Imma with her im/material boxes

Zizi Li / University of California, Los Angeles

Virtual influencers—social media-native personas who exist virtually with no offline referent (Berryman et al. 2021)—are increasingly popular nowadays. They have been widely embraced in Asia and South America, with notable examples including Lu de Magalu (2003-, Brazil), Hatsune Miku (2007-, Japan), and the focus of this piece, Imma (2018-, Japan), introduced by Tokyo-based Japanese virtual human company Aww Inc.. Imma is currently present on Instagram, TikTok, Twitter, Zepeto, Discord, and RED. Rocking her bubble-gum pink hair, Imma has collaborated with numerous brands and participated in TikTok challenges, gameplays, and NFT designs. Esperanza Miyake (2022) proposes “semiotic (im)materiality” to capture the relationship between immaterial signifier and immaterial signified when theorizing virtual influencers. I am drawn to how Imma has been visually juxtaposed to varying im/material boxes in her media content, and how these juxtapositions add to her im/materiality as a virtual influencer exist in phygital spaces and built from computer-generated (CG) and real images.

Imma released a close-up image featuring half of her face on November 4, 2018 [Fig 1], continuing a series of images posted in October that comprised close-ups of varying parts of her face. Unlike previous images that show her CGI realism by highlighting her individual eyelashes and visible eye socket, this post juxtaposes the realness of her features with a digital grid on her cheek and 3D blue boxes floating out from the grid. Such juxtaposition feeds into the spectacle of Imma’s fluidity in between physical and digital experiences. I contend that the digital fragmentation here as signified by the abstract grid and boxes furthers both the gendered fragmentation and the digital-Orientalism of Imma’s body (Miyake 2022). The close-up imagery frames and objectifies Imma’s realist beauty, with her eye and lip also serving as signifiers of Asian Otherness and Japanese raciality for the Western spectators. The digital grid and boxes visually feed into the long-standing techno-Orientalist fascination and fear of Japanese technology (Roh et al. 2015), and the imaginary of Asian women as perfectly beautiful, submissive fembots whose othered bodies are constantly being prosumed. What do these digital grids and boxes refer to? Perhaps they are the pixels that composite Imma’s social media imageries or vertices in Imma’s polygonal model. Perhaps they are beautified infrastructures behind the 3D scanning, facial capture, and photo-realistic modeling.

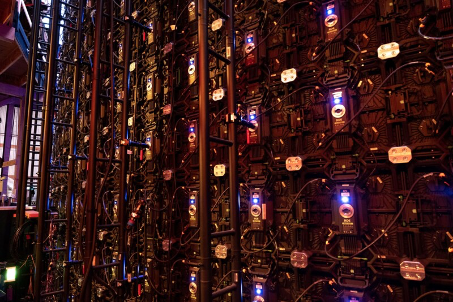

Fast-forward to 2020, Imma partnered with the Swedish furniture retailer IKEA to promote its new retail location in Harajuku, a district in Tokyo known for shopping, dining, and Japanese street fashion. Imma moved to a physical storefront apartment in IKEA Harajuku for three days, and continue to do her everyday activities like cooking, reading books, doing Yoga, and bedtime routine. They installed her room with physical furniture pieces and LED screens, the latter’s ability to adapt color temperature in real time made possible Imma’s phygital appearance. Passers-by could see Imma living her life in this literal apartment box through the shop windows. People could tune in to her 72-hour Livestream on YouTube and IKEA.com. Slices of her life were also updated on her social media in real time. In this video documentation, spectators are immersed in the apartment box with Imma for half of the time, observing her as she starts her day with a morning stretch on her bed and partaking in mundane tasks like watering plants, vacuuming, and streaming movies. For the remaining time, viewers’ interactions with Imma are mediated through various digital boxes, from smartphone screens to Instagram images, from TikTok videos to text boxes. The video’s editing emphasizes Imma’s fluid alteration in between the physical and the digital space. What it does not indicate is how Imma’s seamless im/material fluidity is enabled by pixels and vertices, and mediated by a room of grid-like LED walls composed of hundreds of individual box-shaped LED screens interconnected with chords [Fig 3]. Performing Imma’s seamless im/materiality is extremely resource intensive, simultaneously mobilizing the materiality of LED walls, the production labor behind the planning and technical execution of this installation, and a huge amount of electricity required to maintain the three-day live operation.

