not an individual? What happens when the characters in question aren’t in combat against the apocalypse itself, but rather against the normative, dominant systems which brought it about? What if the age-old narrative formula of an indefatigable hero, fighting alone to save the world, is not the solution but rather the problem?

What if the ongoing literary project of curtailing climate despair, of utilizing speculative fiction as a means to envision climate futures and hope in the midst of the Anthropocene, hinges not on the speculative restoration to “normal”, but rather upon its outright rejection?

Many sci-fi narratives dealing with trash-filled dystopias appear, at first, to be little more than a retelling of the same old apocalypse. But on closer inspection, a handful of these narratives reveal themselves to be an intriguing re-speculation—a salvaging, if you will—of non-anthropocentric, even revolutionary climate futures built from the ashes of the past. Pixar’s animated film WALL-E (2008) is perhaps the best-known example of such a tale. It pictures a future in which unchecked consumption and human greed—synecdochally represented by the corporate superpower Buy & Large—has turned the Earth into an uninhabitable landfill. The eponymous WALL-E (“Waste Allocation Load-Lifter: Earth-class) is a sentient robot worker who is to clean up literal mountains of trash after humans flee the now-toxic planet. The plot eventually involves WALL-E undertaking a hero’s journey to lead the remaining humans back to Earth, centuries after their flight. Nevertheless, it’s clear that this is not an anthropocentric, victorious homecoming. The robot does not (and cannot) lead the frightened descendants of its creators “home”; its world is one we forfeited long ago, and is no longer ours. The closing credits of the film hint at the slow restoration of the planet alongside a collective cyborg social order, where humans are learning from and laboring alongside the very machine life their long-dead ancestors callously abandoned.

Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (1968) is another example of a depopulated, largely junked wasteland, overflowing with obsolete equipment, trash, forgotten tchotchke, food wrappers, old newspapers, etc, collectively known as “kipple.”[7] Although it may seem strange to characterize Dick’s hardboiled cyberpunk dystopia as hopeful, the novel nevertheless offers tantalizing glimpses of a radically recombinant, non-anthropocentric climate futures in the wake of a consumer-centric, dying human world. Even as the plot centers on human bounty hunter Richard Deckard, tasked with discovering (and murdering) escaped androids trying to pass as human, the creeping, ubiquitous mass of kipple is almost a character in its own right. While pet ownership has been elevated to the level of religious devotion, the mass influx of “electric” animals in the story represents an economically feasible but socially embarrassing substitute for the genuine article. Similarly, “ersatz” human androids are employed as essential workers in dangerous, toxin-filled environments, but face vitriolic hatred from Deckard and other organics, who obsessively gatekeep the boundaries of their species. But as humans become sterile and the number of surviving organic animals dwindles to near-extinction, electric life flourishes. Kipple multiplies like a fungus underfoot, filling abandoned apartment buildings, rising slowly like a tidal wave; it quivers across and through every landscape and plot point, slowly overtaking the novel and melding all life—organic and electric alike—within itself. The psychedelic closing scenes of the novel depict a guilt-ridden Deckard experiencing forgiveness and redemption in this wash of trash, a religious epiphany of absolute entropy in which reality and VR, life and death, machine and organic become fused into a singularly ambivalent, yet radically inclusive posthuman milieu.

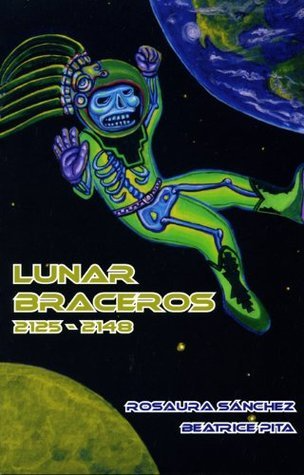

Finally, Rosaura Sanchez and Beatrice Pita’s novel Lunar Braceros: 2125-2148 (2019) depicts a neoliberal-dystopian future where political prisoners and the debt-bound poor serve as slave labor, sent to the Moon to handle the masses of radioactive waste that have overflowed the storage facilities on Earth. But one day, on a routine inspection, the wasteworkers open an improperly sealed container to find the bodies of the previous crew. Further investigation reveals that, according to the corporate bottom line, transporting imprisoned workers off the Moon is simply not worth the expenditure. Like the trash they handle, their labor has reached the end of its extractable value. With nothing but their lives left to lose, the braceros team up to orchestrate a daring escape from their moon-based prison. They successfully hijack a shuttle at gunpoint and escape deep into the Amazon, finding sanctuary with political allies in an Indigenous-led collective operating outside the control of corporate fascism. The novel itself is written in a non-linear form that echoes its commitment to collective futures, featuring the myriad narrative voices of the wasteworker crew: it bounces between recollected vignettes, history and science lessons, commentary from multiple interlocutors, incisive political analyses, and a fugitive mother’s fervent hope for her child, who against all odds was born free outside the system that nearly killed her. Present, past, and future shuffle and overlay one another, shifting their meaning and import in relation to each other, as the novel theorizes climate futures in terms of alternative kinship networks and redistributive justice. While Lunar Braceros—unlike the other two “trash” science fictions I discuss here—features exclusively human protagonists, its commitment to shifting notions of value away from a monotropic focus on individual success or survival, and towards a politics of collective care, place it firmly in the realm of speculative fictions that combat climate despair.

