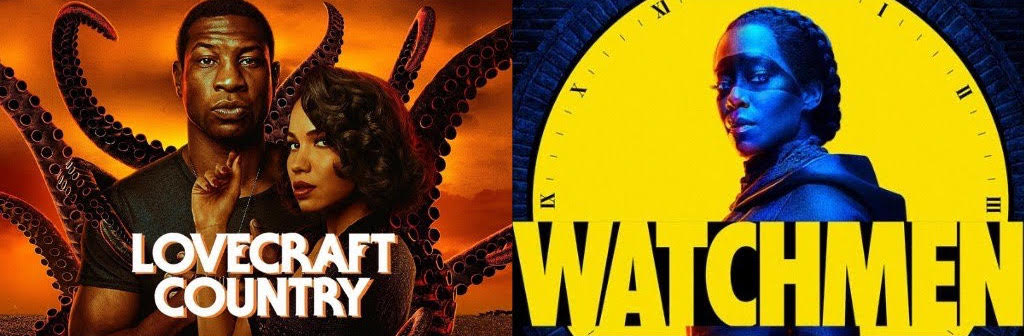

Over*Flow: Watchmen Walked So That Lovecraft Country Could Run: The Jordan Peele Effect on TV’s New Black Sci-fi

Tia Alphonse / University of Missouri

For most African Americans, there are few moments in American history to which they would willingly return. Recent television series are trying to create spaces where Black people are able to confront historical legacies on their own terms. The worlds of Watchmen (2019) and Lovecraft Country (2020) are genre-bending narratives that subvert the go-to Hollywood choices of using historical or epic dramas to deal with the issue of race. Instead, these new series are using more unorthodox genres like sci-fi to assist Black people as they enter and exit their own racial traumas.

HBO’s comic-adapted series Watchmen swept the 2020 Emmys on September 20, amassing 11 awards in the limited-series categories. Although critics love the show, Watchmen’s reviews on Rotten Tomatoes are polarizing with a 96-percent rating from critics and a 55-percent audience rating. [1] In Metacritic’s user reviews, fans of Alan Moore’s original “Watchmen” comic said the television series veers too far from the source material by focusing on political issues. [2] The “Watchmen” comics explored an America where the United States wins the Vietnam war and the Watergate scandal is never exposed. In Moore’s comics, the presence of superheroes and vigilantes changes the course of history in the 1940s and 1960s. [3] Series creator Damon Lindelof felt he could use the original source material as canon to build a storyline more relatable than retelling a Cold War-centered story about American nationalism. Lindelof asked himself: “What, in 2019, is the equivalent of the nuclear standoff between the Russians and the United States?” He said, “It just felt like it was undeniably race and policing in America.” [4]

Watchmen’s pilot episode opens with a reimagined scene from the 1921 Tulsa Massacre. The events unfold primarily through the eyes of a young boy as planes rain down bullets and bombs. White men are executing Black men and women on the streets. Coaxed into a wooden crate by his parents, the boy is rushed out of town as bullet holes pierce his box. He peeks through an opening and sees horses dragging lassoed bodies down the street. [5] With this opening scene, director Nicole Kassell permanently imprints the episode’s images into viewers’ minds and sparks a conversation about Tulsa’s Black Wall Street that had all but been forgotten by white Americans and never taught to others.

“It just reminds you how much pain our country was built on that we haven’t talked about.” – @ReginaKing

— Watchmen (@watchmen) June 20, 2020

The #Watchmen team shares how they recreated the massacre of Black Wall Street in Tulsa, 1921. pic.twitter.com/BKwf00HO16

For both Black and white audiences, this series speaks to each group in distinct ways. Watchmen allows audiences to enter fictional worlds, although based on real historical events, and explore racial trauma outside its traditional depictions in slavery-centered storylines. By using unconventional genre storytelling, writers and directors allow audiences to return to these spaces to find restoration and redemption. The science fiction/fantasy and horror genres create spaces for characters to have more agency and offers Black protagonists the tools to fight white oppression. For so long, the only portrayals taken seriously by critics were rigid stories about the Black experience rooted in racial oppression. Whether it be historical portrayals of Black icons like Martin Luther King, Jr. in Selma (Ava Duvernay, 2014) or historical dramas about slavery in 12 Years A Slave (Steve McQueen, 2013), audiences often trust these stories to retell events as they happened. In their familiarity and repetition, these drama films no longer challenge audiences to look introspectively at the way racism is perpetuated in the present. [6] Watchmen so poignantly balances acknowledgement of the real-lived experiences and trauma of historical racism, yet in fantasy, it also creates new characters undefined by the timeline and constraints of the past. This conscious decision allows creatives to produce Black protagonists that can fight back in unconventional ways.

