Over*Flow: “It’s not dark humor if it’s not your trauma – you’re just bad people”: The exploitative nature of TikTok meme cultures

Moa Eriksson Krutrök / UmeA University, Sweden

Social media can potentially provide important spaces for individuals to find social support in mourning, but how do meme cultures potentially make or break these platforms as safe spaces for sharing grief?”

We all know the internet is a dumpster-fire raging with misogyny, white supremacy, and extremism. Trolling and memeing have been a cornerstone of the internet culture as we know of it today, and Whitney Phillips has been one of the most well-read scholars exploring this phenomenon in her book This is why we can’t have nice things (2015). [1] But social media can also provide individuals with spaces where they are allowed to share vulnerability, existential issues, and find peer-support in times of need, which can have important mental health effects. [2] These communities can also create a sense of stability and security for people in vulnerable positions, [3] in what scholars have referred to as “digital affect cultures.” [4] In a recent study, I explored the ways TikTok is used by mourners in sharing their grief and support each other in times of need. [5] Turns out, TikTok isn’t just a space for dance videos, which non-users still seem to believe.

But TikTok is a platform heavily based on a meme culture, where content is recontextualized through an ever-lasting chain of remixes. The interpretation of memes is, in fact, derived from “their exploitation of context,” [6] and in Dawkins’ [7] original coinage of the term “meme”, he was especially concerned with how cultural contexts moved between individuals. As the internet has evolved, where new platforms have popped up, and their features change, so do memes themselves. Through the platform affordances of, for example, TikTok, Abidin [8] has announced an “audial turn” of memes, where memes have come to include the use of recordings, sounds and music, which has become the “driving template and organizing principle” of TikTok itself.

So, what happens when the context that is being exploited is trauma-based? Recently, I liked a TikTok that brought me to tears. Of course, partly why I’m seeing this content is because I, myself, am dealing with mental health issues, and my “For you”-page is more or less constantly flooded with content about depression, PTSD (or c-PTSD), childhood trauma or therapy. The TikTok was by a user I hadn’t come across before, named @sunnybrooke14. She sat in her car and addressed the camera, teary-eyed, saying: “I got some big news today, but my mom is dead, so can you guys to pretend to be my mom for a minute?” [9] She had acquired a job in the same ER that her mother had worked in for about 16 years, and she continued by saying: “and I’m starting off in the exact same position you were in when you started nursing.” It was a heartfelt, honest, and emotionally wrecking story that is not at all uncommon on this side of TikTok. Sharing these forms of emotional intimacy with others has become an internet vernacular [10] rather than an abnormality in this space.

But I was surprised – and apparently naive – when less than a week later she took to TikTok to respond to the massive number of reactions that this original video had sparked. As this video had gone viral, it for sure had not gone viral simply on the side of TikTok I frequently inhabit. Instead, this video had been endlessly dueted by dudes in their 20s and 30s who seemed to have a fun time acting out as the role of the mother. I.e., pretending to be dead.

Grief on social media is hard. While grief norms in the general society can mean that individuals in mourning should process their grief in private, [11] socially mediated forms of grief place them, rather, out in the open for anyone to see. And unfortunately to scrutinize. For example, Abidin [12] has explored how, what she calls, “digital grief etiquette”, shapes ideas about what mourning should look like, and who is allowed to share them. When celebrities die, we have a myriad of ideas concerning who should really be mourning them, which has been referred to as “grief policing” online. [13] But what happens when grief is exploited as memes in a meme culture where anything is up for grabs as the butt of the joke?

While writing this piece, there is a massive amount of content being shared on TikTok covering another form of grief. The grief of war. TikTok has become one of the most essential platforms for sharing witness accounts from the Ukraine. But we are additionally seeing an exploitation of older, now resurfaced, videos and sounds being used again and again in the current situation, either pretending to be, or being interpreted as, current footage. [14] As already said by Stokel-Walker, “the platform’s design and algorithm prove ideal for the messiness of war—but a nightmare for the truth.” [15]

In addressing the video with the nurse who lost her mom, @sunnybrooke14 called these duets out, saying: “Five and a half thousand duets on this video and probably five thousand of them are of people making the exact same joke, so just for funsies and because I kind of hope it makes you guys feel like shit, here is my mom”, showing images of her mom in the very last month of her life, being incredibly weak but still attempting to smile and be present for her grandchild on her death bed, “she dedicated her whole life to saving other peoples’ lives, and this is how she got to go out”. By showing these sides of the story, the very last instances of her mother’s life, @sunnybrooke14 was clearly trying to make the jokers sorry for their actions.

