“Driven By Hustle”: Uber Presents, Lyft Entertainment, and Rideshare Media Production

Eric Forthun / University of Texas at Austin

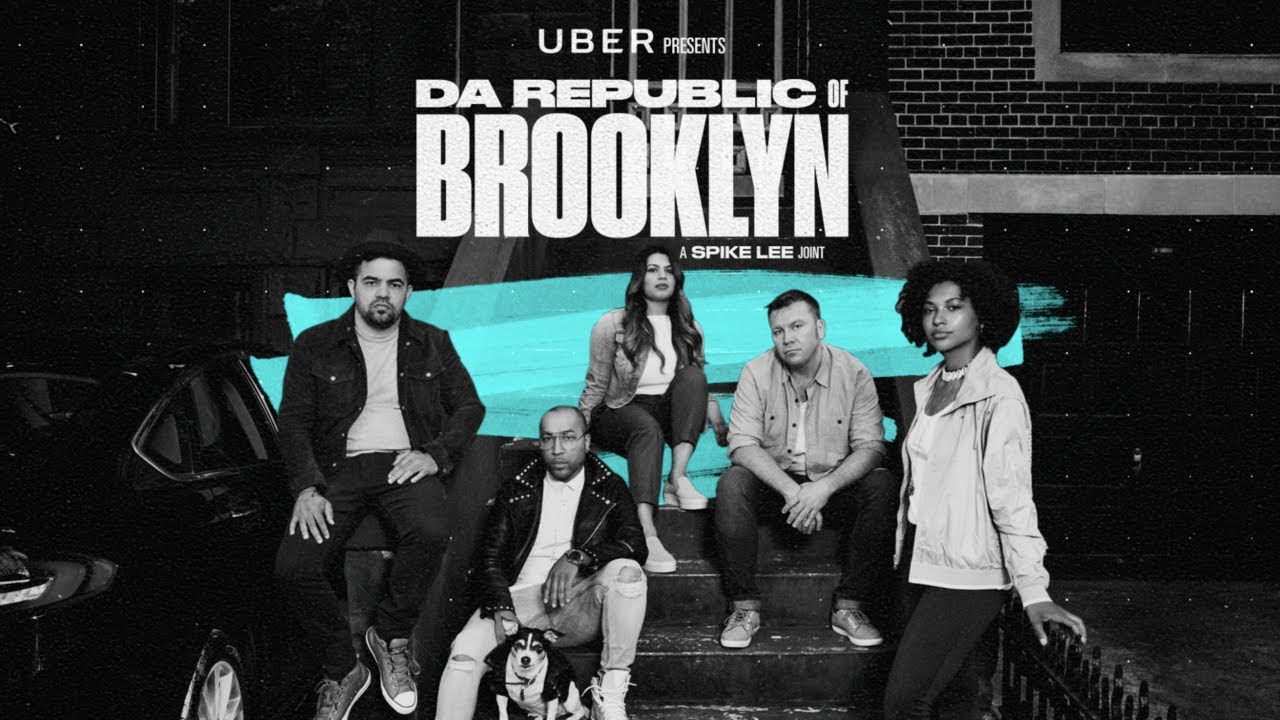

On July 11, 2018, Uber released five short films “driven by hustle” in a series called Da Republic of Brooklyn. Billed as a “Spike Lee Joint,” Uber Presents’ first original production highlights the backgrounds and stories of those contractors hand-selected by Lee himself from Uber’s thousands of Brooklyn drivers and delivery partners. All of them are linked not just through their difficult upbringings and connections to the titular New York borough, but also their part-time work for Uber and UberEats. These services provide flexibility (an oft-cited rideshare talking point) for these workers to “hustle” on the side and achieve their goals. This unstable form of labor is almost always positioned as an opportunity for, and not a burden to, drivers.

Through each episode of Da Republic of Brooklyn, the series increasingly downplays Uber’s role in these people’s lives, instead positioning Uber as emblematic of how, as Domingo explains in his episode, “the Brooklyn hustle can be brought anywhere.” Sunny, an aspiring model and actress, remarks that Uber allows her to have “such a flexible, open schedule”; Rodney, an artist and restorationist, explains how Uber grants him “clarity” and gives him “the focus” he needs to find inspiration in his other work; and Keith, a driver who wants to open a doggie day care center, remarks that Uber brings “no stress” because it provides the freedom to be “your own boss” who decides “how much you want to work.” For these drivers, Uber is not their primary occupation—as many ads for rideshare companies in 2017 and 2018 noted, drivers should “get their side hustle on” to switch between earning and “chilling.”

The gig economy’s “side hustle” has rapidly emerged as a necessity for many Americans, particularly as wages stagnate and the American economy overwhelmingly favors the interests of the wealthy. The “hustle” has been engrained in the rideshare industry’s ethos since its inception. A recent study showed that 48 percent of millennials say they earn extra income, pay down debt, or boost their savings through gig economy work, and the working issues that arise are often aimed at specific companies rather than the larger gig economy’s precarious and often predatory treatment of its workers. Even scripted series and films such as Insecure (HBO, 2017-) and Stuber (2019) double down on how Lyft and Uber drivers, respectively, frequently work part-time to supplement their other sources of income because it is difficult to make ends meet on just one job. I, too, drive for both Uber and Lyft part-time to make ends meet, and often find myself unconsciously recycling narratives about these companies allowing me to earn a lot when I want and as often as I want.

