The Devil in the Details: User Tracking Is Hurting More Than Our Privacy, It’s Doing Serious Damage to Public-Interest Media, Too.

Josh Braun / UMass Amherst

As I write this, my social media feeds are consumed by the furor resulting from Jeff Bezos’s open letter accusing The National Enquirer’s parent company, AMI, of attempting to extort him over leaked photographs from his affair. While much of the commentary rightly focuses on issues of digitally-enabled blackmail, Slate tech reporter April Glaser simultaneously muses at the irony of a privacy scandal befalling a tech CEO who’s garnered notoriety for “actively building a surveillance state.”

A few weeks on from “Data Privacy Day,” the international holiday aimed at promoting better protection for consumers’ data, the Bezos story is just one of many to raise questions about the individual right to privacy in the digital era. It follows closely on the heels of Facebook’s latest scandal—Apple pulled the company’s services from its app store after the revelation Facebook was paying teenagers to install tracking software on their phones—and years after a ProPublica report that Google had quietly abandoned its ban on collecting personally identifiable tracking data on its users. [1] Other recent reporting discusses how location information collected from our phones has found its way into the hands third parties ranging from robocallers to bounty hunters, raising deep concerns about individual privacy, personal safety, and even national security. [2]

As data privacy (or lack thereof) has begun to take on the dimensions of a crisis, another much-discussed emergency has been unfolding in parallel: the economic collapse of ad-supported digital journalism. Following a series of layoffs at news organizations ranging from TechCrunch to HuffPo to BuzzFeed and Gannett, respected tech columnist Farhad Manjoo wrote in The New York Times, “it would be a mistake to regard these cuts as the ordinary chop of a long-roiling digital media sea. Instead, they are a devastation. The cause of each company’s troubles may be distinct, but collectively the blood bath points to the same underlying market pathology: the inability of the digital advertising business to make much meaningful room for anyone but monopolistic tech giants.” Two days later, Vice cut 250 more journalism jobs, or 10 percent of its workforce.

This rash of cuts is especially painful, given that “digital-native newsrooms” were only recently celebrated as one of the few areas in American journalism to have added jobs over the course of a decade-long 25 percent decline in employment led by steady layoffs at traditional newspapers. [4]

These two crucial problems—the erosion of digital privacy and the revenue crisis in American journalism—have tended to be discussed as distinct issues. They are not. [5] Rather, they spring from a common origin and, to paraphrase Thoreau, in solving them we would do better to strike at the root than to hack at the branches. [6]

It is a commonplace that advertising pays for most of the free services we use on the the internet. The viral quotation from Jeff Hammerbacher, “The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads,” sums up much about the direction online business models have taken. And the solution that has been settled upon is programmatic advertising.

Programmatic advertising takes a number of forms, but generally speaking, in the fraction of a second that it takes a webpage or an app to load on your screen, an automated auction is being held for your attention based on tracking data that has been collected about you. The publisher puts up ad space for sale, brands put in competing bids to place an ad in the space, and intermediaries called ad tech firms handle all the transaction details. By the time the content you requested finishes loading, the auction winner’s ad appears on your screen alongside it.

While the most prominent news organizations, like The New York Times or The Economist, may still do a brisk business directly with branded advertisers, a vast number of other news organizations rely far more heavily on programmatic advertising exchanges to sell their inventory, competing not just with other news organizations, but with blogs, web forums, recipe sites, online games, and any other website or app that sells ad space in programmatic exchanges. This dramatically drives down the cost of ads and hence the revenue going to publishers.

Moreover, these transactions are often focused tightly around reaching particular consumers to the near exclusion of editorial context. To give one example, all of us have experienced “retargeted” advertising—view a suitcase on a retailer’s website and ads for the same piece of luggage follow you across the web for days or weeks.

As Malthouse, Maslowska, and Franks put it, programmatic advertising separates “the value of the content product from the audience product.” [7] Couldry and Turow argue that for traditionally ad-supported news organizations, continuing to chase down advertising revenue in this new environment is thoroughly corrupting. [8] As advertisers begin pursuing users with particular behavioral profiles, while paying less and less attention to the actual publications they’re visiting, publishers can no longer rely as they once did on the quality of their work. Rather, they must increasingly play the role of data brokers, participating in user surveillance and producing increasingly personalized and/or shopper-friendly content that bins visitors neatly into behavioral profiles that will better draw the bids of advertisers—advertisers that now, at least in comparison to days past, pay scant attention to the name on a site’s masthead.

In the days of contextual advertising, ads for suitcases might best be placed in travel magazines. Under the user-tracking paradigm, not only do brands no longer need to rely on particular publications to reach the consumers they’ve identified as desirable, there is now a perverse incentive to place ads on the least reputable sites, since these are the locations where users’ attention can be bought most cheaply. This has led to a boom in clickbait-driven webpages, selling cheap ad space against vapid or plagiarized content focused around miracle diets and strange cosmetic trends. During the 2016 U.S. election, “fake news” did particularly well as a variant of clickbait and thus became a profit-center for scammers.

