Shudu and Her “Muses”: Stand-in Labor in Virtual Influencer Production

zizi li / University of California, Los Angeles

Digital visual effects, including 3D modeling and motion capture, are integral to virtual character production, used in creating virtual influencers/idols like Shudu, Lil Miquela, K/DA, and A-SOUL. Motion capture, abbreviated as mocap, is the act of capturing the movements of physical objects or people and recreating them virtually onto a digital character through simulation and alteration. Stand-in models and mocap performers are often invisible and poorly compensated. Mocap, as a technological medium that centers on the transference of original physical motion onto different objects, tends to de-emphasize the materiality of racialized and gendered bodies in construction of limitless characters in a post-racial, post-gender world. These tendencies can result in the race and labor of performers of color being erased and applied to white and racially ambiguous characters, as Tanine Allison (2015) has written regarding African American jazz singer Cab Calloway in Fleischer Studios Betty Boop cartoons in the 1930s, and Black tap dancer Savion Glover in Happy Feet (2006). This can also result in racially constructed virtual influencers with the seemingly diverse on-screen representation but without an equally diverse behind-the screen production team.

This column focuses on the usage of digital visual effects including motion capture, 3D modeling, and digital simulation in virtual influencer production using Shudu (2017-, UK) as the case study, attending specifically to her stand-in models and performers. Shudu joined the Internet in 2017 as a dark-skinned Black South African digital supermodel and fashion icon. She currently has 239K followers on Instagram, having worked with many fashion magazines and fashion/tech brands. She was created by white British fashion photographer and visual artist Cameron James Wilson, who established the digital model agency The Diigitals shortly after the launch of Shudu. The agency currently represents Shudu, six other virtual models—Galaxia, Brenn, Dagny, Koffi, J-YUNG, and Boyce—and four virtual brand ambassadors: Margot and Zhi, Kami, and AWA by Magnum.

Shudu is created using a combination of 3D modeling software Daz3D, Photoshop, and garment simulation program Clo3D. While it is possible to create Shudu fully in 3D, this option is limited by that many fashion designers do not have computer generated (CG) versions of their garments. The production of Shudu modeling fashion pieces often requires photoshoots with a real model wearing the physical garment before merging the stand-in model with Shudu together in 3D (Kane n.d.). The Diigitals website has a “muse” page featuring stand-in models and mocap performers who contribute to the creation of Shudu and her content, an uncommon practice since stand-in labor is most often concealed. From Alexsandrah Gondora’s write-up and interview, we learn she is a London-based model who became the first Shudu muse as she stood in as Shudu in a Vogue Australia editorial photoshoot. As seen in Figs 2b-c, Gondora has dots on her face for digitally mapping Shudu’s face onto Gondora’s posing.

