Logged in to You: Negotiating Algorithmic Address in Streaming Women’s Television

Cara Dickason / Northwestern University

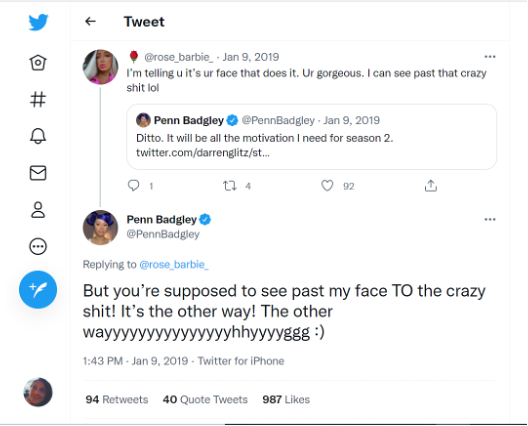

If you were a fan of the series You sharing your interest online in the winter of 2019, you might have received a 240-character lecture from its star, Penn Badgley. Badgley took to Twitter to respond to fans expressing their love for his character, Joe Goldberg, insisting that women’s apparent attraction to a murderous stalker reflected a larger problem. One user posted, “I’m telling u it’s ur face that does it. Ur gorgeous. I can see past that crazy shit lol.” For Badgley, what she “sees” misses the point: “But you’re supposed to see past my face TO the crazy shit! It’s the other way! The other wayyyyyyyyyyyyyyyhhyyyyggg :)” Although Badgley later described his tweets as “tongue-in-cheek,” his initial reaction implies that these women are watching You the wrong way. Their particular configuration of identification and desire constitutes a pathologized form of spectatorship, masochistic in its attachment to a “bad guy.” In pinpointing the problem of what viewers see past or to, Badgley acknowledges the multilayered nature of the show’s address, but prescribes a specific directionality to the viewer’s gaze.

His reaction seems to me a fundamental misreading of how women’s genres traditionally address their viewers. Women’s television genres in particular have been theorized to produce a more dispersed subject position; they address spectators able to hold multiple viewing positions at once.[1] And despite Badgley’s protestations, You is a romance. Showrunner Sera Gamble describes the series as inspired by classic romantic comedies, and insists, “the story only works if it’s also a real romantic comedy that you can root for.” By design, viewers might find themselves rooting for Joe to get the girl and reform his murderous ways (in whichever order). You invites and pokes fun at that stereotypical “I can fix him” energy. But by simultaneously exposing certain romantic comedy tropes as troubling and dangerous, the series guides the viewer to oscillate between multiple affective states—to see past Joe’s craziness to his attractiveness, and back again.

Given this concept, You may actually seem quite at home on its original network Lifetime, whose previous motto was “Television for Women” and which is now home to films like “A Date with Danger” and “Lethal Love Letter.” However, You only found popularity once it was released on Netflix. The streaming platform quickly committed to producing and streaming You’s second season, and the series was branded a “Netflix original.” Describing finding a new home for the series, co-producer Greg Berlanti jokes, “If Joe is a man who is simply just searching for love, well, then, our show finally found the right partner.” His playful comparison prompts a consideration of why, in fact, Netflix is the right partner for a former Lifetime series. And what does Joe’s particular search for love reveal about the new pairing? The complex narrative address of the series’ first season, I argue, sheds light on the ways that streaming platforms imagine and construct their spectators, offering a model of women’s spectatorship for the streaming era. Just as Joe stalks the object of his obsession and dangerously personalizes his courtship to his singular “you,” Netflix and other streaming services use algorithms that personally address you, the user, based on past and predicted behavior. You, however, foregrounds the dynamic difference between the imagined and constructed “you” and the actual person it hails. The show’s feminine spectatorial address produces an experience of negotiating multiple frames of reference at once, creating a revealing tension with the algorithmic address of Netflix.

The series’ second-person voiceover narration enacts many characteristics of algorithmic address. The specific “you” to whom Joe addresses his narration is Beck, a blonde twenty-something writer, whom Joe identifies as not like other girls. His initial attraction quickly turns to obsession, stalking, and murdering anyone who stands in his way, with his narration justifying every action as driven by love. Joe, of course, sees his surveillance as a form of care, enabling him to anticipate and fulfill her needs. And like any good targeting algorithm, Joe’s surveillance gets it right sometimes: he offers a trip to shop for furniture just when she’s in need of a new bed frame, like Instagram knows just when I need a new pair of sunglasses (you catch that, Instagram?). But the series also makes it clear that Joe’s assumptions are oversimplified and driven by his own desire. Beck and Joe first meet when she buys a book from his bookstore. When she uses her credit card to pay, Joe interprets what he wants to be true: “You want me to know your name.”

