Viewing Women Readers: Digital Culture and Feminist Close Reading

Michele White / Tulane University

On Twitter, and among my Facebook friends, comments about (close) reading are often accompanied by photographs of piles of books that have been or may be read. These representations are designed to be read and to craft an image and conception of the reader and poster. When first doing an image search for close reading memes, I immediately noticed that most of the initial representations were of men. For instance, there were only two women and two animals (an armadillo and a dog) on the first screen of Google Images results.[1] As I suggest later in this article, reading was and is culturally informed by a series of gender norms and stereotypes. I argue that feminist forms of close reading offer additional means of engaging with texts and methods of considering the ways normative notions of bodies and hierarchies are reproduced through representations of readers.

Memes suggest that the people who are engaged in close reading practices tend to focus on the specificities of texts and that these practices are time intensive, which is also emphasized in the academic literature.[2] For instance, an image of a white male “English Major” with his teeth clenched and eyes slightly widened is accompanied by the indication that “one paragraph of text” results in “eight pages of close reading.”[3] Close reading is thereby misrepresented as excessive. Memes also indicate that engaging with a text is not just a process of foregrounding a few of its facets. Thus, the knowledge and practices required to perform a close reading are evoked by a meme that argues, “one does not simply underline a passage and call it close reading.”[4] While these memes highlight the skills that enable close reading, feminist and other forms of close reading, as I indicate in this short article, are also everyday digital practices. Individuals develop, share, and claim close reading as part of their digital media competencies.

Close reading is a key research practice in humanities disciplines, including in the study of art, film, literature, and media. While close reading is often associated with a small canon of important works, feminist forms of close reading underscore the reasons to engage culture more broadly and to emphasize the political possibilities of analysis. Feminist close reading thereby pays attention to producers who have been marginalized and to the ways women and other oppressed individuals are addressed and represented.[5] These queries should be centered in digital media studies. Yet despite digital forms of everyday close reading, there has been little review of how close reading, including feminist practices, are components of digital engagements and can be employed to study digital interfaces, hardware, software, and online communication. Exceptions to this include the ways N. Katherine Hayles, Matthew Kirschenbaum, and Sarah Stang emphasize the importance of close reading to new media studies.[6] Hayles offers methods of digital close reading and defines it as the “detailed and precise attention to rhetoric, style, language choice,” and other features of texts.[7]

Digital forms of close reading should include an address to banners, logos, help and search forms (and what language is automatically suggested), “about” and FAQ pages, terms of service statements and company descriptions, options for personalization, and repeated terms and punctuation. The ways individuals and users are addressed and depicted should also be aspects of digital close reading practices that provide methods of understanding our experiences with technologies and how they produce identities and bodies. This includes an analysis of icons and logos that depict the ideal user, the colors and other design elements that welcome some people and render facets of their identities, the avatars that individuals can select (or be assigned) as part of their engagement, the compilation of behaviors that produce data images, and emoji that convey the sentiments and bodies of individuals. These areas of consideration can be elaborated upon and expanded when doing feminist close reading of digital sites, including the ways gender and power are articulated.