When a track from the debut album WASTEISOLATION by the band Black Dresses went viral by being used as musical track for a myriad of TikToks showcasing users cosplaying, the band attempted to stop these types of videos using the sound, citing that it was a song about “our experiences with childhood sexual assault”. As a result, they experienced “extended invasion of privacy and harassment” and a “hurtful and frightening behavior” from TikTok users, and the band eventually decided to disband. [16] This further shows that exploiting trauma contexts as a memeified form of interacting on TikTok has potential to become detrimental for the original creators.

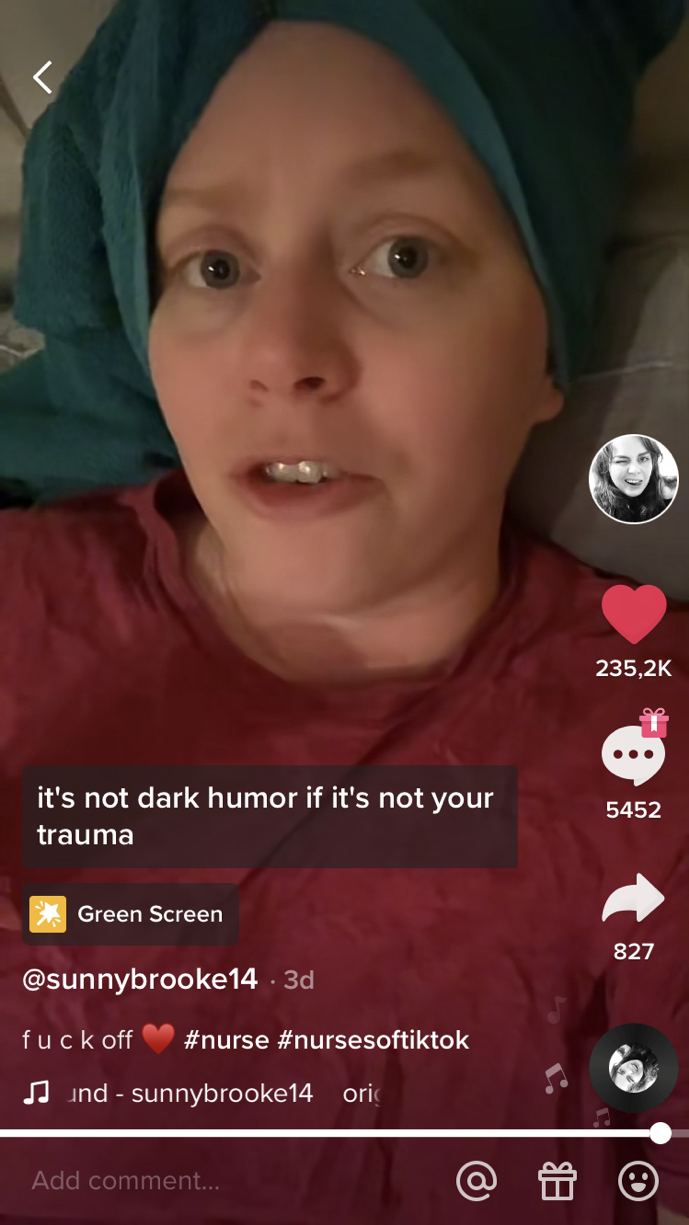

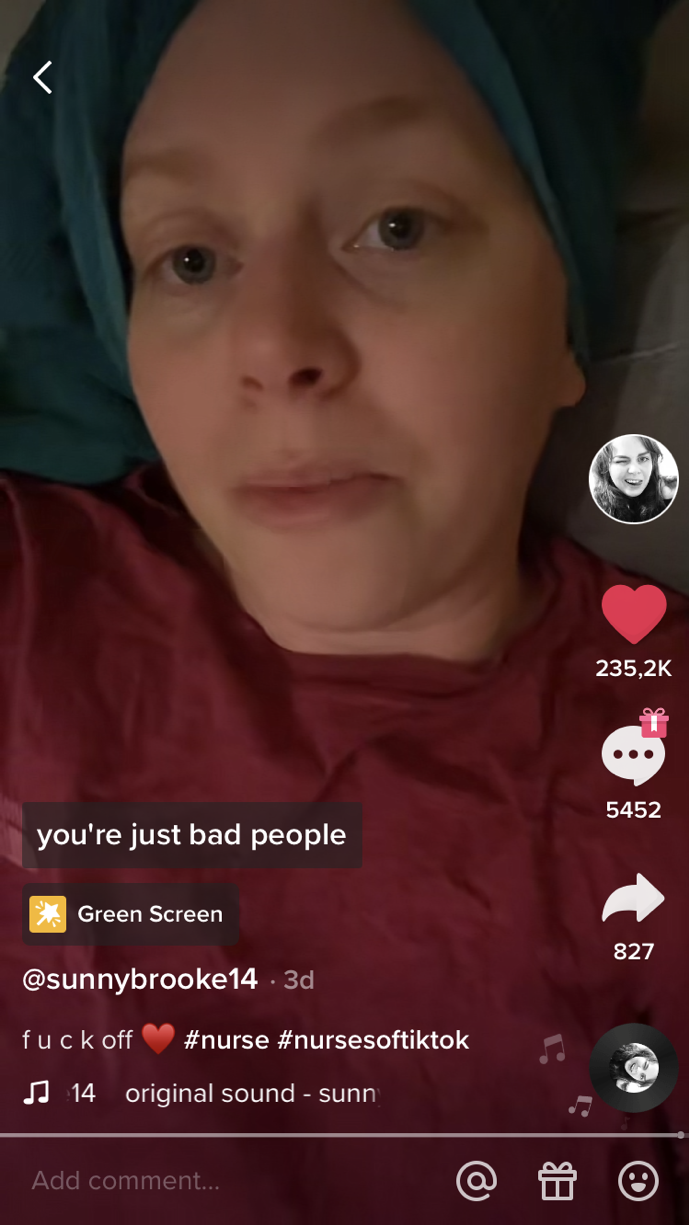

The last words of the reaction video by @sunnybrooke14, one week after the original video, was what set me, and her whole comment section, off the most: “It’s not dark humor if it’s not your trauma – you’re just bad people”. My side of TikTok is an honest and open space, where mental health issues are constantly disclosed, but also honored. But because TikTok is such a vast and fragmented space, the TikToks made for one specific group may be exploited as memes in other contexts. These memefied responses are not considerate of such safe spaces that alt-TikTok communities attempt to create in unison. Then, these communities become unsafe, and their users additionally exploited. Just for the laughs.

This safe space might just be imaginary. In fact, it for sure is. TikTok is a platform where anyone and everyone has access to your content, no matter how narrow and closed off your own side of TikTok may feel. I have referred to this social component of TikTok as an “algorithmic closeness” [17] in between its users, where the algorithms continually show us similar content – and users – which is why it can feel like a more closed off space than it really is. When the Wall Street Journal [18] tested these algorithms in a recent study, using pre-designed bots that would pause on specific content, they found that bots that were programmed to pause longer on videos concerning sadness and depression suggested 93% of similar content on the bot’s For You-page. When we feel like we keep seeing the same types of content, that is by design. And when we feel intimately connected to each other because of this reoccurring content, that is also by design.

The author would like to thank the TikTok Research Lab and especially Jon Harman, Assistant Professor at Volda University College, Norway for directing my attention to the Black Dresses controversy.