Joe’s pursuit of Beck engages some of the specific complexities of online surveillance. He steals her phone, and when he discovers that it’s still logged in to the cloud, he remarks, “that means I’m still logged in to you.” And tracking her location, communications, purchases, and searches certainly does provide a vivid profile. But You simultaneously emphasizes that the persona detectable through technology is only one facet of a person. Joe discovers this when first examining Beck’s social media presence. As the camera scans her photo feed, lingering here and there on an ice cream closeup or yoga pose, Joe narrates, “Your online life isn’t real. It’s a collage. You paste this Beck up, this together, cute, lovable, bendy, creature.” But Joe is not satisfied by the realization of multiple Becks, and becomes obsessed with knowing and coaxing out the “real,” most “authentic” Beck. Before murdering her ex-boyfriend, Joe accuses him, “You cast her in a role that isn’t her, and you trap her in it.” Of course, the series implies, that is exactly what Joe does, too. In The Burden of Choice, scholar Jonathan Cohn suggests that recommendation algorithms create a feeling of choice while actually limiting choices, working to make users more static and predictable.[2] Similarly, Joe is obsessed with aligning the version of Beck he has concocted as a fantasy with the real woman Beck by eradicating all the many versions of herself that exist.

The existence of multiple Becks, however, is directly related to the strategies Beck uses to negotiate the multiple frames of reference imposed on her by men with various forms of power. Those particular frames and her tactics of negotiation are shaped by her identity as a conventionally-attractive, young, white woman. The terms of her visibility would be markedly different if she faced interlocking oppressions, though the need to negotiate would very likely persist and heighten. In a scene in which Beck anxiously pleads with her MFA advisor to keep her funding, the traditional shot-reverse-shot sequence suddenly switches to wide-angle close-ups when the professor proposes that they go out for drinks, conveying a new, unsettling dynamic in the conversation. Her gentle mention of his wife and eventual cheerful assent demonstrate Beck actively calibrating her performance of the role he has cast her in in order to protect her career (by protecting his ego) while staying safe.

In the series finale, Beck must quite literally negotiate the box that Joe has put her in. After Beck discovers Joe’s many crimes, Joe traps her in a glass cage while he decides what to do. Her survival depends on convincing him that she authentically fits the fantasy he has created of her, that she can appreciate all of the things (i.e. stalking and murdering) he has done for her. Even providing him with an alternative version of events that exonerates him, she performs the version of “you” that Joe has been “seeing” all along. The series depicts these tactics of shifting between selves as a feminine practice of survival under patriarchy—even if they don’t always succeed.

You is not only attentive to these practices in its narrative, but constructs a spectatorial practice of negotiation and shifting in and out of subject positions through the formal address it enacts. In What Algorithms Want, Ed Finn argues that Netflix original series House of Cards embodies the algorithmic “ideal of personalization” through the lead character’s fourth-wall-breaking narration to the camera.[3] He suggests that, “Like Netflix itself, [the protagonist’s] core audience is you, the individual viewer with whom he makes regular eye contact.”[4] Joe, of course, also speaks to “you” in his narration, but significantly, Joe’s “you” is not addressing me—it’s addressing Beck. From the opening moments in which Joe’s voice speaks to “you,” I, the viewer, have to work to identify with his idea of Beck, if and when I want to. Joe’s “you” never quite fits me, just as it never quite fits Beck. You simultaneously embraces and undermines the nature of algorithmic address by mobilizing a feminine spectatorial practice of negotiation. I shift in and out of those “you” positions—both Joe’s and Netflix’s—and my identifications, desires, and resistance are not limited to any one direction or contained by any singular profile. By incorporating that dynamic, contemporary women’s television grapples with the new forms of power deployed by streaming technology that blurs the distinction between watching and being watched.

Image Credits:

- Formerly a Lifetime series, You is now branded a “Netflix Original.”

- Actor Penn Badgley responds to fans on Twitter who “romanticize” his character Joe Goldberg, a serial murderer (author’s screen grab).

- In season one of You, Joe (Penn Badgley) stalks the social media of his obsession, Beck.

- Beck (Elizabeth Lail) bargains with Joe to free her from his cage.

- See Tania Modleski, Loving with a Vengeance: Mass Produced Fantasies for Women (Routledge, 2007); Brenda Weber, Makeover TV: Selfhood, Citizenship, and Celebrity (Durham: Duke UP, 2009); Mimi White, Tele-advising: Therapeutic Discourse in American Television (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1992); among others. [↩]

- Jonathan Cohn, The Burden of Choice: Recommendations, Subversion, and Algorithmic Culture (New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 2019). [↩]

- Ed Finn, What Algorithms Want: Imagination in the Age of Computing (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2017), 107. [↩]

- Finn, 106. [↩]