Fig 2 shows how Imma was in a box-like living space on the ground floor of the IKEA store. There are two campaign posters to the right of her box, behind which we see the common retail set-up with stacks of boxes and products on display. Living units are designed as containers of our bodies, belongings, and activities, like how retail boxes store commercial goods. Imma curated the room to reflect her individual taste and lifestyle whereas the typical IKEA room display appeals to a wider range of customers with less individualized design. According to Christopher Travers of Virtual Humans, “happiness at home” was what the IKEA x Imma collaboration sought to explore. This notion is consistent with the longstanding pursuit of joy, a highly immaterial state, through extremely physical and affective tasks of home management including decluttering, tidying up, and reorganization, further popularized by Japanese tidying expert Marie Kondo among others in the past decade. I feel akin to Imma since both our lives are contained in and organized by boxes. Both of us live in a tiny box-like apartment and experience our time-space simultaneously in between the physical world and the social media environment. Like Imma getting a wardrobe with a built-in desk to accommodate her multifold needs in a small bedroom, I turned to containers and furniture pieces as solutions to home management and personalization. Like Imma in this post, I used brown cardboard boxes to contain, protect, and transport my belongings during my recent move. We also share the love toward fashion, art, and film.

On January 29, 2021, Imma’s collaboration with The Drop—Amazon Fashion’s partnership with influencers to sell limited edition collections—was launched, featuring eight physical fashion items Imma designed with 3D computer graphics. The accompanying concept film Tokyo Chaos emphasizes Imma’s im/material fluidity by editing together footage of Imma traversing across real [Fig 4c], CG [Fig 4a], and animated [Fig 4b] worlds. Fig 4a shows Imma in a CG cityscape, standing in a flower field and looking at high-rises with LED billboards playing images that mostly feature her fragmented body parts, especially eyes and pink hair. This instance exemplifies how digital fragmentation—here as box-like urban screens—enhances the prosumption of alienated fragmentation of gendered and racialized bodies (a point discussed earlier regarding Fig 1). Fig 4c captures Imma sitting down and holding a small box amongst stacks of Amazon cardboard packages in a box-like delivery van that is unrealistically loosely packed. The two young men at the peripheral, each wearing a t-shirt from Imma’s collection, close the door before the van drives out to deliver these orders. If the virtual city screens and the fantastical animation of Imma emphasize her immateriality, this final appearance of Imma interacting with physical delivery materials highlights her materiality while obscuring highly exploitative and subhuman material conditions experienced by Amazon delivery workers and other manufacturing and logistical workers that enable the flourishing e-commerce industry.

Indeed, all three media texts discussed in this piece offer us an Imma that seamlessly co-exists in the physical and digital worlds and is visually juxtaposed with varying literal and figurative boxes as stand-ins of operating units and infrastructural objects. In an era marked by virtual engagement, it is even more important for us to attend to the hidden extraction of (im)material labor, infrastructure, and resources continued and/or enabled by digital innovations.

Image Credits:

- Figure 1. One of the early images of Imma released on Instagram in 2018.

- Figure 2. A screenshot from the video documentation of Imma’s installation with IKEA Harajuku.

- Figure 3. The back of LED panels. Source: fxguide.

- Figures 4a, b, and c. Screenshots from Imma x Amazon The Drop’s concept film Tokyo Chaos.

Berryman, Rachel, Crystal Abidin, and Tama Leaver. 2021. “A Topography of Virtual Influencers.” AoIR Selected Papers of Internet Research. https://doi.org/10.5210/spir.v2021i0.12145.

Miyake, Esperanza. 2022. “I Am a Virtual Girl from Tokyo: Virtual Influencers, Digital-Orientalism and the (Im)Materiality of Race and Gender.” Journal of Consumer Culture. https://doi.org/10.1177/14695405221117195.

Roh, David S., Betsy Huang, and Greta A. Niu. 2015. “Technologizing Orientalism: An Introduction.” In Techno-Orientalism: Imagining Asia in Speculative Fiction, History, and Media, edited by David S. Roh, Besty Huang, and Greta A. Niu., 1-19. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.