Everytown, USA, Everyshow, USA: Riverdale as Intentionally Intertextual

Caroline N. Bayne / UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA, TWIN CITIES

The CW’s Riverdale premiered in early 2017 and has since become a beloved, reviled, and chaotic example of contemporary teen television. The program is a contemporary rendering of the Archie comics and broader Archive universe featuring murder, cults, and aliens alongside milkshakes, muscle cars, and high school football. In a 2016 interview at San Diego Comic Con, executive producer and the show’s creator Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa discusses the duality of Riverdale as both a well-known example of American nostalgia media and a darker teenage drama (see video below). An interviewer asked about the comparisons made by critics between Riverdale and cult television show Twin Peaks ahead of the release of the series and Aguirre-Sacasa replied, “It is a hard tone to wrap your head around because you think Twin Peaks? That’s all murder and darkness. And I think when people hear that, their fear is ‘Why do that to the Archie characters? If you want to do a teen Twin Peaks, why not create your own characters?’ For me, I really think the show lives in the tension between the innocent, the wholesome, the 1950s nostalgia of Archie and the contemporary darker world.”

Aguirre-Sacasa’s point about the show thriving in the tension between the wholesome and the dark, indebted both to the source material of the original Archie comics, first published in 1941 and popularized during the late 1950s, and the current narrative and aesthetic landscape of teen television, which places as much an emphasis on the foibles of high school as the mysteries, murders, and even supernatural happenings in small towns, produces an explicitly intertextual and self-reflexive program. Here, I utilize Jonathan Gray’s (2006, 4) definition of intertextual intent: “texts that aim themselves at other texts and genres, and that want us to read them through other texts or genres.” While Gray is focused on the role of parody in critical intertextuality and I don’t read Riverdale as parody, I do find that its incredibly dense field of reference to the “golden age,” during which the original comics were popularized, and its complication of an enduring example of all-American media do create a critically intertextual program. And while Riverdale may not be parody and could easily be misread as shallow or self-servingly edgy, we might consider its utilization of a 1950s text, universe and overall ideology and the subsequent darkening and disrupting of those characteristics as a pointed critique of the fantasy of all-American media premised upon small towns, high school romances, and teenage frivolity and fun.

The ideologies of both 1950s media and teen media function within Riverdale and often compete with each other across episodes and storylines. Domestic sitcoms from the 1950s and 60s that feature the mundane everyday issues faced by teen characters, such as Betty Anderson from Father Knows Best (CBS 1954-55; 1958-1960; NBC 1955-1958) developing a crush on a boy at school much to the dissatisfaction of her father, resurface in Riverdale to some extent. The “epic highs and lows of high school football” and cheerleader tryouts, along with the incestuous relationship between the main characters, where everyone kisses everyone else, couch the series in the recognizable innocence and in some ways, mundanity of early domestic sitcoms as well as more recent examples of teen-focused television where the bubble of high school seems impenetrable and all-encompassing.

Much like many other contemporary retellings, reimaginings, or reboots of teen television premised on well-established television, comics, or film, Riverdale is beholden to the expectations and familiarity established by those earlier texts and must, to some degree, demonstrate a self-reflexivity to that fact. I see this most reflected in the program’s mise-en-scène and its obsession with legacy media and technologies, as well as its utilization and upsetting of popular teen media character types such as the girl next door, the mean girl cheerleader, and the star quarterback. Additionally, Riverdale not only speaks back to its mother text but also to the teen films and television programs of the 1990s and early aughts, which I discuss in more detail below.

The temporal space of Riverdale is muddled to the point where, scene by scene, the periodization and corresponding aesthetics appear to change. The characters have iPhones and landlines and use Macbooks and typewriters interchangeably. In some ways, the appearance of contemporary technologies such as cellphones and laptops, as well as the brazen use of product placement, is the only signal that Riverdale is a program set in current day. Importantly, too, Riverdale is not an isolated example of this type of unspecified setting or aesthetic in teen television. Other examples include (and I’m sure there are many more) Netflix’s The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina (2018-2020) (also created by Aquirre-Sacasa and part of the Archie universe) and A&E’s Bates Motel (2013-2017). These examples are also reimaginings of past film, television, and comics.

