The Costs of Hope in The Chair and The Bold Type

Kelly Coyne / Northwestern University

Early in The Chair, a Netflix miniseries from Fall 2021, the washed-up writing professor Bill Dobson (played by a craggy Jay Duplass) announces himself in the new office of Ji-Yoon Kim (Sandra Oh), a Korean-American professor who has just been named chair of the English department at Pembroke University. Even though Ji-Yoon is now his boss, Bill pleads to get together with her. First, though, he frames her new position as a golden ticket, a place of both security and satisfaction. “You don’t have anything to prove to anyone anymore. Look at you—you did it. You ascended the ranks of your profession.” To broadcast the prestige of her title, the show lingers on the chair’s office: wainscoted walls, a gold nameplate on the door, leather chairs, banquet lamps, portraits of mustached men. Accompanied by dramatic opera, it’s a little much, like a fantasy of academic life from someone who hasn’t been there. But the two are captured in handheld. It hints at an unsettledness—an ambivalence—lying beneath the surface. What happens if you get what you work for, but then you realize that the prize isn’t what you actually want?

The “quits” rate—for those who work everywhere from warehouses to offices to restaurants—hit record highs in 2021. With it has come a wave of media exploring the benefits of quitting. “I’m so tired that I might / quit my job, start a new life,” sings Olivia Rodrigo in “brutal.” “The power of no: Simone Biles, Naomi Osaka and Black women’s resistance,” reads a headline about the athletes’ decisions to opt-out, after spending years (lives, really) training for world-class sporting events. On TikTok, “#QuitMyJob” went viral. “Quitting your job is hot this summer,” proclaims a recent article in The Atlantic, titled “What Quitters Understand About the Job Market.” The events of 2020—a year marked by COVID and the racial reckoning spurred by the murder of George Floyd—began to erode confidence, in the mainstream, in the tenets of the American Dream. Now, at the end of 2021, there is widespread suspicion of the once-untouchable mantra to never give up.

For Lauren Berlant, who died this summer, cruel optimism is when fantasies of the good life undercut your ability to obtain it. Cruel optimism demands sacrifice in exchange for the hope that, one day, you will get what you deserve. It can be used to manipulate laborers, to extract as much as possible from them. A CEO promotes cruel optimism when suggesting to their underlings that if they work hard enough, they might be able to have their position one day; a manager does when telling an unpaid intern that they might ultimately get a job if they stay long enough. Of course, none of these are promises: there is no specified period of time, there is no contract. “Why,” Berlant asks, “do people stay attached to conventional good-life fantasies—say, of enduring reciprocity in couples, families, political systems, institutions, markets, and at work—when the evidence of instability, fragility, and dear cost abounds” (Berlant 2)?

For The Chair, the solution to cruel optimism is realizing that the C-suite is not all it’s cracked up to be, but only once you’ve earned admission there. This show is not the only one from 2021 that depicts a character taking a prestigious job she spent years optimistically striving for, only to encounter uncertainty once experiencing the life that comes with it. In The Bold Type—the Freeform show that premiered in 2017, with a finale this past summer—Jane Sloan (Katie Stevens), a white writer-turned-editor, is groomed for years to become the next editor-in-chief of Scarlet magazine, her dream job. After accepting the offer, Jane realizes that managing budgets and conducting advertising meetings is not nearly as fulfilling to her as being a writer. The Bold Type’s ending chronicles Jane stepping down to become a freelance writer in Paris. (Jane has already spent time as a freelance writer, and this was not something she enjoyed.) Echoing The Bold Type’s beatific final note, the penultimate scene of The Chair shows Ji-Yoon—self-actualized, lit up by the sun streaming through her classroom windows, ambient music in the background—teaching, after being forced from her post. She reads the Emily Dickinson poem, “‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers,” and asks her students: “what do you think she means ‘hope never asks a crumb’ of her?” With the dreamy music and lighting, there is an irony to the question. Presumably, the class will ponder the costs of hope.

Such endings cut through the long-held fantasy that advancement—and its trappings of power and money and perks—leads to satisfaction. Both protagonists crucially begin these series in plum jobs that barely exist anymore: a salaried writer at a women’s magazine, and a tenured professor. (We are meant to assume they have health insurance, a benefit seldom offered these days to magazine writers and academics.) But still, they strive, driven by the fantasy of being in charge that is dangled in front of them. That these characters already have dream jobs and they still want more indicates how easily a basic sense of hope can be instilled and exploited by the workplace. In putting the viewer in the shoes of a character who gets all of the power they wanted, before realizing that they already had the good life, these shows frame the opt-out as an admirable, self-actualizing move, even if the positions they retreat back to are nostalgic American myths.