Watchmen and Lovecraft Country: Easter eggs for Black fans

1 of my fave parts of tonight’s watchmen episode were the 2 newspaper clippings about the SOLD OUT nazi rally at madison square garden (1938 i think) and about them marching on parade in Long Beach, no more than 10 miles from me right now. REAL EVENTS.

— Glare Huxtable (@radseed) November 25, 2019

In the sixth episode of Watchmen titled “This Extraordinary Being,” audiences are taken along Will Reeves’ journey to becoming a vigilante. Will is the older version of the boy we meet in the first episode. He grows up to become a police officer in New York City before realizing the problems he escaped in Tulsa still exist and have infested his police unit. Audiences watch as Will finds ways to fight a white supremacist organization. [7] In a reality where vigilantes and superheroes save the day, the idea of one or two individuals taking on white supremacy seems less insurmountable. By meshing the fantasy genre with historical facts such as 22,000 people marching in a Madison Square Garden Nazi Rally in 1939, Lindelof establishes a world where Black people take on racial injustice in a way that feels authentic. Characters don’t simply defeat the big “bad guy” and move on to another with different motives. The true villains are racism, bigotry, and white supremacy personified – concepts so ingrained into the world of Watchmen and modern America that the battles are never the end of the war. Nevertheless, the fantasy gives audiences the occasional win to hold on to as they continue the fight for equality.

I neglected to put this in my review, but #LovecraftCountry does more to highlight the necessity of the Green Book than the bs movie that shares its name https://t.co/JhhSKzlraV

— Candice Frederick (@ReelTalker) August 17, 2020

In the first episode of Lovecraft Country titled “Sundown,” audiences are introduced to Uncle George’s Safe Negro Travel Guide. This book is a direct reference to the Negro Motorist Green Book created by Victor Hugo Green. [8] George’s guidebook is a tool to help Black families navigate different parts of the country during Jim Crow. He advises safe locations for dinner and good places to stop at night. He also gives readers information about the places to which they need to be weary, particularly sundown towns and counties. This episode emphasizes the importance of the guide when George, Leti, and Tic are chased out of town by a racist sheriff. He tells them that they are in a sundown county with only minutes to spare before sunset. [9] For many audiences, this examination into the Black travel guides corrects problems unaddressed by the Oscar-winning movie Green Book (Peter Farrelly, 2018).

Watchmen and Lovecraft Country: Re-educating White audiences

Me 🤚 I did NOT know about the Tulsa Massacre 1921 until I watched @Watchmen on HBO last night. We need to do better than this. https://t.co/Xgw3Ar8uKo

— 🐝 RCMhere (@RCMhere) October 22, 2019

After viewing the opening scene of Watchmen, viewers flooded social media with comments about the Tulsa Massacre. Many white viewers had no idea about the real atrocities experienced on Black Wall Street that day in Tulsa. The show gave its first of many history lessons. It showed the airplanes bombing the area as white men shot people on the street. This massacre, not Pearl Harbor, was the first time that Americans were terrorized with an aerial assault. [10] As many fans of the show pointed out on Twitter, this episode delivered a teachable moment in exploring a historical event often not explained or taught in history classes to white audiences.

One cool thing about the US education system is that I am consistently learning more about racist policies/events from TV shows than I ever did from textbooks. Heard about “sundown towns” in Lovecraft Country tonight. There’s one a few hours from me in Vidor, TX! 👍

— 🎃Spooky Brain Haver🎃 (@ParkerPSM) August 17, 2020

Lovecraft Country’s “Sundown” prompted some white viewers to look into the history of their towns and places that they previously traveled. It is easier to dismiss racial histories when they seem like they are far in the past. Lovecraft Country mostly takes place in the Chicago summer of 1955. As viewers looked online for information about past sundown towns, they realized that sundown towns still exist all over the country. Episodes like these now create spaces for white audiences to explore more contemporary ramifications to centuries of racial trauma inflicted on the Black community.