A close reading of the mise-en-scène of particular episodes reveal the way Riverdale as a text “[comments] upon the mechanics of other media texts and institutions” and that, perhaps demonstrates the increasing obsolescence of golden age media texts (Gray 2006, 5). Further, as Riverdale, through its intertextual approach reveals, genres are not fixed and outlasting, but instead “are only as good as they are culturally useful to specific groups at specific times” (Mittell 2004, 17). As such, the Archie universe’s update to reflect the reality of the contemporary teen media landscape coincides with its perversion of the wholesome 1950s Archie universe and how that version no longer serves a culturally useful purpose.

Much has been written on television’s preoccupation with its own past and the consequence of its earliest programming producing a particular type of wholesale representation of American living in the midcentury (Coontz 1992; Leibamn 1995; Spigel 2001; Hastie 2007; Stabile 2018). Broadly, Riverdale utilizes a range of nostalgic iconography throughout its episodes that recall the aesthetics of the 1950s as held in popular memory such as soda shops, letterman jackets, and muscle cars. Additionally, throughout the series but particularly in seasons 4 and 5, the program demonstrates a compulsion to focus its storylines around legacy media such as VCRs, VHS tapes, and vintage television sets. In season 4, episode 4, “Halloween,” the families of Riverdale find videotapes on their doorsteps – from here, the frequency of VHS and VCRs used on-screen by the characters steadily increases, as do the families gathering around their sets to watch the contents of the tapes. The televisions in the homes of Riverdale’s characters are not sleek, mounted flatscreens (save for that of the Lodge family, wealthy and metropolitan) but bulky sets or small, dated boobtubes.

The storyline of the video tapes features a season-long villain named The Auteur who records and leaves ominous videos for the families of Riverdale, often featuring people wearing large, exaggerated masks of the original Archie characters committing violent crimes. Here, the use of legacy media in the form of vintage televisions and VHS tapes function simultaneously to reflect the town’s charming resistance to modernity, which adds to how it is described by character Jughead Jones in the pilot episode via a voiceover: “From a distance [Riverdale] presents itself like so many other small towns all over the world … safe, decent, innocent,” as well as the perversion of domestic technologies and the original Archie characters themselves. Jughead continues, “Get closer, though, and you start seeing the shadows underneath.” This, perhaps, is one of the best examples of Aguirre-Sacasa’s assertation that Riverdale shines in the tension between the narrative and aesthetic modes of wholesome familiarity and contemporary darkness.

Riverdale is not only intertextual in its aesthetics but also in its casting choices. The casting of uber famous teen stars from the 1980s, 90s, and early aughts is another major strategy of intertextual intentionality utilized by the program, this time on the terrain of teen television and film. Luke Perry (90210, Buffy the Vampire Slayer), Molly Ringwald (Pretty in Pink, The Breakfast Club), Skeet Ulrich (Scream, The Craft), and Mädchen Amick (Twin Peaks, Gilmore Girls) play the parents of several of the main characters including Archie, Betty, and Jughead. Additionally, Riverdale, in all of its high school milestone episodes, such as season 5, episode 1, “Climax,” in which the seniors of Riverdale High attend their final school dance, utilize nostalgic details that speak back to the titan era of teen media of the 90s and early aughts.

