Posting Up at Pigalle: The Online and Offline Worlds of Branded Basketball

Courtney M. Cox / University of Southern California

I am standing on Rue Duperré, a narrow street in a Paris neighborhood. The only way I can describe it is beautifully crumbly—well-preserved but a bit old and dreary, especially on a cold winter day. And then, in the midst of the crumbly, I reach it—yellows, purples, and blues swirl around me, beckoning me inside the gate. There I find a group of children playing a game of pickup basketball while a model and her glam squad cluster in the corner, waiting for a stoppage in play to set up a photo shoot.

This is the famous Pigalle court—made popular locally by its vivid color in the midst of its drab concrete surroundings, and known globally in small rectangular form through thousands of Instagram posts circulated constantly. Named for the popular streetwear brand, the colorful court offers a public sporting space emblazoned with abstract expressionism and perhaps more importantly, Pigalle’s name and logo.

Over the past few years, Pigalle has used the court to expand its streetwear reach, developing Pigalle Basketball, an offshoot which caters to the “athleisure” market and the ever-growing National Basketball Association (NBA) fanbase in France. Across the street from the court, the store is tucked into the neighborhood, a simple chalkboard sign denoting its existence steps away from the Insta-iconic space.

The creators behind the court, Ill-Studio, Pigalle, and Nike, describe it as an exploration of “the relationship between sport, art and culture and its emergence as a powerful socio-cultural indicator of a period in time.” This particular time for brick-and-mortar stores is complicated as Amazon and other companies offer the convenience of curated suggestions, rapid shipping, and delivery options, which include placing items in your car, at your door, or even inside your home, all with a click of a button. This, in tandem with the rise of streaming services, video on demand (VOD), and DVR, allows viewers to fast forward past commercials or eschew them all together for a monthly fee. To compete with e-commerce and the loss of many traditional advertising platforms, many companies have employed the experiential, with pop-up shops, limited editions, and interactive events that offer a built-in, free advertising component for those posting on social media. The visual appeal of these viral marketing ploys can affect even the most discerning, critical scholar.

It was perhaps not until I reached WiFi to post this photo that I realized my role in what David Harvey has termed the “time-space compression”—the constantly accelerated nature of the production, exchange, and consumption of goods, services, and experiences—that remains a key aspect of postmodernism as he understands it. He writes in The Condition of Postmodernity that “The mobilization of fashion in mass (as opposed to elite) markets provided a means to accelerate the pace of consumption not only in clothing, ornament, and decoration but also across a wide swathe of life-styles and recreational activities.” [1] He argues that a secondary trend in consumption is a move away from the consumption of goods and into the consumption of services, including “entertainments, spectacles, happenings, and distractions.” [2] With Pigalle, these experiences of consumption can occur over the course of a pickup game of basketball or with a scroll across Instagram. Before arriving in Paris, I was already aware of the court and specifically planned to view it in the same way one would plan to see the Eiffel Tower. My readiness to capture my pilgrimage to Pigalle and share throughout my Instagram network reflects Harvey’s notion of the “consumer turnover time,” the rapid nature of spreading images, as the image of Pigalle (and accompanying geotag) continues to serve as an identity-establishing emblem for those marketing public consumption of the space. [3] Pigalle Basketball is not merely a place to shop, it is a sight to behold.

Advertising, according to Harvey is no longer built around the traditional model of informing or promoting. Rather, niche marketing attempts to appeal to desires or taste through images that may not have anything to do with the product itself. In this case, seeing the court is not a call to action to purchase the expensive sportswear; the brand is seen through its proximity to cool. In branding leisure spaces, the sell is much more subliminal—and spreadable. Jenny Xie of Curbed writes that the basketball court as space is “ripe for mesmerizing transformations that challenge our sense of the familiar,” as she describes the trend of painting basketball courts around the world.