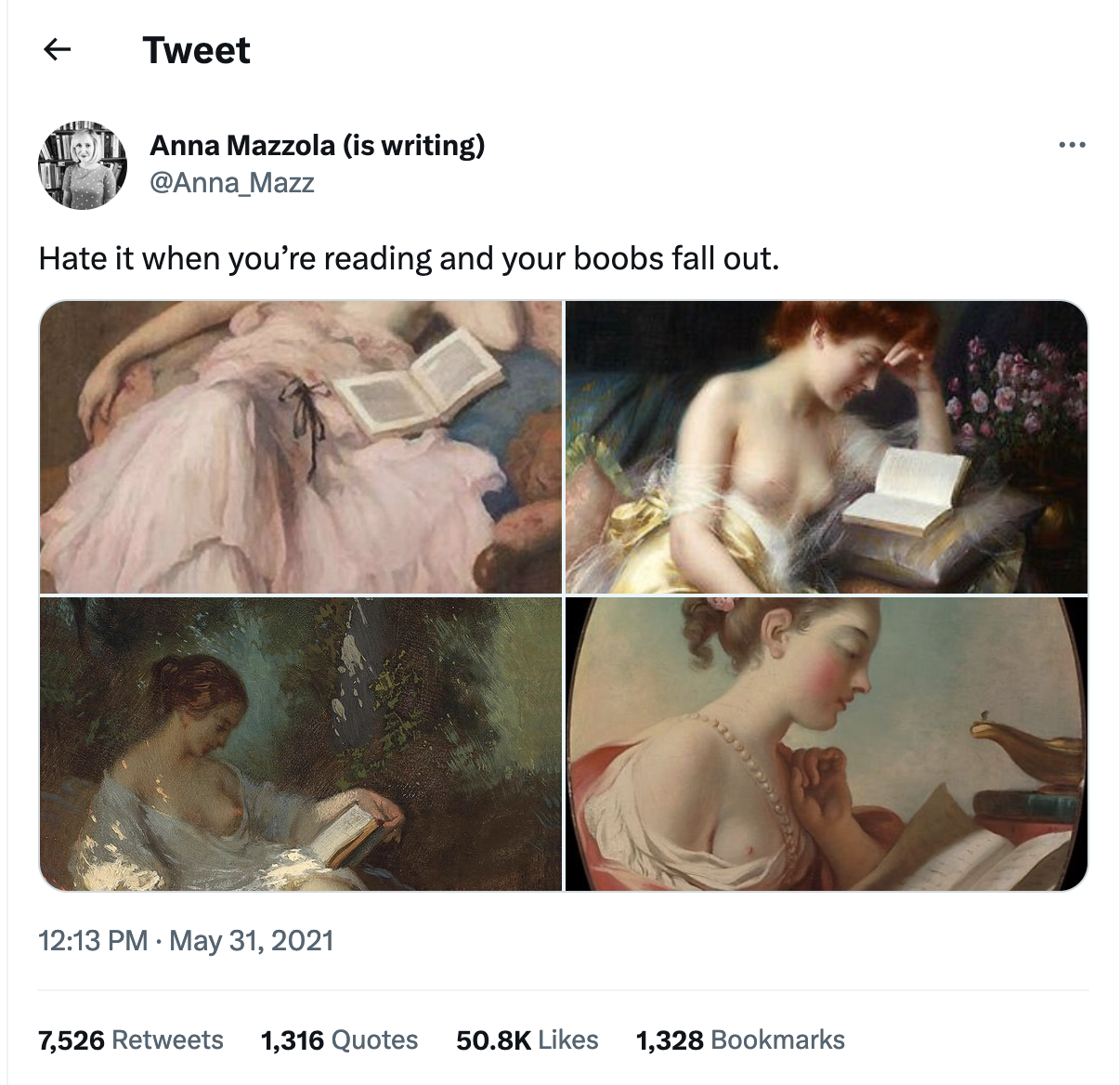

Close reading, including feminist close reading, should be identified as a productive method of digital study because it is related to everyday engagements. People analyze posts and memes, the self-representations of influencers, and the veracity of emails and URLs. Feminist forms of popular close reading include the Jezebel website’s “Photoshop of Horrors” posts where the airbrushing of women is critiqued.[8] As part of the Twitter menwritewomen account, individuals collaboratively analyze the ways women are misrepresented.[9] They foreground how women (and women readers) are misogynistically portrayed as passive and reclining in a manner that makes them available to the gaze of spectators, consumable, prudish and/or excessively erotic, more interested in their visual appearance than the text that they are reading, distracted, and lazy.

Feminist close reading practices can be attentive to the kinds of representations of gender positions that I discuss in this short article, including depictions that assert what women readers are supposed to be and how they are supposed to perform. Feminist close reading also analyzes how other subjects are depicted and the cultural implications of these representations. In digital settings and technologies, this includes studying presumptions about the individuals who employ technologies, the gender and other coding of sites and technologies, and thus the identity scripts that are produced by designers, companies, and participants. These scripts are embedded through a variety of strategies in the features of digital and other objects and sites. Given that feminist forms of close reading should be intersectional and address ways different subject positions combine in influencing conceptions of individuals and their lived experiences, these methods of analysis can also focus on class, disability, race, sexuality, and other identities that are articulated as ways of empowering and/or disenfranchising individuals and groups. This includes considering how power is rendered and displaced even when, and sometimes especially when, women and other oppressed subjects are not overtly mentioned or represented.