Da Republic of Brooklyn perpetuates the ubiquitous claim that “hustling” allows workers to achieve their own goals, even as that practice requires workers to opt out of financial security such as 401ks, work-provided health insurance, or substantial stock options in rideshare companies’ newly launched IPOs. Lyft and Uber are both incredibly valuable companies (valued around $24 and $74 billion, respectively) that continue to decrease driver bonuses, decrease mileage pay, and hemorrhage capital under the guise of staying competitive. Lee’s series does not examine how much the showcased drivers make per hour, and Uber only notes how long they have been working for the company on the information panels on Uber Presents’ website. This presentation distances Uber from its status as an employer and instead grants the rideshare company its own opportunity to position its labor as a side hustle for “partners” to eventually achieve seemingly worthier and more fulfilling career goals.

For full-time drivers, working for these companies is “becoming financially untenable,” as average monthly earnings declined nearly 50 percent over the last five years as Uber’s work force increased from 160,000 Americans in 2014 to over 900,000 by late 2018. Uber, Lyft, and other gig economy employers’ deliberate decision to classify their employees as “partners” and, legally, as “independent contractors” allows companies to avoid proper compensation for its full-time workers in order to maximize profits. Just five months after the series debuted, New York City officials passed a minimum pay rate around $17.22 per hour for drivers on ride-hailing apps “to make sure drivers can earn a decent living.” The series’ debut in the months prior to these legislative changes is likely not coincidental, but rather part of Uber’s larger mission to market itself in a friendlier, less corporate light in the wake of sexual harassment scandals and their former CEO’s beratement of a long-time Uber driver for not taking “responsibility” for his own actions as drivers’ fares were cut.

Lyft, meanwhile, has always presented itself as the more colorful and friendlier rideshare company, and its original content advances this positioning. Lyft Entertainment is a media production company that began with lighthearted, celebrity-driven fare such as “Undercover Lyft,” with the likes of Kevin Hart, Danica Patrick, and Jason Sudeikis riding in disguise behind the wheel. These videos generated hundreds of millions of YouTube views, in stark contrast to Da Republic of Brooklyn‘s two million viewers for five videos. Lyft Entertainment has found tremendous success in the online space and recently ventured into original co-productions. The company brought back Billy on the Street (Fuse/TruTV, 2011-17; YouTube, 2018-) with Funny or Die, and premiered East of La Brea at 2019’s SXSW Festival. The latter is a co-production with Paul Feig’s Powderkeg, a company that aims “to tell the stories of talented, emerging and underrepresented voices in comedy” (Fleming 2019). Feig’s series, like Billy on the Street, has no obvious connection to Lyft’s products, but it carries the diverse and positive image that Lyft often produces.

While Uber’s series more explicitly promotes the “hustle” of part-time work, Uber and Lyft’s media production coalesces around their depictions of a diverse, ambitious labor force. These companies and other technology conglomerates have faced considerable scrutiny and criticism for their racist and sexist practices, but these series act as a forward-facing promotion of rideshare companies’ progressiveness. The entrance of rideshare companies into the original content space might seem like another form of burning through venture capital (which it is), but it also enables these companies to “inch away” from the “significant criticism” they have faced, much like Facebook and Twitter faced in the wake of Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election [1]. The production of series by and about marginalized voices is a welcome shift by the technology industry, even if it outwardly presents as self-aggrandizing and a distraction from more pervasively harmful practices.

Increasingly, other technology, software, and social media companies are launching or acquiring media production arms as a means of retaining online users, selling more lucrative advertising space, and guiding how users find and engage with online media. For social media companies in particular, the “stronger push into original content is an attempt to more directly benefit from activity already taking place on its platforms.” [2] Facebook launched Facebook Watch in August of 2017, producing dozens of original programs ranging in cost from $10,000 to over $1 million an episode, with early reports that they would be willing to spend $3-4 million per episode in order to place the service on equal footing with competitors. Apple is finally launching Apple TV+ in fall of 2019, with the intention of the service competing with Netflix at original film programming on an awards level. These companies will more than likely use these services to not just keep users on their respective platforms and devices, but also to combat their potentially negative publicity along the way, like Lyft and Uber.

Whether Uber Presents or Lyft Entertainment will launch successful scripted programming in this crowded media landscape remains to be seen. However, these services will likely continue to benefit from producing polished promotional materials that perpetuate the harmful narrative that these companies are merely opportunities for “hustling” and important sites of diversity.

Image Credits:

1. Author’s screengrab from YouTube.

2. Author’s screengrab.

3. Photo from Drew Angerer, Getty Images, in New York Magazine article.

4. Author’s screengrab.

- Barker, Cory. 2018. “Facebook, Twitter, and the Pivot to Original Content: From Social TV to TV on Social.” In “Social TV Fandom and the Media Industries,” edited by Myles McNutt, special issue, Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 26. http://dx.doi.org/10.3983/twc.2018.1291. [↩]

- Barker, Cory. 2018. “Facebook, Twitter, and the Pivot to Original Content: From Social TV to TV on Social.” In “Social TV Fandom and the Media Industries,” edited by Myles McNutt, special issue, Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 26. http://dx.doi.org/10.3983/twc.2018.1291. [↩]