Long before it had connotations of relieving oneself from commitments, the term quit meant “to pay a person his or her due”; sometime later, it evolved to mean “to set free” (“Quit, v”). Part of what keeps Jane and Ji-Yoon tied to their positions is guilt at giving up a sought-after job where those like them are underrepresented. There is a sense that in taking these posts, they are doing something good for their gender, for the future, and, most definitely, for the future of their gender. Pembroke’s name likely references Brown’s gender studies center, a wink at the social-justice culture that drives much of the show’s tension, embodied by Ji-Yoon’s wide-eyed students, both earnest and seemingly unaware of the extraordinary advantages baked into attending the fictionalized but Ivy-League Pembroke. From her new vantage, Ji-Yoon begins to experience these ideals in a different way. There is not only her guilt at the realization that, as a woman of color, this isn’t actually what she wants, but there is also her cognitive dissonance when the school newspaper broadcasts that she issued a gag order to one of her advisees when she suggested that she not speak to the press about a scandal involving Bill.

When Ji-Yoon ultimately receives a vote of no confidence from the rest of the English department—an event that is framed as a relief for her—she passes off the job to the only other tenured woman professor in the department, a white woman whose senility is mocked relentlessly by the show. It’s a joke: Ji-Yoon’s competence contrasted against someone who becomes a stand in for everything wrong with academia, with her out-of-touchness, her second-wave feminism, her abused tenure. Ji-Yoon, at the end, teaches in a department that is undeniably a sinking ship. In The Bold Type, the editor-in-chief job goes to Kat (Aisha Dee), a Black woman. Jacqueline, the outgoing editor-in-chief, is played by Melora Hardin (best known as Jan in The Office), and she clasps her hands around Kat’s when she gives the offer, staring deep into her eyes—Jacqueline’s characteristic moves. “I was trying to replace myself with someone like me, but someone like me is not the future of Scarlet,” she says. Kat responds: “Sorry—I’m trying to catch up, because it wasn’t that long ago that—I mean, we were sitting right there and you fired me.” But she is so thrilled by the offer that she cries, exclaiming that she won’t need any time to think about whether she wants to accept.

By handing it off to another woman, Jane and Ji-Yoon are set free from not only the job, but also the attendant guilt. So is the viewer who sits with them. And through Ji-Yoon and Kat, these women of color, both The Chair and The Bold Type conclude by renewing a fantasy of human fulfillment within workplaces that instill the sense in their workers that they are special, that they are the answer, in order to draw them in and keep them coming back for more, no matter what has happened in the past. It lands differently now—I’m not as optimistic this time around.

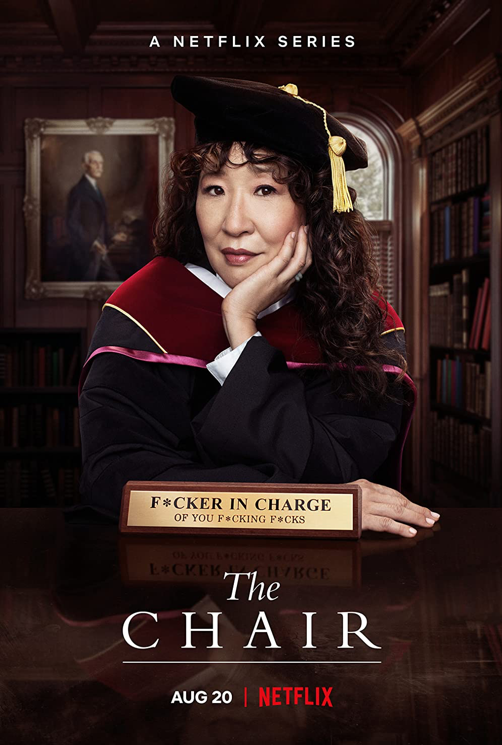

Image Credits:

- Ji-Yoon Kim (Sandra Oh) admires her new office in The Chair (author’s screen grab)

- Olivia Rodrigo announces the music video for “brutal”

- Sandra Oh in a promotional graphic for The Chair (Netflix)

- Aisha Dee in a promotional graphic for The Bold Type

Berlant, Lauren. Cruel Optimism. Duke University Press, 2011.

Gatwiri, Kathomi and Lynne McPherson. “The Power of No: Simone Biles, Naomi Osaka and Black Women’s Resistance.” The Conversation, 29 July 2021, https://theconversation.com/the-power-of-no-simone-biles-naomi-osaka-and-black-womens-resistance-165318.

“Job Openings and Labor Turnover Summary.” US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 12 October 2021, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/jolts.nr0.htm.

“Quit, v.” OED Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/156786.

Peet, Amanda, creator. The Chair. BLB and Nice Work Ravelli, 2021. Netflix.

Rodrigo, Olivia. “brutal.” YouTube, uploaded by Olivia Rodrigo. 23 August 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OGUy2UmRxJ0.

Thompson, Derek. “What Quitters Understand About the Job Market.” The Atlantic, 21 June 2021, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/06/quitting-your-job-economic-optimism/619242/.

Torres, Monica. “People Are Sharing The Moment They Quit Their Toxic Jobs On TikTok, And It’s A Journey.” The Huffington Post, 15 July 2021, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/tiktok-quit-their-job-videos_l_60ed9ecae4b01ba8eecfa869.

Watson, Sarah, creator. The Bold Type. Freeform and Universal Television, 2017-2021. Hulu.

Pretty! This was a truly noteworthy post. Thankful to you for giving these subtleties.