Gender and the Soundscape of Major League Baseball

Kathy Cacace / The University of Texas at Austin

Perhaps the most beloved female presence discussed in Curt Smith’s door-stopper reference on baseball broadcasting, Voices of the Game, is a woman who never existed. Aunt Minnie was improvised in the heat of a game in 1938 by the Pittsburgh Pirates’ first radio announcer Rosey Rowswell. A hard-hit Pirate homer flew past the stands of Forbes Field and, as Smith quotes the broadcast, “Rosey stood up and implored, ‘Get upstairs Aunt Minnie, and raise the window! Here she [the baseball] comes!’ Seconds later to Rowswell’s rear, an assistant shattered a pane of glass; to partisans at home, the broken glass meant Aunt Minnie’s window. ‘That’s too bad,’ Rosey sobbed. ‘She tripped over a garden hose! Aunt Minnie never made it!'” [1] Poor Aunt Minnie’s windows were routinely smashed over the course of Rowswell’s career—he once snatched the microphone from Bing Crosby to implore Aunt Minnie to throw open her sash—and over the years a few women in Pittsburgh even claimed to be Aunt Minnie. Fellow Pittsburgh broadcaster Bob Prince insists that women liked the Aunt Minnie home run call “especially—it drew them out as fans.” [2]

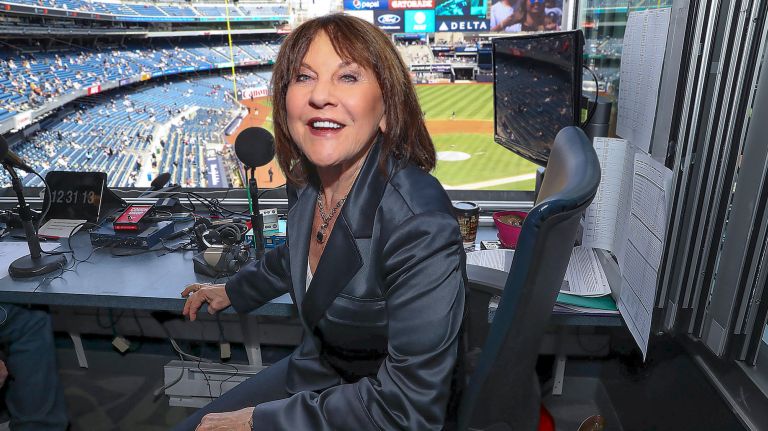

Yet Aunt Minnie, however fictional, never spoke a word on the air. Her absent presence typifies the relationship between women and baseball broadcast history. Smith himself omits women’s voices almost entirely from Voices of the Game. He does not discuss Betty Caywood, the first woman hired to do color commentary (as a stunt) in 1964, and dedicates just a dismissive half line to the “shrill-voiced Mary Shane,” the first true female announcer who called half a season alongside Harry Caray in 1977. And while Smith published his book more than 30 years ago, women’s voices remain rare and contentious in baseball broadcasting. Jonathan Fraser Light reports that the first female stadium public address announcer was not hired until 1993, when Sherry Davis had to produce a personal scorebook she had kept for years to prove to the San Francisco Giants that she was qualified for the position. [3] New York Yankees broadcaster Suzyn Waldman was sent feces and used condoms in the mail during the 1980s and 1990s and received so many death threats she had to be protected by stadium security. Jessica Mendoza, former Olympic softball player and first female baseball analyst for ESPN, received abusive and misogynist comments on Twitter from men, including from another sports broadcaster, during her first playoff game in 2015. More than four years later, she still reports having to wait a day and a half after a game for online vitriol to die down so she can check her social media accounts.