Feminist forms of close reading are enacted on the aforementioned platforms as well as on some other sites. For instance, Anna_Mazz uses Twitter to critique the traditional representational strategies that are employed when portraying women as close readers, including the eroticization of women’s bodies. She presents four closeups of paintings where women are depicted reading. In each of these images, women’s gowns appear to slip off their bodies so that their breasts are revealed. Anna_Mazz questions this visual device and writes, “Hate it when you’re reading and your boobs fall out.”[10] Many individuals responded to Anna_Mazz’s post with their own critical comments. They interrogated additional images of nude and partially clothed women reading. Such images suggest how artists and illustrators use the woman reader as a structuring device and figure women’s bodies as immobile, distracted, and available to the gaze.

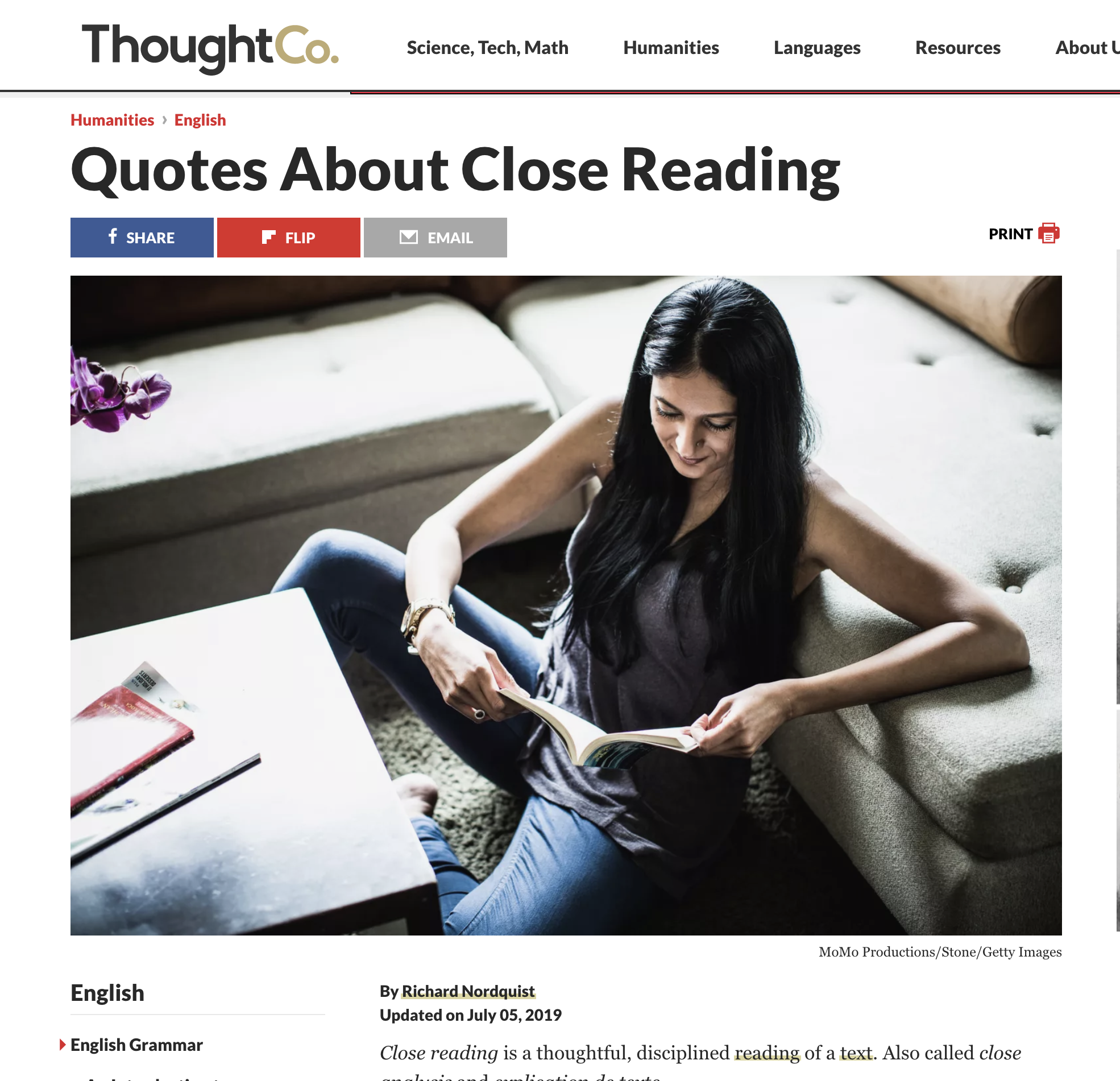

Feminists critique how women are diminished and scripted by some representations of women reading, but close reading is still too often associated with conventional ideas about gender norms and hierarchies on Internet sites. For instance, Richard Nordquist’s “Quotes About Close Reading” is accompanied by Momo Productions’ image of an all too familiar passive feminine reader. She rests on the floor with her legs spread and eyes directed downwards so that she does not disrupt the viewer’s gaze.[11] Her foot and legs are suggestively and uncomfortably positioned to further direct the view. The heel is pointing at her crotch, but it is also a kind of uninvited phallic object. The viewer’s attention is also organized by the “V” of the book spine, which emphasizes the “V” of her blouse and the upside down “V” of her spread legs. Her tentative hold on the thin book and slender body suggest that she is unserious and an unscholarly text to be read rather than an attentive close reader, and thus that she is to be looked at because her reading is light.

The image proscribes her role. She is boxed in by the furniture frame within the cropped photographic frame. Her arms and the book form another messier containment structure for her body. The book is also employed as a framing device to explain and control her downcast look. It is not even clear if her head is tilted in the necessary position for her to look at and read the book. Her position on the floor allows the photographer/camera/viewer to look down at her. The employment of the camera to position the viewer above the depicted woman reader is a common feature of these renderings and of portrayals of women more generally.

