Experiential Advertising: The World of Coca-Cola

Cynthia B. Meyers / College of Mount Saint Vincent

The World of Coca-Cola, located in Atlanta, Georgia, is a museum/indoor theme park that includes a gift shop and a tasting room, and is a prime example of effective experiential advertising. In exchange for their ticket purchase and their attention, visitors are educated in all things Coca-Cola: its history, icons, philosophy, and products. In March 2016, I joined other visitors, paying $16 for the privilege of standing in a series of lines: first to watch an introductory film showing happy people of all kinds consuming Coke everywhere; then to have a photo taken with an actor costumed as the advertising icon polar bear; then to enter “The Vault,” where the secret formula is supposed to be safely stored, away from competitors; and finally to taste Coca-Cola products from all over the world. Following the paths and the lines, visitors are ultimately funneled through a store where they can buy more Coca-Cola advertising to take home with them: toys, games, clothing, dishes, and mementoes.

“Advertising” usually differs from “content” in that content is what the audience wants to see, while advertising is what the advertiser wants the audience to see, so much so that advertisers pay media companies to expose audiences to it. Magazine ads appear next to magazine articles, television commercials interrupt narrative programs, and it is easy to tell which is content and which advertising. The media companies finance and create the content to attract audience segments advertisers target; the advertisers (“brands”) and their agencies create the interstitial advertising and pay for its placement. This distinction between is harder to parse in the World of Coca-Cola. Most people claim they strive to avoid advertising, but visitors to the World of Coca-Cola pay money for it. Perhaps not many brands can get away with this. In light of the decline of linear television, however, which developed as the single most powerful brand-image building medium ever by forcibly exposing mass audiences to interstitial commercials, such experiential advertising strategies may be a sign of things to come.

The visit begins in the “Coca-Cola Theater” with a viewing of a “celebration of life’s Moments of Happiness,” actually an extended large-screen commercial featuring much togetherness, bonding, and joy. Coke’s advertising, like that of its competitors, uses such themes not only to create positive associations with its brands, but also to inculcate in its consumers a sense of virtuousness. We’re not drinking a sugary liquid-—we’re bonding with our loved ones and affirming our shared humanity! To emphasize Coca-Cola’s cross-cultural appeal, much of the film features performers from all over the world bound together by their common love of Coke. The audience is encouraged to imagine that they are not just sitting in a theater seat in Atlanta but traveling on a “Journey around the world in a thrilling 4-D movie experience.” This sets the emotional temperature for the rest of the visit: joyful, colorful, and loving.

