Mediating Emergency in Moments of Campus Tragedy

Elizabeth Ellcessor / University of Virginia

While I slept on November 13, 2022, my phone received 26 emergency alerts from the University of Virginia. Scrolling through them in reverse chronological order, I realized that there had been a shooting, and that the campus and region remained in crisis. That night, a student opened fire inside a bus returning from a field trip, killing three— Devan Chandler, Lavel Davis Jr., and D’Sean Perry—and injuring two. That morning, the shooter remained at large, leading to the closure of local schools and businesses amidst a regional manhunt before an arrest was made.

These events at the University of Virginia are, sadly, not anomalous. Most recently, on February 13, 2023, Michigan State University was targeted by a gunman who killed three students—Arielle Anderson, Brian Fraser, and Alexandria Verner—and injured five before turning the gun on himself.

These tragic events may not seem at first to be a matter of media studies. However, media systems such as emergency alerts help to construct the affective and informational environments of emergency. What we know, how we feel, and what we do are often shaped by mediated presentations of relevant information. The work of media studies in an era of active shooters, then, might be to consider these messages in terms of their production and dissemination; by understanding them not as neutral information but as constructed and negotiated texts, we may be able to more closely consider and take action concerning the pervasive but little-discussed infrastructures and institutions of campus safety, emergency management, and policing.

Such is my goal in this short piece. I draw on interview and participatory research with campus emergency managers and student focus groups, applying insights from this prior research to the specific events at UVA, and with reference to MSU.

Producing Emergency Alerts

Since the 1990 Jeanne Clery Act, colleges and universities have been required to issue “timely warnings” via email about specific crimes committed within the established geography of the campus. Secondly, following the 2007 mass shooting at Virginia Tech, the Clery Act was amended to require notification of all members of the campus community about a “significant emergency or dangerous situation occurring on the campus that involves an immediate threat to the health or safety of students or employees” (20 U.S. Code § 1092, Section f1Ji).