Expanding Jordan Peele’s canon on the small screen

Watchman is the first in a line of television series that models Jordan Peele’s canon of work in the horror/sci-fi genre for films. Get Out (2017) is his first critically acclaimed movie to genre bend in this way. Peele uses horror to illuminate the problems with neoliberal ideology that claims America is a post-racial society. With Get Out, Peele argues that this mindset is often a cover for racial and bigoted beliefs. [11] Peele then follows this up with Us (2019), using horror to explore how race and class are used to divide society. The tethered beings in the underground tunnels represent America’s attempt to hide the racial and economic foundations of this country. The longer it has to fester, the more likely it is to bubble up to the surface. [12] With his executive produced Candyman (2021), directed by African American director Nia DaCosta, Peele has expanded his canon to a trilogy that explores how communities, over time, develop urban legends to explain violence. With this forthcoming project, Peele and DaCosta wanted to examine the stories that communities tell themselves. [13]

Given the success of Peele’s films on the big screen and their appeal to both Black and white audiences in distinct ways, it is not surprising that Peele is spearheading and expanding this genre-bending approach within the sci-fi/horror/fantasy genres to the small screen. He serves as the co-executive producer of Lovecraft Country. HBO’s Watchmen – and now Lovecraft Country – expands Peele’s methodology into a serial televised medium by which audiences can slowly and more thoroughly confront past and present racial trauma, beyond a single film.

Black fans and sci-fi/horror/fantasy

Traditionally, the sci-fi, horror, and fantasy genres were not categories where Black fans could see themselves – whether in film or television. In science fiction, Black characters just weren’t there. The science fiction genre, at its core, delves into the infinite possibilities in the universe, yet rarely do any of those realities have Black characters. In the fantasy genre, Black characters are rarely given lead roles in productions of the same caliber as their white co-stars. Horror isn’t much better. Black characters are often killed off early in movies and given little to no character development before their untimely demise. With this in mind, people often view these genres as ones that do not attract Black fandom. However, this is simply not the case. Black fans have supported television shows and movies like Doctor Who, The Twilight Zone, and It long before they had quality representations of Black characters.

Watchmen and Lovecraft Country carved out areas in these genres for Black fandom to rally around characters made specifically with them in mind. These Black characters have depth and agency in a way that has been ignored on screen for decades. When done correctly, shows like these two prove that Black content is not only profitable to Black producers and actors, but they are culturally transforming for a generation starved of authentic Black portrayals.

Image Credits:

- Promotional image for HBO’s Lovecraft Country (left), Promotional image for HBO’s Watchmen (right)

- “It just reminds you how much pain our country was built on that we haven’t talked about.” – @ReginaKing from @watchmen tweet on June 20, 2020.

- “1 of my fave parts of tonight’s watchmen episode were the 2 newspaper clippings about the SOLD OUT nazi rally…” – @radseed from November 25, 2019 tweet.

- “I neglected to put this in my review, but #LovecraftCountry does more to highlight the necessity of the Green Book…” – @ReelTalker from August 16, 2020 tweet.

- “Me. I did NOT know about the Tulsa Massacre 1921 until I watched @Watchmen on HBO last night” – @RCMhere from October 22, 2019 tweet.

- “One cool thing about the US education system is that I am consistently learning more about racist policies/events from TV…” – @ParkerPSM from August 16, 2020 tweet.

- Watchmen (2019). (n.d.). Retrieved October 12, 2020, from https://www.metacritic.com/tv/watchmen-2019/season-1/user-reviews [↩]

- Watchmen: Season 1. (n.d.). Retrieved October 12, 2020, from https://www.rottentomatoes.com/tv/watchmen/s01 [↩]

- Jensen, J. (2005, October 21). ‘Watchmen’: An Oral History. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved October 12, 2020, from https://ew.com/books/2005/10/21/watchmen-oral-history/ [↩]

- VanDerWerff, E. (2019, October 20). HBO’s Watchmen tells stories about America’s racist past in America’s racist present. Vox. Retrieved October 12, 2020, from https://www.vox.com/culture/2019/10/20/20919750/watchmen-hbo-regina-king-review-damon-lindelof-race-policing [↩]

- Lindelof, D. (Writer), & Kassell, N. (Director). (2019, October 20). It’s Summer and We’re Running Out of Ice (Season 1, Episode 1). [TV series episode]. Watchmen. Home Box Office; DC Comics; Warner Bros Television; White Rabbit. [↩]