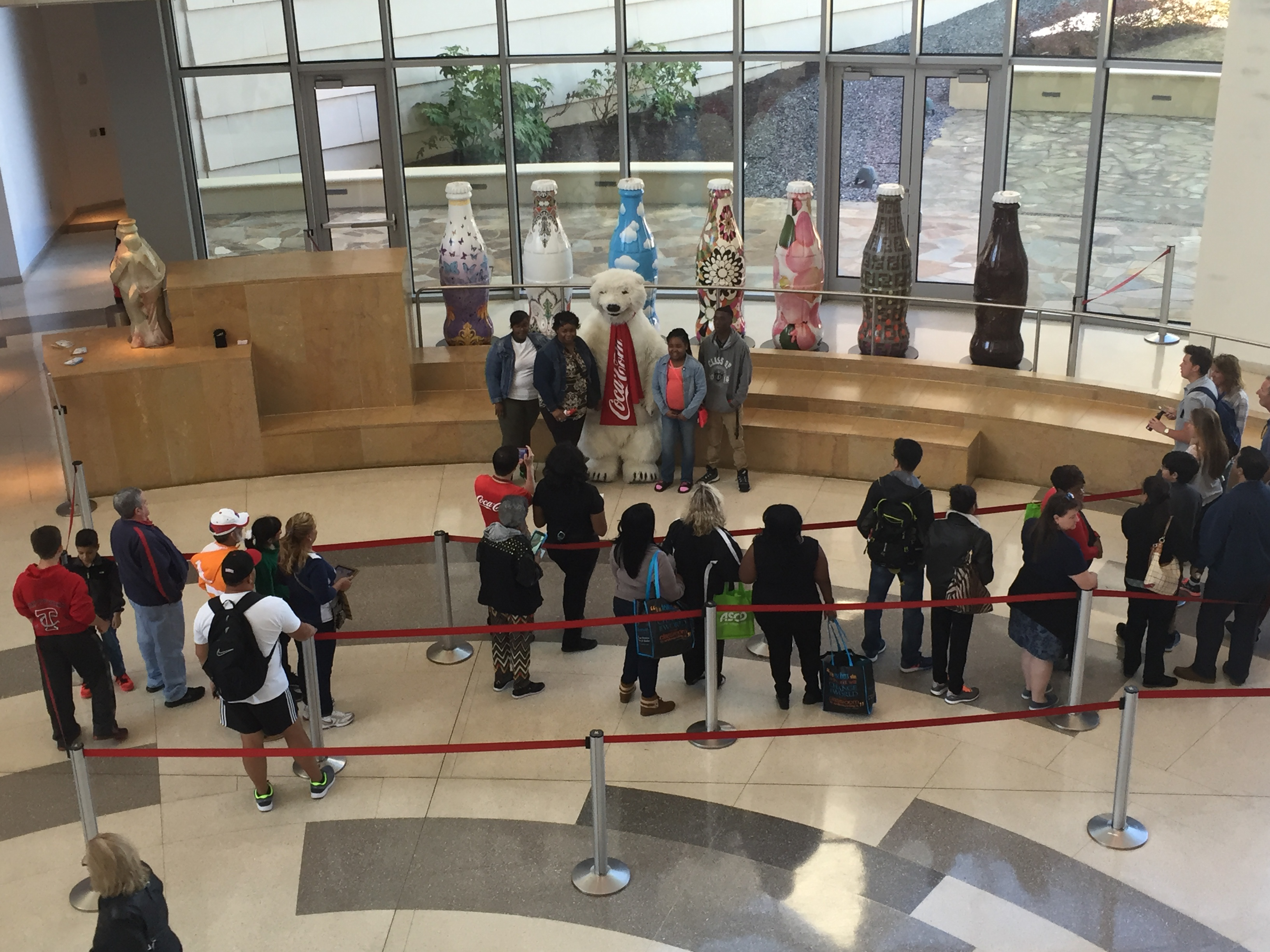

Next, most visitors wait in line to “meet our most beloved character”: somebody in a polar bear costume. The white fur fits well with Coke’s red and white iconography; the cuddly furry advertising icon poses with arms around visitors, suggesting a combination of emotional warmth with refreshing soft-drink coolness. Back in the 1920s, another soft drink brand, Clicquot Club ginger ale, likewise employed iconography of the arctic to associate its product with cool refreshment; its radio show featured a band called the Clicquot Club Eskimos and included the sound of sled dogs barking in musical time. The Coke polar bears, as seen in the commercials featured in a small screening room called the “Perfect Pauses Theater,” are depicted as cuddly couch potatoes watching the colorful northern lights while sipping soda—just like us.

“Immerse yourself in the rich heritage of Coca-Cola,” suggests the promotional video. Coca-Cola is not merely a sugary drink but an icon of our shared cultural past. “Rich heritage” are buzzwords implying “wealth,” something most of us would like to have more of. “Heritage” sounds less boring and dry than “history” while avoiding the risks of actual historical inquiry, which could expose who knows what examples of dishonesty and exploitation.