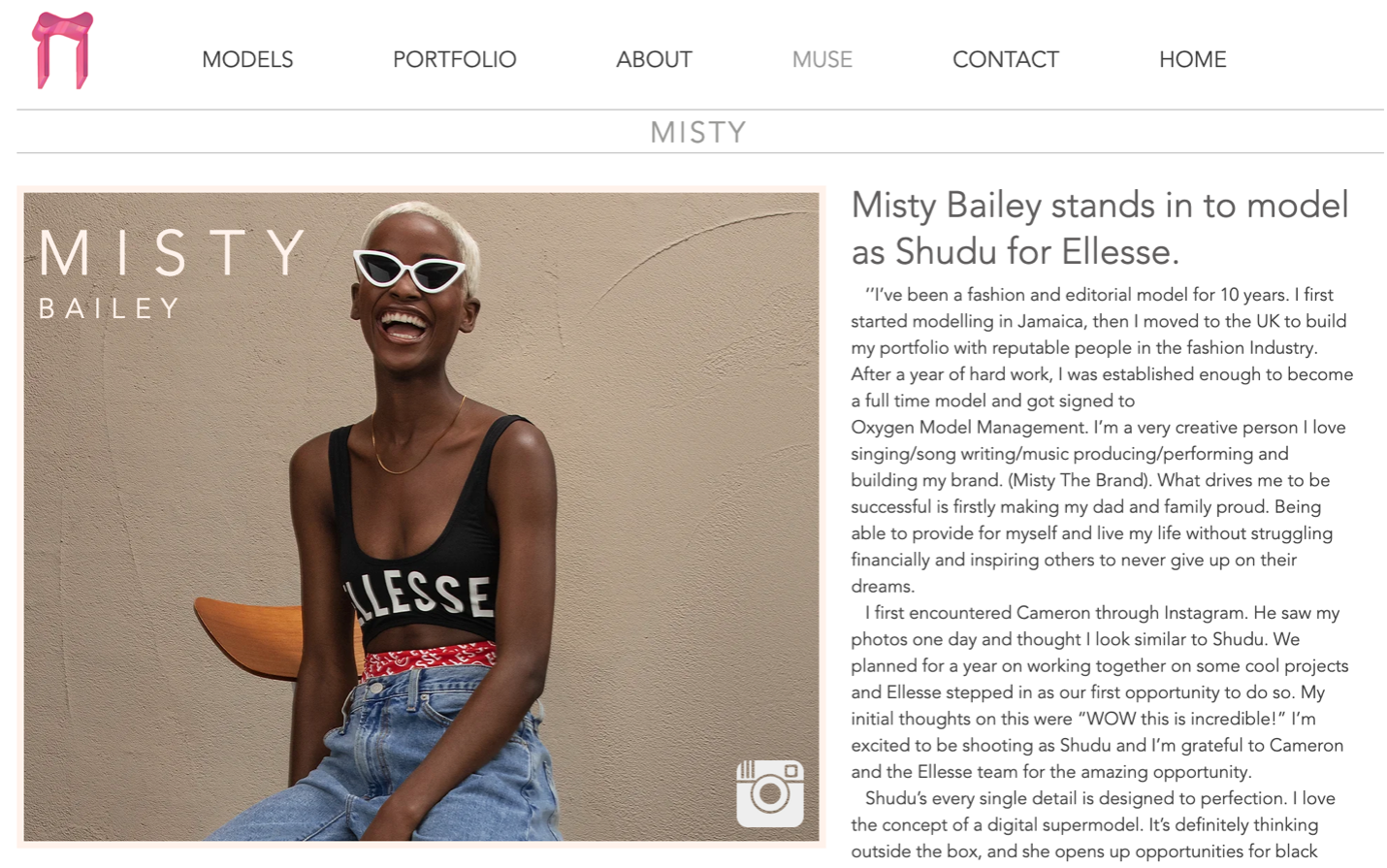

The production of Shudu at the 2019 British Academy of Film and Television Arts Awards Red Carpet as a real-time interactive hologram involved elaborate mocap production and layers of standing in. Shudu greeted and took photos with guests at the photo station while also doubled as an AI stylist, recommending more affordable versions of red-carpet attires to viewers through the chatbot. Misty Bailey [Fig 1], a London-based Jamaican model, stood in as Shudu getting ready on the day of the event [Fig 3a]. Janice Drummond, a Toronto-based model, performed a motion capture shoot as Shudu before the event with AI digital human company Quantum Capture to support the real-time rendering of Shudu as a hologram (Drummond n.d.; The Diigitals n.d.). As seen in Figs 3b-d, Drummond wore a whole-body motion capture suit with dots for her poses and movements to be captured and paired with Shudu’s still 3D model assets in Unreal game engine.

Figures 3a-d: The upper-left image is Shudu getting ready for the Red Carpet. The rest are behind-the-scenes photos from the motion capture session.

Figures 3a-d: The upper-left image is Shudu getting ready for the Red Carpet. The rest are behind-the-scenes photos from the motion capture session.

Since the identity of her creator was revealed as a young white man in this 2018 Harper’s Bazaar article, Shudu has received various critiques from Black women and women of color (Jackson 2018; Sobande 2021). Perhaps as a response to these criticisms, Wilson has since hired a Black British woman, Ama Badu, as Shudu’s writer and collaborated with a few Black women as stand-ins to perform Shudu’s poses, movements, and voices. Each of Shudu’s six muses of has an introduction page detailing their backstory, how they got involved in the production of Shudu, and their thoughts on the digital model industry. The pages acknowledge the name and work of these Black contributors to the viral making of Shudu. The narratives of these Black women are also officially approved marketing rhetoric that are used to establish the image and reputation of the Diigitals and Shudu.