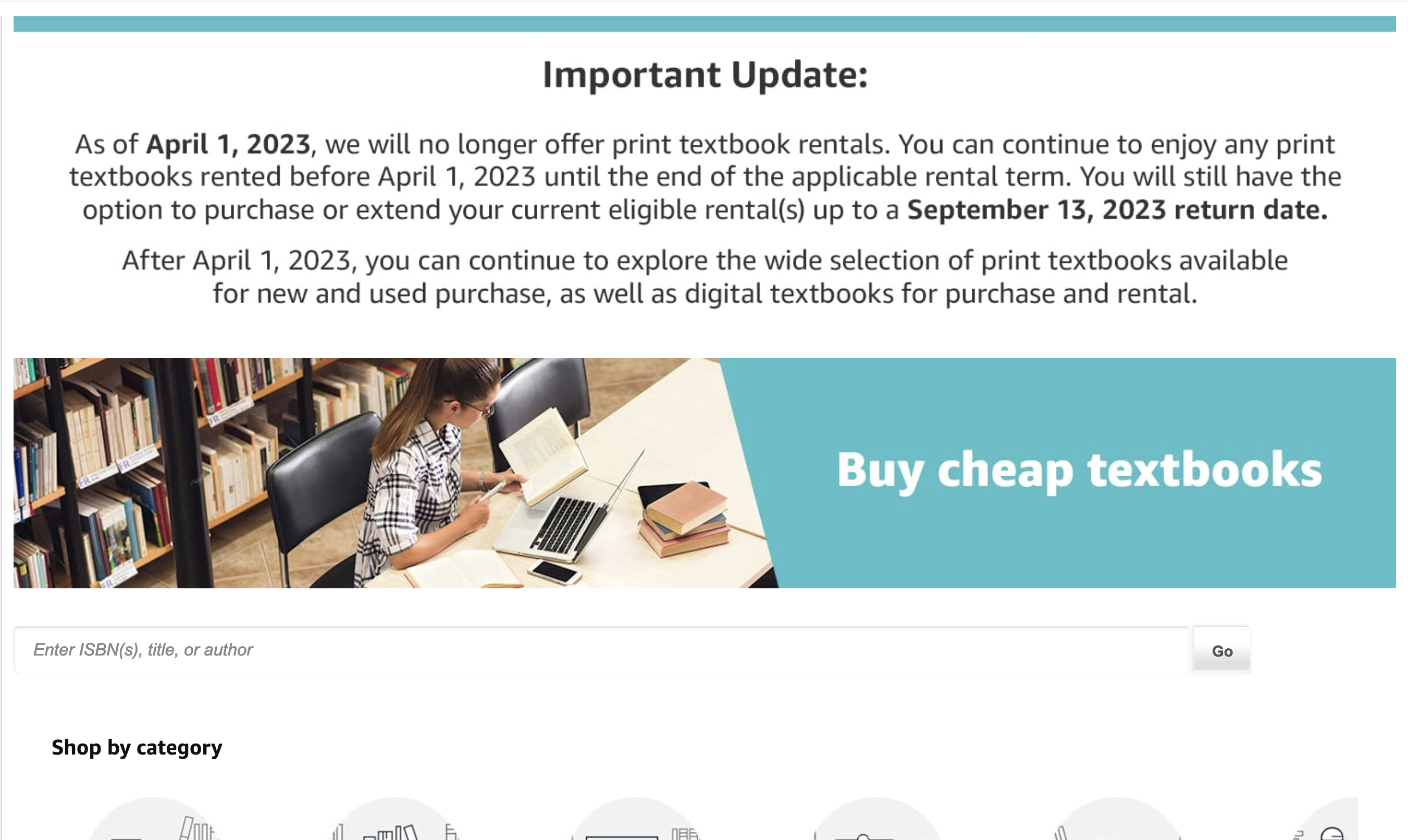

An image that accompanies the registration for a “Feminist Lens’ Book Club: Grades 8-12” establishes an even more elevated position so that the women readers’ ability to gaze is erased. So too are their bodies pushed to or beyond the edge of the frame.[12] The viewer of this advertisement is thus positioned above and as a kind of orchestrator of a series of hands that hold books in different positions. Amazon similarly positions the viewer above an image of a woman with long hair in its update, which indicates that the company is no longer providing print rentals of textbooks.[13] In Amazon’s image, the woman’s head is similarly positioned along the top edge of the frame so that part of her brain is removed. The thinness of the book that she holds is comparable to the volume in the image that accompanies Nordquist’s list of quotes. These depictions render women as objects rather than subjects. This persistent framework for figuring women readers thus provides a limiting script for how women are thought to read and how they are culturally understood. Amazon unfortunately elaborates on these stereotypes. It incorporates the woman’s image into a banner that indicates, “Buy cheap textbooks” and suggests that she may also be cheap. The concept of cheapness is especially detrimental when associated with women. It implies that they are erotically available to other people and that their sexuality is not acceptable or important.