I don’t use the term “scammers” loosely here—Jessica Eklund and I recently published a study in which we examined disfunction in the programmatic advertising industry. [10] Industry executives explained that many hoax news sites were fronts for outright fraud, ginning up page views with bots and click workers and selling them to advertisers for a profit. Legitimate visitors to these sites were welcome, of course, but often their main value was confusing fraud-detection mechanisms by pushing down the ratio of automated to human traffic.

In short, it might be fair to expect news organizations to endure stiffer competition from new corners—not simply blogs or Craigslist, but gaming apps and recipe sites. However, in the current market, legitimate journalism is competing for ad dollars with sites engaged in aggressive fraud, sometimes with the assistance of ad tech companies themselves. Along with related enterprises like fake traffic generation, these siphon billions of dollars out of the advertising market annually [11], contributing to the larger problem of market failure [12] in contemporary journalism.

To review, then, the massive system of commercial surveillance we see online not only impacts us in terms of privacy, safety, and security, it has dramatically increased the amount of information pollution [13] in the public sphere, gutting news budgets—and hence newsrooms—by driving down the amount paid for ads, turning trusted news organizations into data brokers that produce less civically valuable content, dramatically incentivizing the creation of clickbait and outright disinformation, and kindling remarkable volumes of fraudulent activity that simultaneously fleeces advertisers and diverts hefty amounts of money away from public-interest media.

One recent survey indicated that a sizable majority of the American public already sees the collection of their data in the service of targeted advertising as unethical. [14] I imagine they might feel even more strongly about the issue were it more commonly linked with dramatic declines in the health of public-interest media. As we witness the introduction of digital privacy policy conversations and frameworks, whether the GDPR in Europe or bills proposed in individual states here in the U.S., it’s time to begin examining commercial surveillance not just as a privacy issue, but as a notable threat to our media institutions and public discourse.

Image Credits:

1. With the attention economy in full swing…

2. A marketing screenshot for the Android launcher app…

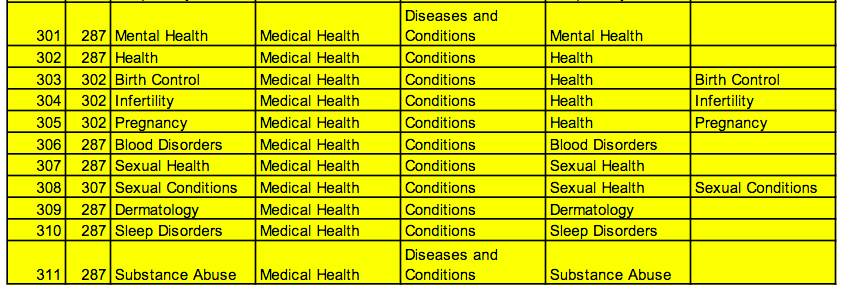

3. Screenshot from a document prepared by Brave…

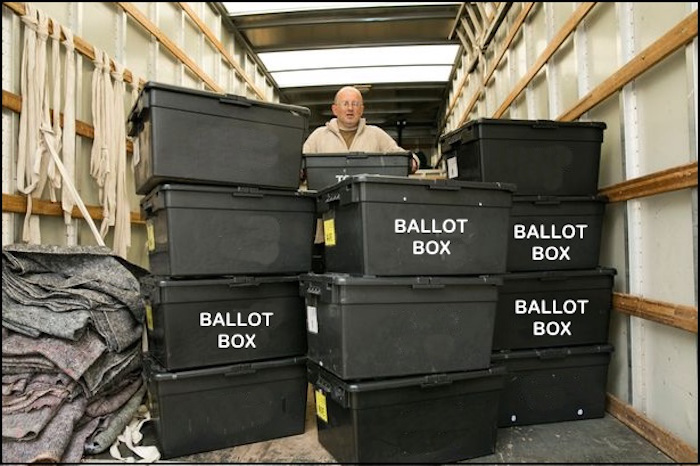

4. Originally from the Birmingham Mail, this image was appropriated by a hoax news article….

- Particularly when it comes to Facebook, the hits just keep on coming, fast enough that I decided it’d be unwise to try to keep updating this piece during the proofing process. Editorial: Facebook, Zuckerberg’s sins now include preying on teens. (2019, February 5). The Mercury News. Retrieved from https://www.mercurynews.com/2019/02/05/editorial-facebook-2/; Angwin, J. (2016, October 21). Google has quietly dropped ban on personally identifiable web tracking. ProPublica. Retrieved from https://www.propublica.org/article/google-has-quietly-dropped-ban-on-personally-identifiable-web-tracking. [↩]