Baseball’s soundscape is a crucial facet of the sport’s relationship to gender. It was mediatized through the radio, and this process was spurred at least in part by a desire to speak to (but not through) women during the 1920s and 1930s. Baseball media scholar James Walker found that team owners were initially divided about whether to broadcast games on the radio, believing that it would eat into ticket sales. However, “a few forward-thinking owners saw radio as a positive promotional device that could sell baseball to new customers” who could listen to day games. [4] That audience was women, specifically housewives, and their young children. Radio also provided a template for baseball broadcasts that televised games still hew to closely: a man or small group of men filling the long stretches between moments of excitement with oral storytelling. Though the booth remains a nearly impenetrable audio enclave for women, a relatively recent effort to enliven and personalize the game has given female voices an unlikely point of entry into baseball’s greater soundscape. [5]

Walk-up music is a short audio clip chosen by a (home team) player and piped through the stadium as he approaches either home plate for his at bat or the pitcher’s mound. The origins of walk-up music are fuzzy as stadium organists have performed clever, punny songs for select players for decades, but the practice became widespread in the 1990s. Walk-up music is frequently a song meant to put a player in a confident mindset for a stressful situation—hard rock remains a popular choice—but its function as individual speech makes it a more interesting phenomenon than it may first appear. A player’s song may change throughout the season, for example, in response to an offensive slump or current events. Ultimately, the choice of music offers the rare chance during a team sport for a player to express something of his personality and point of view. In this way, walk-up music becomes a moment of communication and intimacy between fans and players.

Major League Baseball keeps a database of current walk-up music choices. As of this article’s publication, thirty players chose songs with audible female vocals. I have casually monitored this database for a few seasons and have observed a gradual upward trend in female vocalists, and suspect that these thirty selections are an all-time high. While this still represents only 4% of active players, each player might take the mound several times in a game and teams like the Dodgers and Brewers have more than one player whose music contains a female voice, potentially shifting a game’s overall soundscape in small but meaningful ways. Women’s voices may not be permitted to carry much authority in baseball, but their increasing inclusion as walk-up artists demonstrates the profound cultural meanings they communicate outside the confines of the broadcast booth. For example, José Abreu and Aledmys Diaz are both Cuban players who chose Celia Cruz songs, highlighting her status as a powerful icon able to perform their love for their heritage. The relatively recent inclusion of female hip hop, R&B, and reggaeton artists like Cardi B., Nicki Minaj, Natti Natasha, and Rihanna signals a shift within the production and reception of these genres, and therefore a broadening cultural conception of who can embody the peacocking sort of confidence that walk-up songs are often selected to evoke.

Players who choose overtly teen-coded pop songs are still subject to gender-based scrutiny by the baseball press. Troy Tulowitzki chose Miley Cyrus’s “Party in the USA” for his 2010 walk-up song. A local journalist was so surprised the “tough-as-nails Tulo went with Miley, I just assumed he lost a bet with Jason Giambi or something.” Tulowitzki, however, explained that he simply liked the song and chose it to please young fans in the stadium. Similarly, a Twitter user who used to track plate music was quoted in 2015 as feeling suspicious when “some of these guys will have a Taylor Swift song, someone will have Katy Perry … I’m always curious why they chose a particular song — was it something they picked, or did they lose a bet?” That choosing to play fifteen seconds of music by a young female pop star continues to set off the masculinity red alert within baseball journalism betrays the entrenched conservatism of the institution. [6] Even so, I am inclined as a female baseball fan to see walk-up songs as a measured case of agency begetting agency, one tiny sound bite at a time. Baseball players are racially and culturally varied group whose subjectivities challenge the hegemonic white imaginary of baseball as America’s game. Where they are given a choice to speak for themselves, they do so through more discordant, more diverse, and more interesting musical registers than a single anglophone baritone crackling out over the AM waves.

Image Credits:

1. Newsday

2. YouTube

3. Author’s photograph

Please feel free to comment.

- Curt Smith, Voices of the Game (South Bend: Diamond Communications, 1987): 77. [↩]

- Smith, Voices of the Game, 79. [↩]

- Jonathan Fraser Light, The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball, (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 1997). [↩]

- James R. Walker, “The Baseball-Radio War, 1931-1935,” in NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture 19, no. 2 (Spring 2011): 53. [↩]

- Broadcasting may be changing more quickly at the minor league level. This April, Melanie Newman and Suzie Cool became the first all-female booth to call a game. [↩]

- Though a full exploration of the following point falls outside the scope of this short article, it is still important to note that it is primarily the selection of music by white female musicians that seems to be beyond the pale. This resonates with long-standing and destructive beliefs in American culture about white women as paragons of femininity. [↩]