Radio country

Morgan Bimm / ST. FRANCIS XAVIER UNIVERSITY

I’ve been thinking a lot about radio.

Ever since moving to rural Nova Scotia, radio is everywhere. I bought a used pickup truck from an older local and was too charmed by the pre-programmed stations to change them. The first month of my life here, my drives were soundtracked almost exclusively by Acadian folk and country broadcast out of Chéticamp, Cape Breton. Sometimes I would accidentally tune into weekly bingo on the local FM station. And, inevitably, I listened to the CBC.

When I was making plans to drive back to Toronto for winter break, I laughed when a colleague suggested I could listen to the CBC for all 1800 kilometers. But slowed down to a crawl in a snowstorm along the 401, there was something undeniably comforting about scrolling through local stations until I stumbled across that unmistakable jingle, spread reliably from coast to coast via our national broadcaster.

Canada is — for better or worse — a radio country (Alia 2004, 78).

ECHO

A tweet from a Toronto-based Twitter pal reads, “i just heard a land acknowledgement on kiss fm [sic] and they put the echoey effect on ‘mississaugas of the new credit’” (jkac 2023). Despite the relatively recent adoption of land acknowledgements by state institutions, universities, and other arbiters of moral legitimacy, these practices have become an integral part of the Canadian psyche (Wark 2021). Indigenous (and non-Indigenous) critiques of land acknowledgements often note that these statements function as strictly symbolic stand-ins for meaningful, systemic change and are fundamentally disconnected from actual Indigenous people. Rather, according to Anishinaabe writer Armand Garnet Ruffo, land acknowledgements are about “settlers talking to themselves to assuage their guilt” (Robinson et al. 2019, 26).

In 2016, as part of te wiki o te reo (Māori language week), Radio New Zealand reporters began signing off reports in te reo Māori, the Māori language. Reactions varied widely. Some listeners complained about the “over-Māorification” of the station, many expressed gratitude, and the Māori wife of one RNZ reporter noted that her Pākehā (white) husband was able to champion te reo in a way that felt “impossible for [her] to do.” The rote inclusion of land acknowledgements on a Canadian Top 40 station and Pākehā reporters signing off RNZ broadcasts in te reo Māori are notably different approaches to decolonizing radio, however both fall embarrassingly short of making room for Indigenous broadcasters or Indigenous culture itself.

Settler radio is full of echoes, enhanced with more echo.

SILENCE

The technology of radio itself is intimately bound up with Canadian nation-building and settler colonial imaginaries. The CBC got its unofficial start in the 1920s as a service on the Canadian National Railway (CNR), itself a beacon of “technological nationalism” (Charland 1986). In the pages of CNR Magazine, a 1931 ad for Burgess radio batteries touted radio as “a marvel of the age” (Alia 2004, 79). The ad featured two Inuk children in the Baffin Island community of Pond Inlet, listening to headphones and flanked by copy that boasted of “breaking the centuries-old silence of the Arctic” (ibid).

Settler logics of terra nullius — empty land — cannot imagine a pre-colonial soundscape that wouldn’t be improved by radio technology. This might also explain the spotty historical records and ongoing archiving of Indigenous radio networks and Indigenous-run stations, which many radio and sound scholars are finally considering alongside those settler histories that understand radio as a “civilizing technology” and a straightforward extension of settler benevolence (Wark 2021, 202). Both radio and rail were imagined to be traversing space that was uncharted and silent.

NONDESCRIPT

As part of her MFA thesis, multimedia artist Kristy Boyce (2019) painted a vintage radio white and programmed a Featherwing Musicmaker to play “a constant drone of racist quotes” from Canada’s first prime minister, John A. MacDonald. The object, explains Boyce, was borne from her frustrating attempts to effectively communicate the true nature of historical figures like MacDonald, and the violent acts they perpetuated. Colonial Radio has multiple tracks that the user can turn the dial to and from, all of them featuring a soft Scottish brogue saying abhorrent things, many relating to the systemic genocide of Indigenous people.

The nondescriptness of particular voices and bodies has everything to do with whiteness, but there’s something specific to Canadian whiteness that seems to work overtime in this particular regard. When Stanley Kubrick set out to find the perfect voice for HAL, the disembodied ship in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), CBC radio drama veteran Douglas Rain was the director’s top choice. According to Kubrick, Rain’s voice was “neither patronising, nor [was] it intimidating, nor [was] it pompous, over dramatic or actorish.” Instead, Rain supplied a voice that had the quality of coming from “nowhere” — a quality that sociologist Michael Follert (2022) argues is fairly consistent with the inoffensiveness of Canadian English’s reputation worldwide.

I teach my students about Canadian nationalism by watching Jeff Douglas perform in iconic Molson beer commercials, then drive home listening to Jeff Douglas’ rounded Nova Scotian vowels on the CBC and think about whose voices get to be admirably and utterly nondescript.

DISEMBODIED

If radio is “an essential social and political tool” (Alia 2004, 80), then it is also a deeply weird one, grounded in the normalization of disembodied or acousmatic sound. Marshall McLuhan, rock star of Canadian media philosophy, once noted the power of audio “to make present the absent thing” (1964, 69). Follert (2022) refers to this particular quality of radio as “eerie” and charts, in his history of Canadian radio dramas, all of the ways in which this particular eeriness is tied to settler alienation and anxieties.