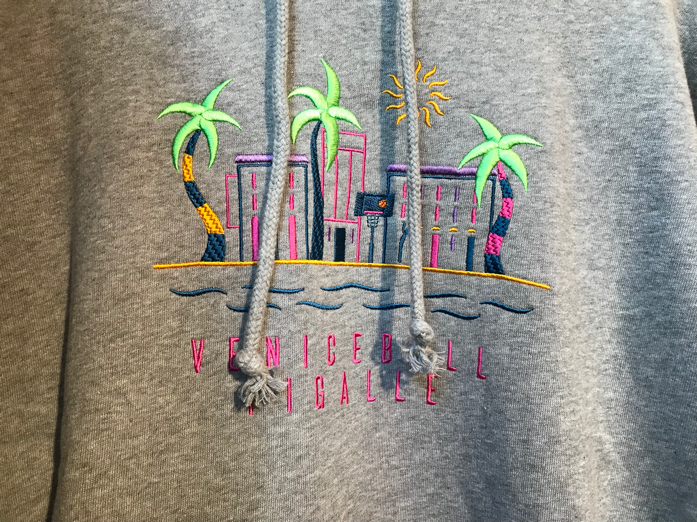

Basketball is an American export molded by Black culture, expanded by global capitalism, and transformed into a complicated site of consumption—of bodies, of space, and of technology. As I enter the Pigalle Basketball shop, I realize another aspect of Harvey’s time-space compression—the flattening of spatial specificity. In this case, I see sweatshirts and keychains in the technicolor Pigalle flair but with a distinct difference—the word VeniceBall scrawled underneath a logo comprised of palm trees and beachfront property. As a tourist in Paris, I’m struck by seeing the Southern California image of the adjacent neighborhood to my own. For many, Venice, California represents another site of important basketball courts. Linked to films such as White Men Can’t Jump (1992) and Lords of Dogtown (2005), Venice is a mythic outdoor sporting space associated with a particular form of authenticity which Pigalle is seemingly tapping into with this collaboration. It is also an area grappling with the effects of gentrification, often referred to as “Silicon Beach,” as Google, Snapchat and Facebook set up shop down the street from the iconic courts.

To me, this reflects Pigalle Basketball as a “transnational zone,” a term Julian Murphet uses to refer to retail spaces “as much about the experience of ‘non-place’ as they are about consumption.” [4] NBA jerseys of French players are next to the league’s American superstars. Looking out through the storefront, a Chicago Bulls mini basketball backboard is affixed to the front door. Pigalle, clearly labeled by its neighborhood, is linked to larger transnational sporting goods and sportswear corporations, whether in their collaboration with Nike or the VeniceBall basketball leagues.

The Pigalle team describe their vision as aiming to “establish visual parallels between the past, present and future of modernism from the ‘avant garde’ era of the beginning of the 20th century, to the ‘open source’ times we live in today, and our interpretation of the future aesthetics of basketball and sport in general.” As its visitors traverse time and space each time they step onto the court or into the shop, they are consumers of Pigalle and Paris (perhaps), Venice and viral marketing (of course). But most importantly, they are creators—postmodern producers who transmit in rapid turnover time in a transnational zone created to capitalize on the cool of one of the most popular sports in the world.

Image Credits:

1. Teenagers playing a pickup game of basketball at Pigalle court in Paris, France. (author’s personal collection)

2. A patron enters the Pigalle Basketball shop across the street from the court. (author’s personal collection)

3. The author falls victim to the “Instagrammability” of the space. (author’s personal collection)

4. The collaboration between VeniceBall and Pigalle represents the glocal marketability of these outdoor sporting spaces. (author’s personal collection)

5. A view from inside of the Pigalle Basketball shop. (author’s personal collection)

6. Bright blue gates replace the structures which once obscured the Pigalle court from view. (author’s personal collection)

Please feel free to comment.

- David Harvey, The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change (Hoboken: Wiley, 1992), 285. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Ibid., 288. [↩]

- Julian Murphet, “Postmodernism and Space,” in The Cambridge Companion to Postmodernism, ed. Steven Connor (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 120. [↩]

For many, Venice, California represents another site of important basketball courts…

Good one