Over*Flow: They Are Risen: Drive-In Distractions and Hallowed Ground Under Lockdown

David Church / Indiana University

Among the COVID-19 pandemic’s major disruptions to the entertainment industry, the shuttering of movie theaters across much of the world has been one of the most talked-about developments. Even at a time when popular reportage about box-office numbers does more to gloss over theatrical exhibition’s place as a loss leader compared to home-video distribution windows, the major Hollywood studios have either delayed their upcoming release slates, vastly foreshortened the theatrical window, or premiered a handful of new releases as video-on-demand (VOD) streaming rentals. Perhaps a foregone conclusion, this latter option ironically recalls the same strategies that art-cinema distributors have used for several decades to combat the decline of arthouse theaters—even as the “eventness” of these day-and-date rentals also suggests the longer tradition of pay-per-view’s (PPV) imagined viewing collectivities for boxing and wrestling events.[1]

Here in the United States, spring 2020 has witnessed a series of social-distancing restrictions (all of different severity or laxity, depending on the uneven rollout of local and state guidelines). Among many trade groups attempting to weather the lockdown, the National Association of Theatre Owners lobbied Congress to help keep shuttered theaters afloat through the multi-trillion-dollar COVID-19 relief bills. But these bailout calls from brick-and-mortar businesses have been counterbalanced, in part, by the forms of mobile privatization that cars and trucks have served for many Americans since the 1950s.[2] The curbside pickup of groceries, meals, and other essentials calls back to the 1950s rise of drive-in restaurants (minus the sociality); meanwhile, restaurant drive-thru windows have allowed other businesses to stay financially alive, and even drive-through COVID-19 testing facilities (where available) have been created to help foster more literal forms of survival.

In an ironic stroke of timing, however, America’s indoor theaters closed en masse just as its over 300 surviving drive-in theaters were slowly emerging from their winter hibernation—a fraction of which were allowed to re-open for business (subject to state and local restrictions), so long as attendees maintained social-distancing protocols by remaining in and around their vehicles. Even operating with reduced services (such as limited food sales and restroom access), drive-ins became almost the only theaters operating across the nation for weeks, with the admission price for a carload of family members comparable to a VOD rental ($19.99) of the same movies; families might still be isolated together, but with a welcome change of scenery.[3] This sudden demand for drive-ins has even led to the creation of pop-up theaters and calls for new construction of permanent drive-in theaters.

National news coverage of this unexpected revival for a decidedly “retro” exhibition style has tended to play up much of the same novelty value that drive-ins originally used to promote themselves back during their 1950s heyday, such as convenience, affordability, and family-friendly ambience—albeit now reframed around their scarcity in the streaming video era.[4] At a deeper level, however, car ownership is far more common in rural America than the high-speed internet access needed for streaming video platforms. Despite so much media coverage about the COVID-19 lockdown as a boon to Netflix, Hulu, and other major players in the streaming wars, the outsized attention paid to streaming services ignores that this luxury is not enjoyed by large chunks of the country, especially in more rural areas. Discussions of the so-called “digital divide” may now be less about total inaccessibility than very limited Internet functionality depending on one’s region and/or class status—hence it remains crucial to heed the affordances of older cinematic technologies like drive-in theaters when newer platforms are not viable options for accessing movies during the lockdown.

In a parallel development, some shuttered churches began holding drive-in services using the same shortwave FM transmitters that drive-in theaters use to channel sound through car speakers. Assembling their vehicle-bound congregants in the empty parking lots of stores and, in some cases, drive-in theaters themselves, churches have turned to both live and pre-recorded sermons, encouraging parishioners to honk their horns for “amens.” Indeed, the concept of the drive-in church dates back to the 1950s, when drive-in theaters were first used for evangelical purposes during daylight hours. Whereas some churches have turned to livestreaming services, drive-in sermons might be a better option for those unable to technologically access such content—much like the cinematic forms of distraction and comfort offered by drive-in movies. Adamant about holding services during Holy Week, some church leaders echoed President Trump’s delusional hopes to resurrect the economy by Easter Sunday, a potentially lucrative time for churches due to above-average holiday attendance. In some cases, though, local governments have attempted to shut down drive-in services or penalize attendees for violating bans on public assembly, leading to lawsuits over religious freedom.