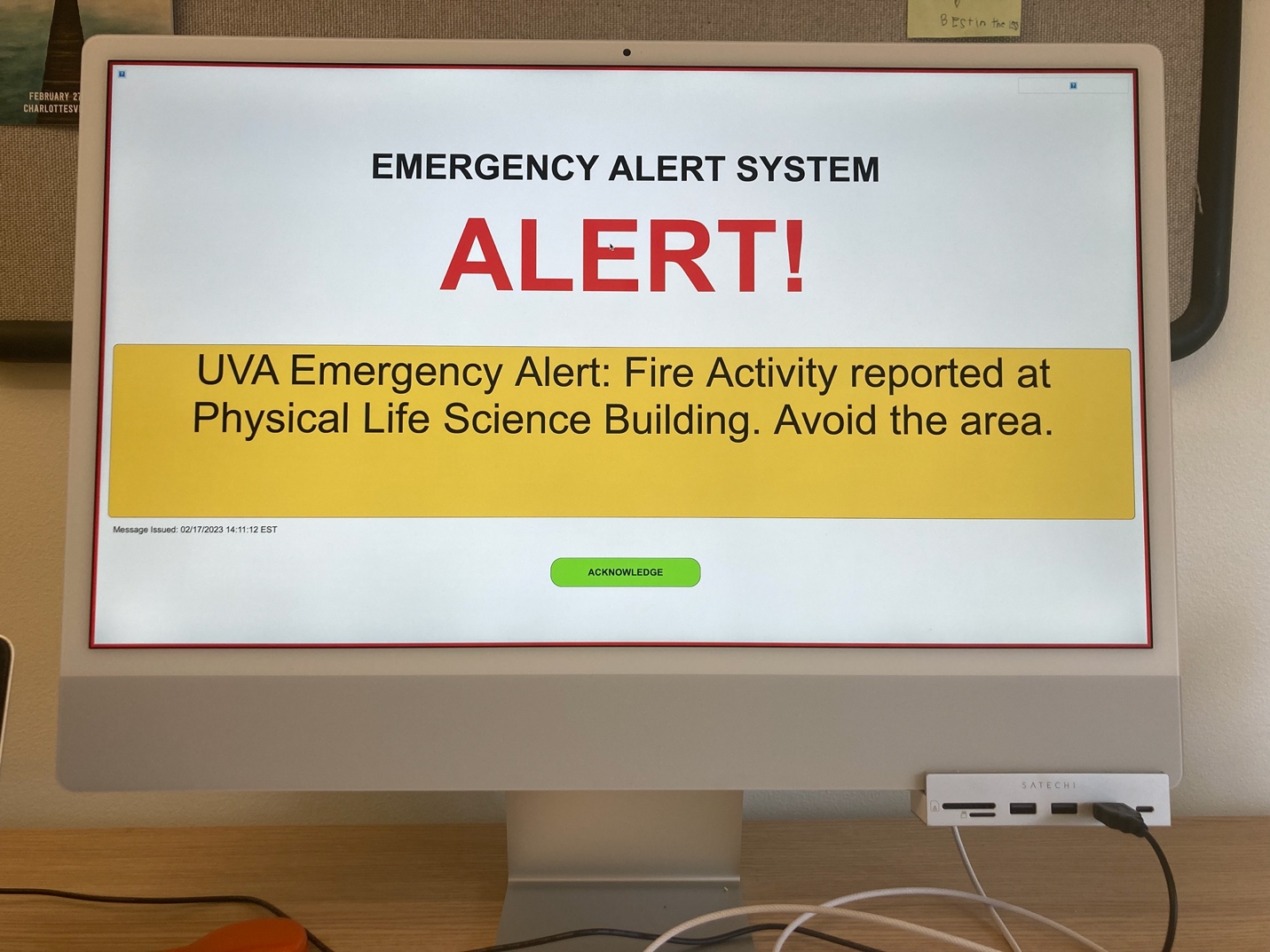

Emergency notifications are likely, in recent years, to be sent via text message as well as email, and to spread across campuses via a “total alerting environment” that may encompass outdoor speakers, digital signage overrides, desktop overrides on network computers, LED marquees, and dedicated apps and push notifications. Emergency notifications are also increasingly likely to offer an opt-in notification system for community members “outside” of the immediate university geography, such as professors who live across town or students’ parents who live across the country.

The implementation of campus alerting can vary; sometimes this is the purview of an office of emergency management, sometimes it falls under the decision-making powers of the campus police, and sometimes others, such as the Title IX office, Dean of Students, or other administrative units may be consulted. For instance, notifications may be initiated by campus police who offer “boots on the ground,” first-hand perspectives, but then vetted or amended by others prior to release.

Awareness of who is sending alerts and the decisions they are empowered to make is critical to thinking about the production of emergency notifications as a form of media work that involves crafting persuasive messages for an audience. Determinations of what constitutes an emergency “can get very subjective,” in the words of one campus emergency management staffer, meaning that alerts generally prioritize the most “obvious” emergencies, such as floods, explosions, or active shooters.

Constructing Emergency Notifications

Once a decision has been made to send emergency notifications, messaging becomes a site of variable decision-making and communicative strategy. There are best practices for emergency alerts, which indicate that “complete” messages with information about the “message source, hazard identification, hazard location, timeframe, and guidance” (Doermann et al 2021, 818). are the most successful in producing desired behavior by recipients. Similarly, a long-time campus emergency manager with experience in active shooter situations explained that their alerts always include three pieces of information: what happened, where it happened, and what the recipients should do next.

With these guidelines in mind, we might compare two emergency alerts, one sent by UVA and one sent by MSU:

UVA Alert: ACTIVE ATTACKER firearm reported in area of Culbreth Road. RUN HIDE FIGHT (11/13/22, 10:43pm ET)

MSU Police report shots fired incident occurring on or near the East Lansing campus. Secure-in-Place immediately. Run, Hide, Fight. Run means evacuate away from danger if you can do so safely, Hide means to secure-in-place, and Fight means protect yourself if no other option. Monitor alert.msu.edu for information. (2/13/23, 8:31:52pm ET)

Both alerts reference the federal “run, hide, fight” guidance for active shooter situations. However, the UVA alert lacked explanation and the used all capital letters, which conveyed a frightening urgency but offered little guidance. Based on what we know from research in emergency management and communications, the UVA alert was practically assured to produce greater panic and lesser effectiveness, as students and community members sought to parse the message and pool information. The MSU alert, by including options for immediately access more information, may have reduced the panicked search for reliable information among its community.

Beyond the stylistic delivery of emergency messages and the quantity of information offered, the production of emergency notifications ought to be informed by the variety of needs among the target audience. For instance, many emergency managers told me about deliberately avoiding metaphors in order to communicate as clearly as possible with students whose first language may not be English.