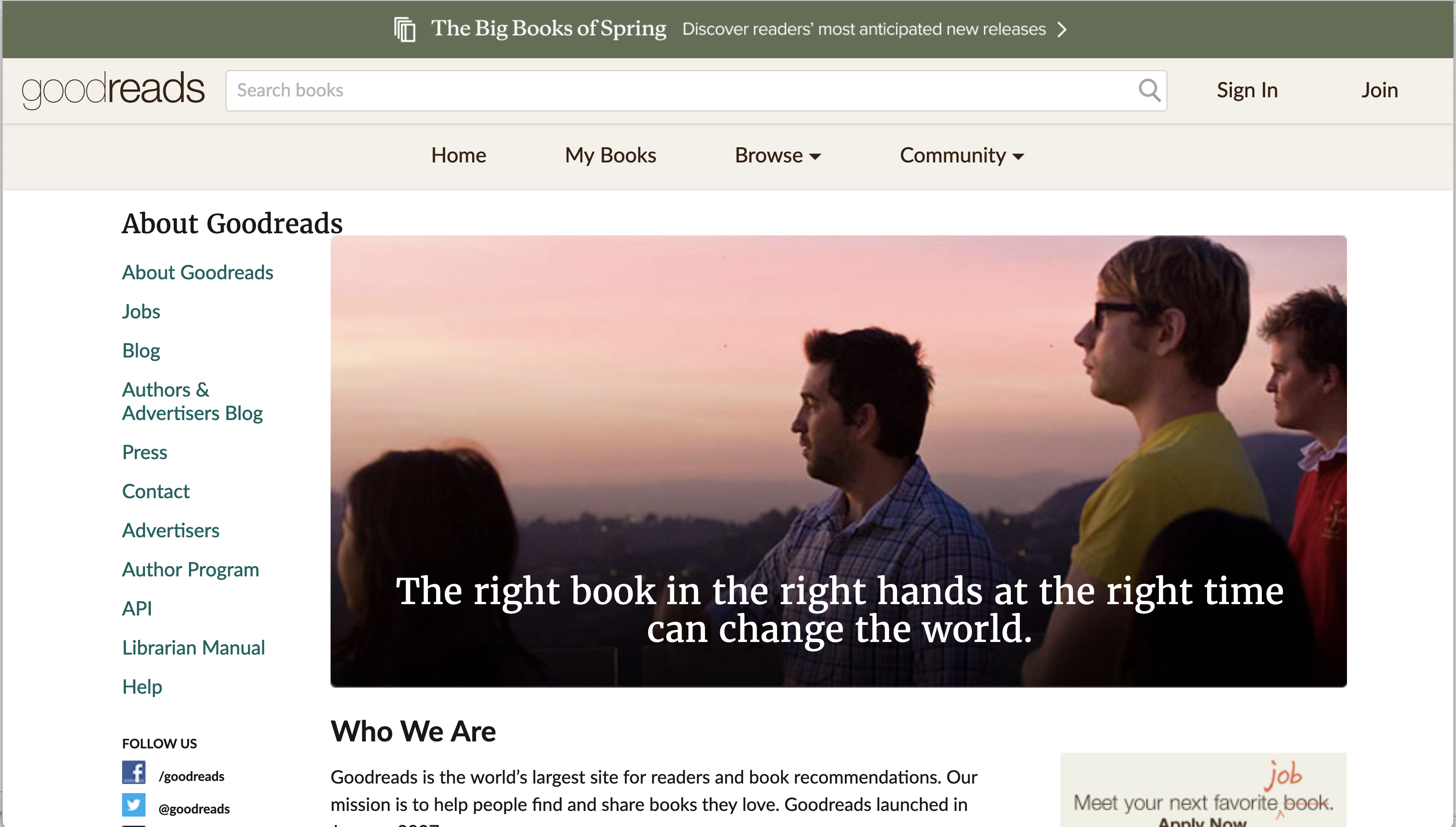

Many of the images of women readers that I discuss in this article contain them, look down at them, and position them at the edges of frames. However, Goodreads associates its site with a series of more elevated men. The “About Goodreads” page includes a carousel of images with the message that the “right book in the right hands at the right time can change the world.”[14] The associated images depict a totemic series of illuminated bookcases, a lit-up cityscape, and two standing and henge-like men (and one standing individual who is cut by the frame). While there may be other gendered readers depicted, they are difficult to identify because they are pushed to the bottom of the frame and seen from behind.

As the representations that I consider in this article suggest, the reader can be employed as a critical feminist strategy and as a means of reproducing norms. Feminist close reading might thus highlight the ways gender and other identity positions are constructed and constraining and feminist academics’ positions as active and agile readers. Feminist close readings of Goodreads and some of these other texts can also indicate how ableist visions of correct hands are rendered. The site and slogan do not address all the ways hands and bodies are positioned in relation to books and reading. Goodreads risks pulling books out of some people’s hands even as it positions the ways individuals are understood. So too do the affordances of the associated sites and the white hand-pointers through which we engage with reading and viewing constitute scripts for close reading and ways of engaging with texts and technologies. After all, one of the shifts from representing print to digital readers has been a focus on the ways hands are positioned on and near screens. Too often these hands, like many of the represented bodies of readers studied in this article, are light skinned. White pointing hands are also, as I suggest in the Flow article “Touching Feeling Hands: Gender, Race, and Digital Devices,” one of the primary representations of users and a continued aspect of reading culture.[15] Instead of adopting these positions and attaching ourselves to the empowered hands and bodies that only demarcate some people’s situations and identities, feminist close reading can offer ways of analyzing these representations and propose an array of critical and corporeal positions.