Yet, the similarities between drive-in movies and drive-in church services would be merely a fluke were they not indicative of a larger politicization of public space during the crisis, with political conservatives and conservative-leaning areas less likely to heed social-distancing measures. Due to the lower land costs required for a permanent drive-in theater, they have best survived in areas whose lower population densities are often less conducive to high rates of COVID-19 transmission than large cities—the same non-urban areas also more likely to lean conservative. Scott Herring suggests, for example, that regional drive-ins became an unlikely site for the 1970s burgeoning of New Right politics by screening “hixploitation” films that romanticized rural white identity,[5] while I would argue that drive-ins’ latter-day reputation as sites of 1950s nostalgia can create imagined spaces of reactionary refuge from various forms of social turmoil that now include the COVID-19 threat. Indeed, nostalgizing drive-ins as populist sites runs the risk of nostalgizing the 1950s as a time when America was supposedly “great,” much as the less disciplined behaviors historically permitted by drive-in attendance can play into right-wing skepticism about social-distancing guidelines. Small wonder that conservative publication The Federalist nostalgically heralded the return of the drive-in theater as “good, clean, old-fashioned fun” for American families, only days after dangerously suggesting that “controlled voluntary infection” through “coronavirus parties” would help build herd immunity in order to re-open the economy sooner (never mind the lives lost in the process).

Much as the Trump administration has filed a statement of support in lawsuits against local crackdowns on drive-in church services, there is no shortage of people whose belief in some great reward beyond—whether a spiritual afterlife or thriving markets—should supposedly outweigh their social responsibility to the safety of nonbelievers. Of course, we should not presume that all people attending drive-in movies or church services have ideological reasons for doing so, beyond trying to maintain some sense of normalcy under extraordinary circumstances—yet, both types of drive-in events offer the semblance of community in semi-isolation, while still warding off different sorts of invisible evils. Faced with the existential threat of COVID-19, there are plenty of Americans who might not have ready access to the same means of soothing themselves in such troubling times—but whether attending a drive-in movie or drive-in church service is ultimately any more useful than a Netflix binge or VOD rental remains a question of faith, if not politics.

Image Credits:

- Easter 2020 church service at Becky’s Drive-In Theatre (Walnutport, PA)

- 1950s “Autoscope” drive-in system

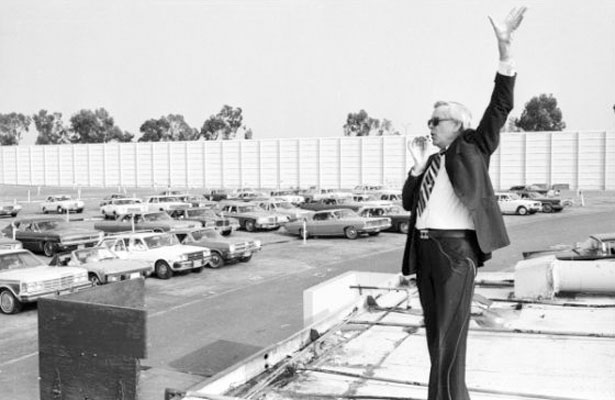

- Pioneer of drive-in church services, Rev. Robert Schuller, at the Orange Drive-in Theatre, 1978

- News coverage of Easter drive-in church service, Walnutport, PA (MSNBC, April 12, 2020)

- WWE’s WrestleMania 36, for instance, aired on April 4-5, 2020, but the PPV event’s conspicuous lack of cheering audiences in the stands worked against PPV subscribers’ sense of belonging to a collective viewing audience. On the shift to VOD platforms by art cinema distributors, also see Lucas Hilderbrand, “The Art of Distribution: Video on Demand,” Film Quarterly 64, no. 2 (2010): 24-28. [↩]

- During the 1957-58 H2N2 flu pandemic, movie theaters were not shuttered, but attendance dropped by 25-50% in large cities as people stayed home to avoid infection. In an interesting connection to the boom in streaming services during the COVID-19 pandemic, industry wags debated whether to instead blame the box-office drop-off on the growth of home movie viewing, since October 1957 marked “the first time that daily audience for vintage productions on TV exceeded a full week’s attendance at theaters.” See “Current Alibi: Flu,” Variety, October 23, 1957; and “Flu Cost 10-Mil Tix—Sindlinger,” Variety, November 6, 1957. [↩]

- For a historical example of this overlap between domestic and public viewing, see the “Autoscope” system, a short-lived variety of 1950s drive-in theater, in which each car, parked in a circular formation, had its own small, individual rear-projection screen served through optical refraction. [↩]

- Also see David Church, Grindhouse Nostalgia: Memory, Home Video, and Exploitation Film Fandom (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015), chp. 1. [↩]

- Scott Herring, “‘Hixploitation’ Cinema, Regional Drive-ins, and the Cultural Emergence of a Queer New Right,” GLQ 20, no. 1-2 (2014): 95-113. [↩]

Very insightful!

Thanks for sharing this great information.

Thanks for the post, it’s really sad that we are all facing this pandemic and no one knows when it will end.

So sad that we’re all facing this pandemic and no one knows when it’ll end.

Great information, thanks for the share.

Very interesting article!

Nice site

This page is really interesting

This page is really really interesting