- Vogt, P.J., Goldman, A., Marchetti, D., and Bennin, P. (Hosts.) (2019, January 31). Robocall: Bang bang [Podcast episode]. Reply All. Retrieved from https://www.gimletmedia.com/reply-all/135-the-robocall-conundrum#episode-player; Cox, Joseph. (2019, February 6). Hundreds of bounty hunters had access to AT&T, T-Mobile, and Sprint customer location data for years. Motherboard. Retrieved from https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/43z3dn/hundreds-bounty-hunters-att-tmobile-sprint-customer-location-data-years; Valentino-DeVries, J., Singer, N., Keller, M.H., and Krolik, A. (2018, December 10). Your apps know where you were last night, and they’re not keeping it secret. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/12/10/business/location-data-privacy-apps.html [↩]

- Silverman, C. (2018, October 23). Apps installed on millions of Android phones tracked user behavior to execute a multimillion-dollar ad fraud scheme. Buzzfeed. Retrieved from https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/how-a-massive-ad-fraud-scheme-exploited-android-phones-to [↩]

- Grieco, E. (2018, July 30). Newsroom employment dropped nearly a quarter in less than 10 years, with greatest decline at newspapers. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/07/30/newsroom-employment-dropped-nearly-a-quarter-in-less-than-10-years-with-greatest-decline-at-newspapers [↩]

- Ryan, J. (2019). The adtech crisis and disinformation [Lecture video]. Vimeo. Retrieved from https://vimeo.com/317245633. [↩]

- Thoreau, H.D. (1910/1854). Walden. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell & Co., p.98 [↩]

- Malthouse, E.C., Maslowska, E., and Franks, J. (2018). The role of big data in programmatic TV advertising. In V. Cauberghe, L. Hudders, and M. Eisend (Eds.), Advances in Advertising Research IX . (pp. 29–42). Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer. p. 32. [↩]

- Couldry, N. and Turow, J. (2014). Advertising, big data, and the clearance of the public realm. International Journal of Communication, 8, 1710–1726. [↩]

- Shane, S. (2017, January 18). From headline to photograph, a fake news masterpiece. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/18/us/fake-news-hillary-clinton-cameron-harris.html. [↩]

- Braun, J.A. and Eklund, J.L. (2019) Fake news, real money: Ad tech platforms, profit-driven hoaxes, and the business of journalism. Digital Journalism, 7(1), 1–21. [↩]

- Fulgoni, G. (2016). Fraud in digital advertising. Journal of Advertising Research, 56(2): 122–125. [↩]

- Pickard, V. (2015). America’s battle for media democracy. New York: Cambridge. [↩]

- Wardle, C., and Derakhshan, H. (2017). Information disorder. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Retrieved from https://firstdraftnews.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/PREMS-162317-GBR-2018-Report-de%CC%81sinformation-1.pdf [↩]

- RSA. (2019). RSA data privacy & security survey [Report]. Bedford, MA: Author. [↩]

Thank you so much I am helpful through this article.

Pingback: How the Adtech Market Incentivizes Profit-Driven Disinformation -

Very helpful information for me. Thank you for share this

Thanks a lot for this great article.

thanks for this great post.

This Information Is Very Helpful For Me Thanks For Sharing

Hey , its nice article , thanks for sharing with us

this is great thanks for sharing.

2019 GTA Vice City Cheats PC

Great shared. Thanks

interesting blog. really provide this blog helpful information everytime.

I am so much pleased to read your article. I just love this post. Here all information seems to be very resourceful and knowledgeable for everyone.

This is one of the finest post i have ever seen. The information is genuine and relatable . We are really grateful for your blog post.

Thank you for your info keep share with us

That is an awesome submit I seen. I should because of you to extent it. It is most likely what I needed to see seek in future you will proceed after sharing such an outstanding submit. I’m exceptionally started up to uncover it to each body

This is one of the finest post i have ever seen. The information is genuine and relatable . We are really grateful for your blog post.

Excellent information providing by your post thanks for sharing! i really to read it!

Excellent information providing by your post thanks for sharing! i really to read it!

this blog helpful information everytime.

Very informative article, really like the way you explain it.

really nice article

This article completely match my expectation and the variety of our information. It is very helpful for me.

This was a really wonderful post. Thank you for providing these details.

Hi Thank you so much for this useful and helpful guide to know more

This was a really wonderful post. Thank you for providing these details.

Hey, I really like this blog and it was very helpful for me to thank you so much. Also, check out our blog.

very informative article, really like the way you explain it.

Great information, thanks for sharing it with us

Thanks for sharing valuable information

Thanks For playing game with us Thank you man.

Great information, thanks for sharing it with us

Track your online parcels.

This is a best way for tracking

nice post

nice post

thanks for share :)

good information :)

Michael Letts is the Founder, President, and CEO of In-Vest USA, a national grassroots non-profit organization.

It’s always a pleasure seeing, and I hope you continues to work hard.

best way for tracking.. Great Information

amazing post on the tracking happening nowadays..Thanks for providing this valuable information. I look forward to more such informative posts.

These days no one’s data is safe. I’m impressed with the content of this post. Keep it up pal.

can someone plz explain what is this?

Nice Post Useful Information ..!

Internet advertising is a commonplace, and most of the services we can use for free are paid for by advertising.