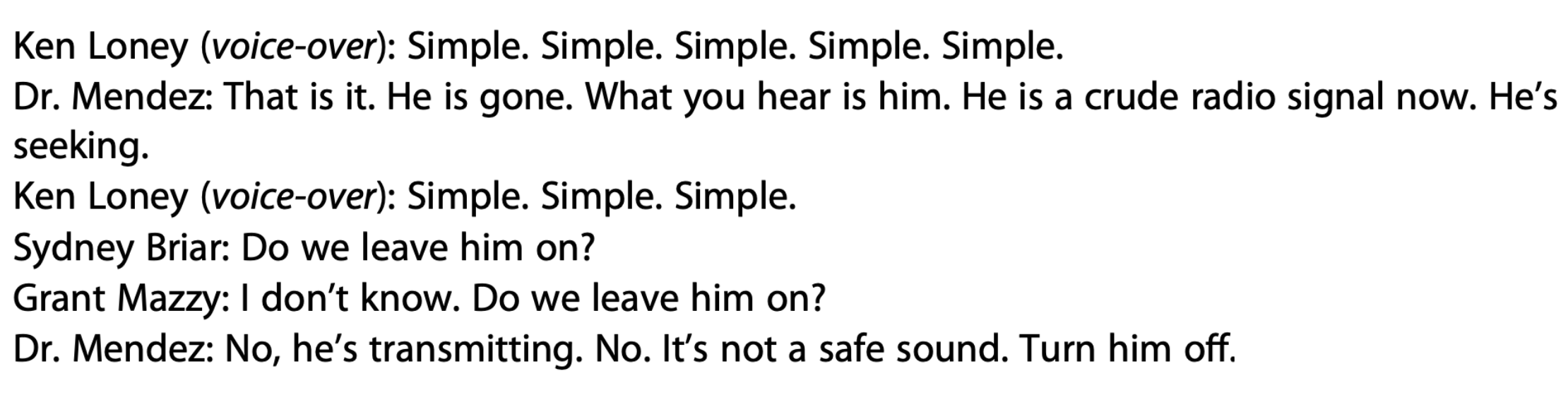

Pontypool (2009) was a Canadian radio play that focuses on the spread of a mysterious virus in rural Southern Ontario that causes its victims to lose control of their speech. The virus is passed on by words (which means the local radio station is complicit) and eventually “produces an effect of echolalia in its victims, who devolve into a mindless state repeating words” (Follert 2022, 11). The eeriness of this particular story, suggests Follert, lies in the idea of a voice that fails to signify. When the local weather reporter succombs, his stammering is broadcast over the radio within the radio play, producing a kind of matryoshka doll of radio-mediated heebie jeebies.

There’s no echo effect being used here, but I can’t help but think of the mindless repetition of land acknowledgements. The continuous presence of the eerie, disembodied voice in Canadian radio drama, argues Follert, functions as an extension of settlers’ alienated relation to place in “a country that comes into existence largely through a surfeit of technological mediation” (2022, 16). It connects us even as it reinforces this alienation, shoring up the persistent myth of settler futurity even as it mediates our guilt.

So I drive my truck. I look out at the ocean. I think about how easy it was for me as a young settler scholar to orchestrate a cross-country move, and how that is its own kind of echo. I think about these things, even though there’s nothing in particular that compels me to do so beyond my own curiosity. I listen to the CBC and occasionally feel weird about it.

But Canada is — for better or worse — a radio country.

Image Credits:

- Kristy Boyce’s Colonial Radio (2019), exhibited at the Toronto Media Arts Centre.

- Tweet from @jkac, January 2023 (author’s screen grab).

- Kristy Boyce’s Colonial Radio (2019), exhibited at the Toronto Media Arts Centre.

- An excerpt from CBC’s Pontypool (Burgess 2015, 51) (author’s screen grab).

Alia, Valerie. “Indigenous Radio in Canada.” More Than a Music Box: Radio Cultures and Communities in a Multi-Media World, edited by Andrew Crisell, Berghahn Books, 2004, pp. 77-94.

Boyce, Kristy. The White People Problem: Experiments in the Reverse Gaze. 2019. Ontario College of Art and Design, MFA thesis.

Burgess, Tony. Pontypool. Toronto: Playwrights Canada Press, 2015.

Charland, Maurice. “Technological Nationalism.” Canadian Journal of Political and Social Theory, vol. 10, no. 1-2, 1986, pp. 196–220.

Follert, Michael. “Evocations of the Eerie: The Acousmatic Voice in Canadian Radio Drama.” Sound Studies, doi: 10.1080/20551940.2022.2158677.

McLuhan, Marshall. “Radio: The Tribal Drum.” AV Communication Review, vol. 12, no. 2, 1964, pp. 133-145.

Robinson, Dylan, Kanonhsyonne Janice C. Hill, Armand Garnet Ruffo, Selena Couture, and Lisa Cooke Ravensbergen. “Rethinking the Practice and Performance of Indigenous Land Acknowledgement.” Canadian Theatre Review, vol. 177, pp. 20-30.

Wark, Joe. “Land Acknowledgements in the Academy: Refusing the Settler Myth.” Curriculum Inquiry, vol. 51, no. 2, 2021, pp. 191-209.