Tellingly, the garbage-infested infrastructure of these storyworlds are invariably populated by a working underclass—human or otherwise—which itself is considered expendable, simultaneously forgotten and reviled—who for that very reason play a crucial role in jarring a stagnant society into a radically different worldview. These climate fictions are thus inseparable from the social critique they engender, linking climate and class justice as two sides of the same coin. They reject both doomsday despair and the escapist fantasy of returning to a pre-crisis world. Instead, these narratives navigate crisis itself as the fraught ground from which the possibility of both climate hope and revolutionary social change may arise.

Image Credits:

- Concept art for Pixar’s WALL-E, dir. Andrew Stanton (2008)

- “Cap Plan,” original art by Dug McFarlane

- Cartoon from The New Yorker, Nov 25, 2012, by artist Tom Toro

- Screenshot from Mad Max: Road Warrior, dir. George Miller (1981)

- Screenshot from Automata, dir. Gabe Ibáñez (2014)

- AI-generated conceptual artwork for Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep posted by starryai, June 25, 2022, r/aiArt

- Cover art by Mario Chacon for Lunar Braceros

- This includes the 2018 United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) special report, detailing the global effects of a 1.5 Celsius rise in temperature above pre-industrial levels—the major takeaway being that Earth has until 2030 to cut carbon emissions by 40-60% in order to avoid the worst of climate disaster. You can imagine how that’s going so far. [↩]

- Houser, Heather. Infowhelm: Environmental Art and Literature in an Age of Data. Columbia University Press, 2020. [↩]

- Ray, Sarah Jaquette. “Introduction.” A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety: How to Keep Your Cool on a Warming Planet. University of California Press, 2020 (pp 11-14). [↩]

- For an excellent, beginner-friendly resource on how science fiction can function as an activist lens that grapples with the myriad social challenges of the 21st century, see Sherryl Vint’s Science Fiction (MIT Press, 2021). [↩]

- See also: Ghosh, Amitav. The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable. The University of Chicago Press, 2017. [↩]

- It goes without saying that garbage and pollution/waste are not synonymous with the climate crisis, which is largely driven by unchecked carbon emissions and rising global temperatures. However, it would be difficult to overestimate the ways in which doomsday visions of a trashed, pollution-ridden Earth drive much of the contemporary conversation (and rhetorical urgency) surrounding human climate futures, as well as the extent to which much environmental justice discourse begins—though doesn’t necessarily end—with a critical examination of garbage dumps and toxic pollutants. See, for example, Robert Bullard’s Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality (1990), and Max Liboiron’s Pollution is Colonialism (2021). [↩]

- Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), though a masterpiece in its own right, unfortunately elides the omnipresent question of “kipple” altogether—rather than portraying dystopia as a creeping despair in which all beings are slowly being drowned in a relentless ocean of meaningless junk, the film opts for a more exciting, inner-city cyberpunk aesthetic, in which Deckard’s questioning of his own humanity—rather than his eventual, exhausted submergence into all which is nonhuman—serves to drive the narrative conclusion. [↩]

What a thought-provoking and well-reasoned article. I like how you ended the article by highlighting the intersectional relations between the climate crisis and class struggle. And I think it’s not just the “working underclass” that makes this analysis poignant, but the techno-capitalist/accelerationist megastructure (which generated that underclass) that crops up in all three novels you cited––systems that spawned both the crisis and its posthuman “solution” (as in WALL-E and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep). But it does make me wonder if that puts these texts in tension with the distinctly neo-Luddite conclusion of Lunar Braceros. In other words, how compatible are techno-posthumanism and anti-colonial deep ecology? While they agree in their critique of anthropocentrism, synthesizing them seems to challenge one to re-conceptualize the natural-artificial antagonism. Anyway, exciting stuff!