Image Credits:

- Figure 1. quickmeme, “close reading is a life strategy – English Major Armadillo.” (author’s screen grab)

- Figure 2. quickmeme, “one paragraph of text eight pages of close reading – English Major.” (author’s screen grab)

- Figure 3. Anna_Mazz, Twitter. (author’s screen grab)

- Figure 4. Momo Productions, “Quotes About Close Reading,” ThoughtCo. (author’s screen grab)

- Figure 5. Amazon, “Amazon.com: Save up to 90% on rental, new, used, and digital textbooks.” (author’s screen grab)

- Figure 6. Goodreads, “About Goodreads.” (author’s screen grab)

- Google, “‘close reading’ memes,” 3 August 2022,

https://www.google.com/search?q=%22close+reading%22+memes&tbm=isch&ved=2ahUKEwi

Eoov58Kv5AhX1oWoFHW-lCzEQ2-

cCegQIABAA&oq=%22close+reading%22+memes&gs_lcp=CgNpbWcQAzoECCMQJzoECA

AQQzoFCAAQgAQ6CAgAEIAEELEDOgcIABCxAxBDOgYIABAeEAU6BggAEB4QCDoEC

AAQGFCZDVjYMmCaNGgAcAB4AYABvwKIAfsOkgEIMTkuMi4wLjGYAQCgAQGqAQtn

d3Mtd2l6LWltZ8ABAQ&sclient=img&ei=egzrYoT9CPXDqtsP78quiAM&bih=913&biw=1701;

quickmeme, “close reading is a life strategy – English Major Armadillo,” 27 March 2023,

http://www.quickmeme.com/meme/35r3hv. [↩] - Nicole Shukin, “The Hidden Labour of Reading Pleasure,” English Studies in Canada 33, nos. 1–2 (March–June 2007): 23–27. [↩]

- quickmeme, “one paragraph of text eight pages of close reading – English Major,” 27 March 2023, http://www.quickmeme.com/meme/gl6 [↩]

- One Does Not Simply, “one does not simply underline a passage and call it close reading,” Meme Generator, 6 August 2022, https://memegenerator.net/instance/65145677/one-does-not-simply-one-does-not-simply-underline-a-passage-and-call-it-close-reading [↩]

- Franco Moretti, “Conjectures on World Literature,” New Left Review 1 (January–February 2000), 30 March 2023, https://newleftreview.org/issues/II1/articles/franco-moretti-conjectures-on-world-literature. [↩]

- Matthew Kirschenbaum, Mechanisms: New Media and the Forensic Imagination (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008); Sarah Stang, “Too Close, Too Intimate, and Too Vulnerable: Close Reading Methodology and the Future of Feminist Game Studies,” Critical Studies in Media Communication 39, no. 3 (2022): 230–38. [↩]

- N. Katherine Hayles, How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 58. [↩]

- Jezebel, “Photoshop of Horrors,” 17 March 2023, https://jezebel.com/tag/photoshop-of-horrors. [↩]

- menwritewomen, Twitter, 30 March 2023, https://twitter.com/menwritewomen. [↩]

- Anna_Mazz, Twitter, 31 May 2021, 27 March 2023, https://twitter.com/anna_mazz/status/1399413775871229958 [↩]

- Richard Nordquist, “Quotes About Close Reading,” ThoughtCo, 5 July 2019, 27 March 2023, https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-close-reading-1689758; My thanks to Merrill Schleier for her collaborative feminist close reading of this image. [↩]

- CourseHorse, “‘Feminist Lens’ Book Club: Grades 8-12,” 3 August 2022, https://coursehorse.com/nyc/classes/kids/kids-academic/kids-reading/-feminist-lens-book-club-grades-8-12. [↩]

- Amazon, “Amazon.com: Save up to 90% on rental, new, used, and digital textbooks,” 27 March 2023, https://www.amazon.com/gp/browse.html?rw_useCurrentProtocol=1&node=465600&ref_=bhp_brws_txt_stor. [↩]

- Goodreads, “About Goodreads,” 27 March 2023, https://www.goodreads.com/about/us. [↩]

- Michele White, “Touching Feeling Hands: Gender, Race, and Digital Devices,” Flow 29, no. 3, 7 December 2022, 24 March 2023, https://www.flowjournal.org/2022/12/touching-feeling-hands/. [↩]