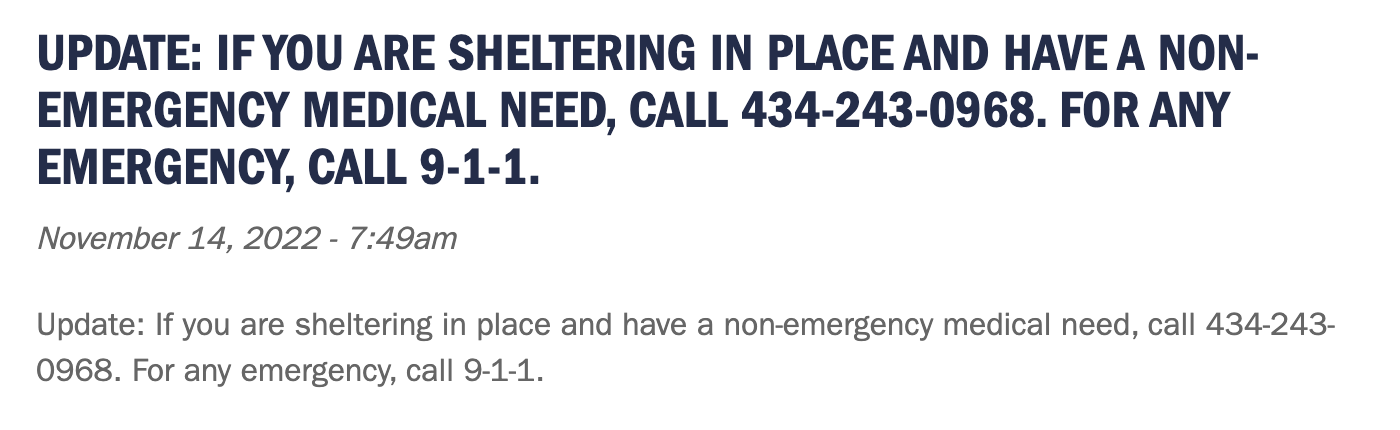

Additionally, the production of emergency alerts must include consideration of those with specific needs, including disabled or chronically ill people; nearly twelve hours after issuing the alert to shelter-in-place, UVA finally sent an alert instructing the community how they might reach out if they had a non-emergency medical need. By this point, some students had been locked down in libraries or laboratories overnight with no way to access food, water, or necessary medications.

The belated consideration of the needs of community members was indicative of an approach to alerting that prioritized communication about law enforcement needs and activities over the informational and material needs of the university community.

Community Reception of Emergency Alerts

In UVA’s messages, community concerns were addressed more as time went on, with a message at 9:14am on the morning of November 14th concluding “Please stay safe, thank you for your patience and understanding.” As I have argued elsewhere, producing and disseminating emergency alerts is a form of media work, involving decisions about messaging and audiences (2022). Approached from this perspective, this alert reads almost as an apology for earlier messages and their affective effects, evidence of growing awareness that authorities’ decisions regarding information, tone, and inclusion all have consequences in terms of how a given public receives and responds to emergency alerts.

There is ample evidence that upon receiving emergency alerts, people, including college students, usually seek confirmation by looking at social media, news reports, and the behavior of those around them. There is also evidence of gendered differences in feelings and behavior (Hasinoff & Krueger 2020, 21) following alerts, and increased feelings of vulnerability among disabled or chronically ill people who have less confidence that their needs will be addressed in emergency situations (Ladau 2020). In short: no amount of curation of emergency messaging can fully control the actions of the alert public that they address. There is room for negotiation and refusal in the reception of emergency alerts, particularly in circumstance in which there is little trust in the authority issuing the alert.

Furthermore, the institutional and geographical limits of university emergency alerting can impede their utility. In the case of the UVA shootings, while university community members were informed, there was no attempt to coordinate with local authorities to issue alerts to the larger city, county, or region. Thus, elementary schoolers in Albemarle County boarded school buses only to have them turn around as officials belatedly learned of an active shooter on the loose in the region and made the decision to close schools. Community members outside the university balked at this decision, and the lack of inter-agency coordination that it seemed to indicate. The trust in university police, city police, and state law enforcement was weakened by a serious of decisions in which the specific policies of campus safety seemed to prioritize some people’s safety over others.

The analysis of campus emergency alerts in this piece is only a start. However, I offer it as a model for any of us interested in considering how our colleges and universities attempt to use media to control and contain issues of safety, risk, and danger.

Image Credits:

- The historical Rotunda on the Grounds of the University of Virginia (University of Virginia Communications).

- A ”desktop override” emergency alert on the author’s computer screen in a campus office (author’s personal collection).

- A screenshot from UVA’s Alert Archive, showing the message sent about non-emergency medical needs.

Doermann, Jessica L., Erica D. Kuligowski, and James Milke. “From Social Science Research to Engineering Practice: Development of a Short Message Creation Tool for Wildfire Emergencies,” Fire Technology 57 (2021): 818. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10694-020-01008-7.

Ellcessor, Elizabeth. In Case of Emergency: How Technologies Mediate Crisis and Normalize Inequality. New York, NY: New York University Press, 2022.

Hasinoff, Amy A., and Patrick M. Krueger. “Warning: Notifications about Crime on Campus May Have Unwanted Effects.” International Journal of Communication 14 (January 2020).

Ladau , Emily. “As a Disabled Person, I’m Afraid I May Not Be Deemed Worth Saving from the Coronavirus,” HuffPost, March 25, 2020.