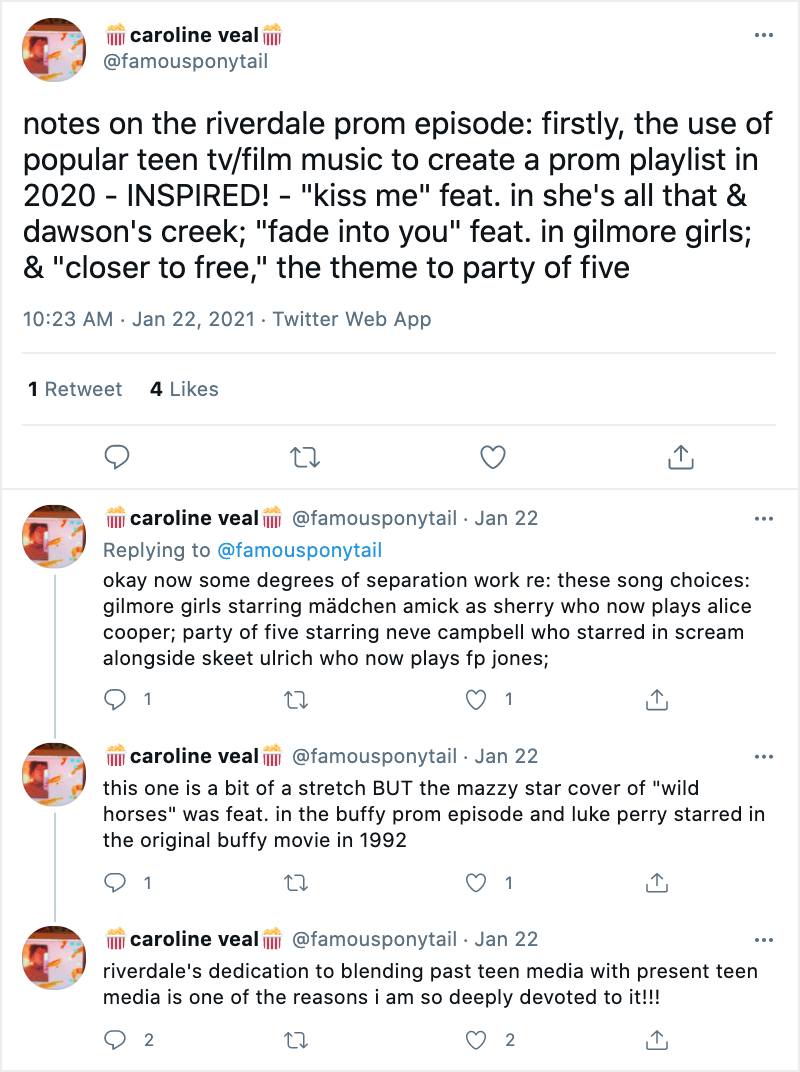

After watching the prom episode, I mapped out the details of the dance scenes into a web of references from earlier teen media. On January 22, 2021, I composed a series of tweets titled “Notes on the Riverdale prom episode,” posted below. While some of my speculations are likely just that, I also believe we would be remiss to assume Riverdale’s curation of prior aesthetics was not intentionally intertextual and working to establish itself in direct conversation with these older texts.

Image Credits:

- The set of Pop’s Chock’lit Shoppe in Riverdale (2017–present).

- Executive Producer Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa from Riverdale’s Roundtable Interviews at SDCC 2016 (The Nerd Element, 2016).

- Riverdale, Season 4, episode 4 “Halloween.” (author’s screengrab)

- Riverdale, Season 4, episode 4 “Halloween.” (author’s screengrab)

- Riverdale, Season 4, episode 4 “Halloween.” (author’s screengrab)

- Riverdale, Season 4, episode 19 “Killing Mr. Honey.” (author’s screengrab)

- Caroline N. Bayne’s tweets on the Riverdale prom episode.

Coontz, Stephanie. 1992. The Way We Never Were: American Families and the Nostalgia Trap. New York: Basic Books.

Gray, Jonathan. 2006. Watching the Simpsons: Television, Parody, and Intertextuality. New York: Routledge.

Hastie, Amelie. 2007. Cupboards of Curiosity: Women, Recollection, and Film History. Durham: Duke University Press.

Leibman, Nina. 1995. Living Room Lectures: The Fifties Family in Film and Television. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Mittell, Jason. 2004. Genre and Television: From Cop Shows to Cartoons in American Culture. New York: Routledge.

Spigel, Lynn. Welcome to the Dreamhouse: Popular Media and Postwar Suburbs. Durham: Duke University Press.

Stabile, Carol. 2018. The Broadcast 41: Women and the Anti-Communist Blacklist. Cambridge: MIT Press.