- Boger, J. (2018). Manipulations of Stereotypes and Horror Clichés to Criticize Post-Racial White Liberalism in Jordan Peele’s Get Out . The Graduate Review(3), 149-158. https://vc.bridgew.edu/grad_rev/vol3/iss1/22 [↩]

- Lindelof, D. (Writer), & Williams, S. (Director). (2019, November 24). This Extraordinary Being. (Season 1, Episode 6). [TV series episode]. Watchmen. Home Box Office; DC Comics; Warner Bros Television Studios; White Rabbit. [↩]

- Gooden, T. (2020, August 17). The Real History of LOVECRAFT COUNTRY’s Safe Negro Travel Guide. Nerdist. Retrieved October 12, 2020, from https://nerdist.com/article/lovecraft-country-safe-negro-travel-guide-history/ [↩]

- Green, M. (Writer), & Demange, Y. (Director). (2020, August 16). Sundown [Television series episode]. Lovecraft County. Home Box Office; Monkeypaw Productions; Bad Robot Productions; Warner Bros Television Studios. [↩]

- Pelley, S. (2020, June 14). Greenwood, 1921: One of the worst race massacres in American history. CBS News. Retrieved October 12, 2020, from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/greenwood-massacre-tulsa-oklahoma-1921-race-riot-60-minutes-2020-06-14/ [↩]

- Landsberg, A. (2018). Horror vérité: politics and history in Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017). Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, 32(5), 629–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2018.1500522 [↩]

- Wall, D. (2019). Film Review: Us. Black Camera, 11(1), 457-461. doi:10.2979/blackcamera.11.1.25 [↩]

- Reed, A. (2020, August 28). New scenes from ‘Candyman’ reveal hook-wielding horror at American Black Film Festival. USA Today. Retrieved October 12, 2020, from https://www.usatoday.com/story/entertainment/movies/2020/08/25/candyman-new-scenes-revealed-nia-dacosta-jordan-peele-horror-film/3433205001/ [↩]

Keep these 10 tips in mind and you’ll be publishing great blog content that attracts prospects and clients

in your niche market. After publishing, you can return anytime to edit the content blocks.

The content is meaty, multi-lingual, and timely. It

asks basic questions about who can define authenticity and quality in an art practice that was historically based in a specific cultural identity but is now being assimilated/exploited/expanded.

Diplomacy in particular was important in forming job

related skill, as it taught me very basic principles that apply in business as well as in international relations.

International stars like Pele captured attention on the airwaves.

It’s focusing my attention differently. I

dream of a time when we have as much attention and access to creative and

cultural activities as we do to athletics. Material needs

were important, but they needed so much more. I will be indulging in catching up with lots

of my favourite blogs (and updating my blog roll in the process), getting some crafty books out of the library plus doing

some more “serious” reading with my business hat on. In its early days, MoviePass seemed to be

trying to build a viable business model, and acquired some high profile venture capital

investors, but it was eventually acquired by Helios

and Matheson, a data analytics firm, in a transaction in August 2017.

It is Helios and Matheson, intent on giving both data

and analysis a bad name, that instituted the $10 a month for a movie-a-day subscription.

Watchman is the first in a line of television series that models Jordan Peele’s canon of work in the horror/sci-fi genre for films. Get Out (2017) is his first critically acclaimed movie to genre bend in this way. Peele uses horror to illuminate the problems with neoliberal ideology that claims America is a post-racial society. With Get Out, Peele argues that this mindset is often a cover for racial and bigoted beliefs. [11] Peele then follows this up with Us (2019), using horror to explore how race and class are used to divide society. The tethered beings in the underground tunnels represent America’s attempt to hide the racial and economic foundations of this country. The longer it has to fester, the more likely it is to bubble up to the surface. [12] With his executive produced Candyman (2021), directed by African American director Nia DaCosta, Peele has expanded his canon to a trilogy that explores how communities, over time, develop urban legends to explain violence. With this forthcoming project, Peele and DaCosta wanted to examine the stories that communities tell themselves. [13]

Given the success of Peele’s films on the big screen and their appeal to both Black and white audiences in distinct ways, it is not surprising that Peele is spearheading and expanding this genre-bending approach within the sci-fi/horror/fantasy genres to the small screen. He serves as the co-executive producer of Lovecraft Country. HBO’s Watchmen – and now Lovecraft Country – expands Peele’s methodology into a serial televised medium by which audiences can slowly and more thoroughly confront past and present racial trauma, beyond a single film.