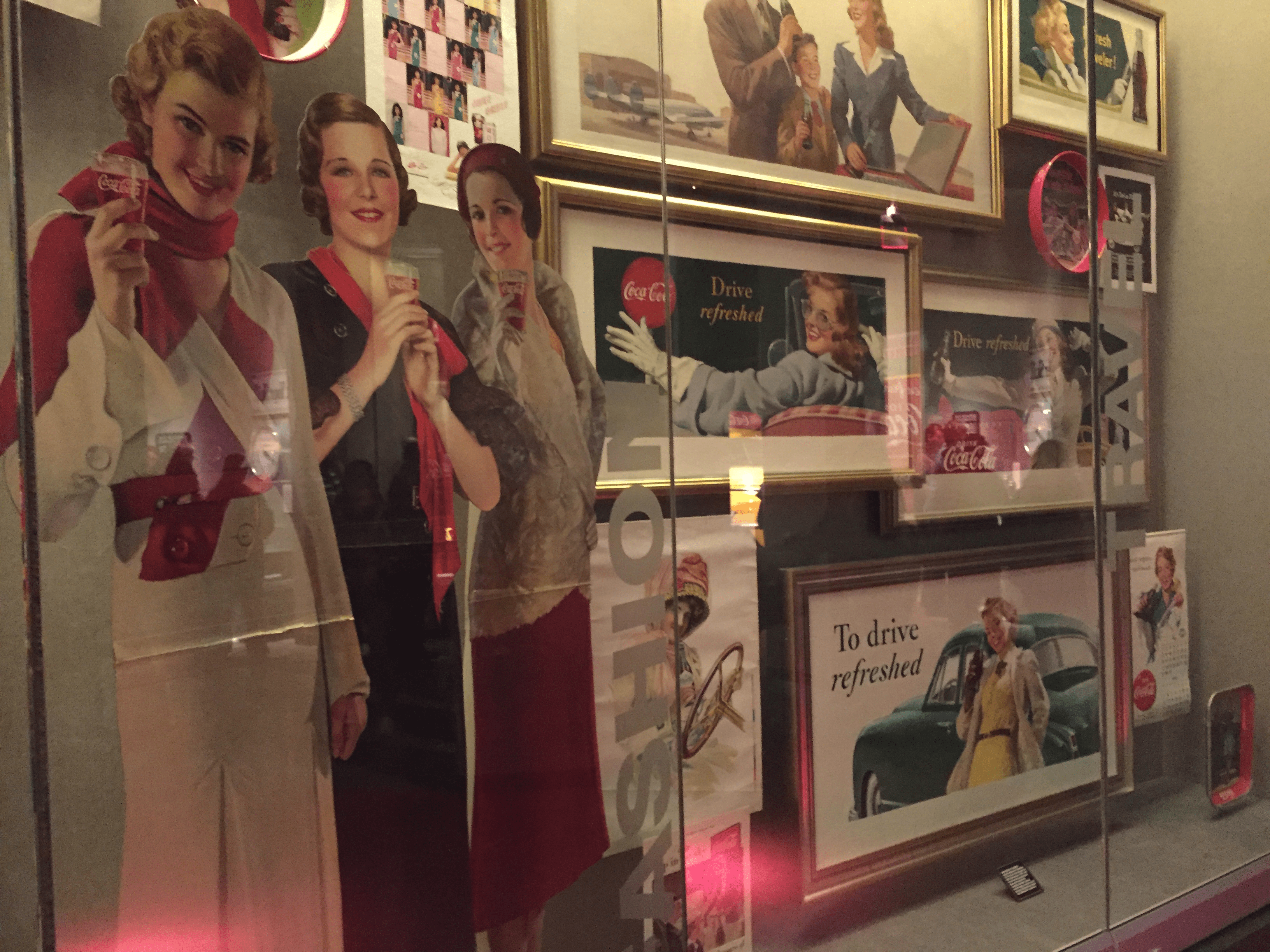

In its exhibit of its past advertising, visitors are encouraged to “Take a walk through the fascinating story of Coca-Cola.” Glass cases filled with old ads and memorabilia document Coca-Cola’s advertising strategies: Americana, friendship, family, and celebrity.

Purged of any potentially offensive images, these representations of the past seem ideally suited to illustrate Michael Schudson’s notion that American advertising is a form of “capitalist realism.” Unlike the placards at actual museums, the wall signs here simply replicate much of the advertising copy: “No matter what the era, Coca-Cola imagery captures the lifestyles of the day while reminding us that Coke is a natural companion to good times.”

In a room featuring images of many of the celebrities, performers, and music artists Coca-Cola has sponsored and hired to promote Coke, the wall placard reminds us that the “display of these materials in this museum is for historical and educational purposes only and is not intended to imply endorsement by any person or organization of The Coca-Cola Company or its brands today.”