Badu has been Shudu’s writer since 2019, composing answers to interviewers’ questions as Shudu, creating Shudu’s personality and story, and crafting an authentic voice consistent to Shudu’s character (Badu, n.d.). Badu co-creates key aspects of Shudu and has a certain power to contextualize Shudu and reshape how Shudu is being discussed. In an interview with BBC, Badu was asked how she is trying to change the fact that many Black women are upset about the concept of Shudu. She redirected the attention to issues faced by Black female models and proposed possibilities of changes. Having Badu taking over the narrative construction of Shudu provides a platform to further advance both of their careers while having a Black woman to oversee the story of a Black digital model. Yet Badu also becomes part of the PR strategy and shield to defend valid criticisms regarding the production and role of Shudu.

In an IGTV interview with Badu, Gondora also redirected the problem to the modeling industry. Gondora shared that Black models and models of color have consistently struggled in the modeling industry, and agencies mistreat Black models despite performatively support BLM on social media. Her biggest projects are not obtained through her agency but modeling as Shudu and the additional opportunities she gets through modeling as Shudu. Despite the cultural implication of a dark-skinned Black female model created by a white man, Gondora emphasized that Wilson always works with Black women in shoots for Shudu to ensure that the offers and deals he gains through Shudu materially benefit Black female models in the fashion and modeling industries. Bailey, in another IGTV interview with Badu, echoed the same appreciative sentiment regarding how Shudu can provide more opportunities for Black models with standard commercial rate. We also cannot deny that, compared to other supposedly diverse influencers like Miquela, Shudu exemplifies how the fame of a virtual influencer with marginalized identities can be leveraged to benefit real-life models, performers, and other creative workers with those identities.

However, I invite us to conceive the six Shudu muses as six contracted workers of the Diigitals to consider how the power dynamic might have influenced and shaped the narratives of these Black women. Officially approved workers’ accounts have always been used as a marketing tactics in opposition to critical voices. Here, Black women’s self-narratives are being mobilized as Wilson’s defense against his critics, mostly Black women, regarding the legitimate concerns of a white man imagining and creating an unrealistic and highly racialized and profitable CG influencer (Jackson 2018), and how Shudu is facilitating the imperialist, capitalist, patriarchal system that commodifies, consumes, and exploits Black women (Sobande 2021). The Internet has been a means for marginalized people to play, experiment, and build avatars that escape their realities. Yet Wilson’s defense (Product Innovation 2019) ultimately builds on the cyberspace’s power in allowing people to be free from their physical corporeality in a post-racial, post-identity rhetoric, an ideology often dangerously used to negate anti-racist and reparational practices.

Image Credits:

- Figure 1: A screenshot of the official webpage that introduces Misty Bailer as one of Shudu’s stand-in models. Source: The Diigitals.

- Figures 2a-c: The upper-left image is an editorial photo published in Vogue Australia. The upper-right and bottom images are behind-the-scenes photos. Source: The Diigitals.

- Figures 3a-d: The upper-left image is Shudu getting ready for the Red Carpet. The rest are behind-the-scenes photos from the motion capture session. Source: The Diigitals.

Allison, Tanine. 2015. “Blackface, Happy Feet: The Politics of Race in Motion Capture and Animation.” In Special Effects: New Histories, Theories, Contexts, edited by Dan North, Bob Rehak, and Michael Duffy, 200–224. BFI/Palgrave.

Badu, Ama. n.d. “The Diigitals Muses // Ama Badu.” Thediigitals. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.thediigitals.com/ama.

Drummond, Janice. n.d. “The Diigitals Muses // Janice.” Thediigitals. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://www.thediigitals.com/janice.

Jackson, Lauren Michele. 2018. “Shudu Gram Is a White Man’s Digital Projection of Real-Life Black Womanhood.” The New Yorker, May 4, 2018. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/shudu-gram-is-a-white-mans-digital-projection-of-real-life-black-womanhood.

Kane, Hannah. n.d. “Meet Shudu: The World’s First Digital Supermodel.” PHOENIX Magazine. Accessed December 3, 2022. https://www.phoenixmag.co.uk/article/meet-shudu-the-worlds-first-digital-supermodel/.

Product Innovation. 2019. FASHION MADE: Creator of Shudu, Cameron-James Wilson – The Man Behind The Model. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dHgwUf-2nOU.

Sobande, Francesca. 2021. “Spectacularized and Branded Digital (Re)Presentations of Black People and Blackness.” Television & New Media 22 (2): 131–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476420983745.

The Diigitals. n.d. “The Diigitals BAFTA.” Thediigitals. Accessed December 7, 2022. https://www.thediigitals.com/bafta.