Image Credits:

- Screenshot of #grief browser search on TikTok (editor’s screen grab)

- TikTok user @sunnybrooke14’s original video of sharing the good news about her new job in the ER (author’s screen grab)

- The band Black Dresses, photo from their profile on Bandcamp.com

- TikTok user @sunnybrooke14’s reaction video, commenting the dueted versions of her original video (author’s screen grab)

- The last frame of TikTok user @sunnybrooke14’s reaction video (author’s screen grab)

- Phillips, W. (2015). This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things: Mapping the Relationship between Online Trolling and Mainstream Culture. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2015, 7. [↩]

- Lu, Y., Pan, T., Liu, J., & Wu, J. (2021). Does Usage of Online Social Media Help Users With Depressed Symptoms Improve Their Mental Health? Empirical Evidence From an Online Depression Community. Frontiers in Public Health, 8. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpubh.2020.581088 [↩]

- Lagerkvist, A. (2017). Existential media: Toward a theorization of digital thrownness. New Media & Society, 19, 96-110. doi:10.1177/1461444816649921 [↩]

- Döveling, K., Harju, A. A. & Sommer, D. (2018). From Mediatized Emotion to Digital Affect Cultures: New Technologies and Global Flows of Emotion. Social Media + Society. January 2018. doi:10.1177/2056305117743141 [↩]

- Eriksson Krutrök, M. (2021). Algorithmic closeness in mourning: Vernaculars of the hashtag #grief on TikTok. Social Media + Society, 7(3): 1-12 [↩]

- Denisova, A. (2019: 29). Internet memes and society: Social, cultural, and political contexts. UK: Routledge [↩]

- Dawkins, R. (1976). The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [↩]

- Abidin, C. (2021: 80). Mapping Internet celebrity on TikTok: Exploring attention economies and visibility labour. Cultural Science Journal, 12(1), 77–103. https://doi.org/10.5334/csci.140 [↩]

- Clark, M. (2022). Nurse asks TikTok to stand in for her mother as she lands dream job. Yahoo! News. Published: February 15, 2022. https://currently.att.yahoo.com/att/nurse-enlists-internet-motherly-words-185840448.html. Accessed: March 2, 2022 [↩]

- Gibbs, M., Meese, J., Arnold, M., Nansen, B., Carter, M. (2015). #Funeral and Instagram: Death, social media, and platform vernacular. Information, Communication & Society, 18(3), 255–268. [↩]

- Neimeyer, R., Klass, D., Dennis, M. (2014). A social constructionist account of grief: Loss and the narration of meaning. Death Studies, 38, 485–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2014.913454 [↩]

- Abidin, C. (2019). Young people and digital grief etiquette. In: Papacharissi Z (ed.) A Networked Self and Birth, Life, Death, New York: Routledge, pp. 160-174. [↩]

- Gach, K. Z., Fiesler, C., Brubaker, J. R. (2017) “Control your emotions, potter”: An analysis of grief policing on facebook in response to celebrity death. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 1(CSCW), 1–47:18. https://doi.org/10.1145/3134682 [↩]

- Richards, M. (2022). TikTok is facilitating the spread of misinformation surrounding the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Media Matters. Published: February 25, 2022. https://www.mediamatters.org/russias-invasion-ukraine/tiktok-facilitating-spread-misinformation-surrounding-russian-invasion Accessed: March 2, 2022 [↩]

- CitatioStokel-Walker, C. (2022). TikTok Was Designed for War. Wired. Published: March 1, 2022. https://www.wired.co.uk/article/ukraine-russia-war-tiktok Accessed: March 2, 2022 [↩]

- Minsker, E. (2020) Black Dresses break up citing extended harassment from fans. Pitchfork. https://pitchfork.com/news/black-dresses-break-up-citing-extended-harassment-from-fans/ [↩]

- Eriksson Krutrök, M. (2021). Algorithmic closeness in mourning: Vernaculars of the hashtag #grief on TikTok. Social Media + Society, 7(3): 1-12. [↩]

- Wall Street Journal. (2021, July 21). Inside TikTok’s highly secretive algorithm. Wall Street Journal [Video]. https://www.wsj.com/video/series/inside-tiktoks-highly-secretive-algorithm/investigation-how-tiktok-algorithm-figures-out-your-deepest-desires/6C0C2040-FF25-4827-8528-2BD6612E3796 [↩]