To learn more about the history of the company, however, visitors must stand in another line, which leads at last to the “Vault of the Secret Formula,” marked off with a forbidding “Access Restricted” sign. Making the room more exclusive and requiring patrons to wait in line are ways to stimulate interest—like any nightclub, it looks more desirable if other people are standing in line to get in. Interspersed with a variety of interactive devices and games are placards describing the development of the soda industry.

Claiming Coke’s “magic formula” became the “most sought after—and closely guarded—trade secret in American history,” the exhibit heightens the drama by including security theater tactics, such as a bank of putative security video monitors and security guards standing in front of giant steel bank safe doors. Visitors may stand in line and pay for the privilege of having their photograph taken in front of this impressive steel vault.

It wouldn’t be a modern museum experience without interactivity: in an area labeled “Pop Art,” visitors may use interactive devices to create their own imagery and to write “My Coke Story.” As a placard explains, “Each moment of every day, someone in the world makes a special connection with Coca-Cola.” To encourage visitors to handwrite or type out a personal story about consuming Coke, they are told, “If chosen, your story might end up on display here at the World of Coca-Cola or on our website.” Free user-generated advertising for Coca-Cola is redefined as an exciting opportunity for the consumer. We can see some of the winners of this contest, such as a visitor named Romero, who wrote, “I like to share a Coke with my family at the beach in Puerto Rico.” This bears the same relation to public history initiatives, such as local oral history projects, as does the World of Coca-Cola to a traditional museum.

The penultimate experience is a room filled with machines dispensing Coca-Cola products from around the world. After immersion in movies, ads, and memorabilia, visitors are probably thirsty, or, at the least, in need of a sugar boost. Emphasizing Coca-Cola’s global reach and cross-cultural significance, signs invite visitors to “Sample 100+ flavors from around the world.” Various beverages are labeled by the country where they are marketed (the Beverly, for example, is sold in Italy). And visitors are encouraged to provide yet more free advertising for Coca-Cola. A placard instructs: “Taste it, snap it, post it” on social media.

The final experience is of course the store where you can “take the excitement of your visit home with you.” It’s not possible to get out without passing through the store. To ensure excitement, there are turnstiles to enter and long lines at the cash registers. Visitors who buy the toy polar bears, basketballs, footballs, mugs, dishes, t-shirts, sweatpants, pajamas, or other memorabilia ensure that Coke’s logo, message, and brand image are distributed more widely—and at the consumer’s cost, not Coca-Cola’s.

Coca-Cola is one of the rare long-lived brands that have succeeded in creating an iconography that is nearly synonymous with American culture. Far more effective than a standard television commercial, the World of Coca-Cola’s immersive and experiential advertising fully exploits the brand’s role in American popular culture and consumers’ emotional lives. By the time its visitors leave, they will presumably be sated by soda, cheered by polar bears, and feel well bonded with family members and the whole human race. And they didn’t have to sit through a single interruption of their favorite television program.

Image Credits:

- “Coca-Cola Theater” audience. (author’s screen grab)

- Line to take a photo with the Coke polar bear. (author’s personal collection)

- Old ads with slogans including “Entertain your thirst”. (author’s personal collection)

- Ads with the slogan “Drive refreshed”. (author’s personal collection)

- Coca-Cola promotional material by The Supremes. (author’s personal collection)

- Line to the “Vault of the Secret Formula”. (author’s personal collection)

- Guard stands in front of a vault door. (author’s personal collection)

- A girl at an interactive exhibit. (author’s personal collection)

- A boy at a soda fountain sampling a flavor. (author’s personal collection)

- The store is the final World of Coca-Cola experience. (author’s personal collection)

very interesting!

Claiming Coke’s “magic formula” became the “most sought after—and closely guarded—trade secret in American history,” the exhibit heightens the drama by including security theater tactics, such as a bank of putative security video monitors and security guards standing in front of giant steel bank safe doors. Visitors may stand in line and pay for the privilege of having their photograph taken in front of this impressive steel vault.