Transnational Television Dramas and the Aesthetics of Conspicuous Localism

Tim Havens / University of Iowa

This semester, graduate students in my seminar and I started a Global Television Club, where we screen pilot episodes of television series from around the world. Specifically, we selected recent, high-end drama series co-produced and released (more or less) simultaneously in multiple territories. Our goal was more than entertainment or familiarity with non-U.S. television cultures: instead, we sought to identify common stylistic, thematic, and generic tendencies that might cut across these transnational television dramas, regardless of country-of-origin. Unfortunately, due to scheduling problems, our investigation didn’t get far, and we are planning on continuing our investigation in the fall. Still, I include several of the observations that emerged out of the club’s viewings and discussions below.

Within the global television industries, little doubt exists that high-end transnational television drama is a new and growing phenomenon, enabled by the streaming ambitions of FAANG (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, and Google), as well as several dozen smaller streaming companies from around the world, including the BBC, Arte in France, ZDF in Germany, and iQiyi in China, to name only a few. In 2017, C21 Media, one of the leading international television trade magazines, published a report assessing the trend and examining its impact of television drama production in numerous markets worldwide.

In television studies, we have been hesitant to identify this new trend, perhaps because of the contentious status of the concept of “quality” in a field based on the idea that all forms of culture expression can be inherently valuable, and that the designation of “quality” or “artistic” acumen are mere discourses of classed, gendered, and raced social distinctions. I largely sympathize with this perspective; I find the critiques of quality in television programming that folks like Elana Levine and Michael Z. Newman’s make in Legitimating Television—that many of the features of supposedly high-quality television dramas are dismissed or ignored when they appear in women’s genres—quite convincing. Nevertheless, I do believe that we are seeing the emergence of new, transnational discourse of quality television within the programming industries—what I would call a certain form of “industry lore”—that, together with the technological and economic structures of the global media industries, are ushering in an era of high-budget transnational television series. It is this trend that I want to analyze here, while bracketing for the moment questions of quality or art.

Co-produced transnational television dramas, released in multiple territories, are certainly nothing new. They have frequently featured a limited number of genres, particularly historical miniseries with characters and stories that resonate across national borders. In Europe in the 1980s, this strategy was deployed in order to leverage production budgets from multiple territories and compete with high-end, imported U.S. television programs. While this specific model of co-production led to derisive comments about culturally vacuous “Europudding” miniseries, it is also the case that a number of well-received and popular series emerged from this model.

Much the same economic and cultural logic is at work in the surge in today’s transnational television dramas as well, but several features of the current moment in transnational television drama are unique as well, most obviously the budgets. Babylon Berlin, co-produced by Sky and ARD for simultaneous streaming release in the UK and Germany, is the most non-English series ever produced. Occupied, a Norwegian political thrilled co-produced by Arte and simultaneously released in France is the most expensive Norwegian show ever. Likewise for the Korean series Descendants of the Sun, co-produced and simultaneously released by Chinese streaming service iQiyi. And so on.

The global streaming wars between Amazon and Netflix drive these budgets: this year, Netflix will put about $8 billion into original programming worldwide, as will Amazon, while HBO, Hulu, and Sky are pumping in hundreds of millions of dollars each. In addition, there are hundreds of medium sized streaming services around the world that are pouring in money as well.

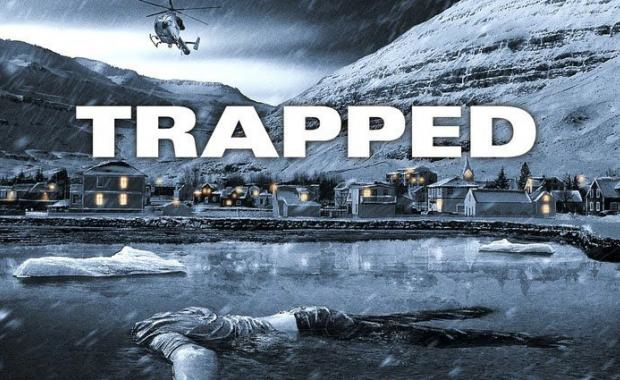

All of this production money leads to a second significantly different feature on contemporary transnational television drama, what I would call “conspicuous localism.” A major part of the expense of these series comes from the variety of locations in which they are shot and the extensive use of HD cinematography to create a strong sense of place, unlike most co-productions in television’s past. The Icelandic series Trapped, co-produced with German broadcaster ZDF, features cascading shots of massive, snowy mountains; the Japanese series Hibana: Spark opens with a craning shot of pedestrian mall in Osaka with green mountains in the distance, and much of the subsequent action takes place in the Kichijoji and nearby Kami Shakuji areas of Tokyo. This conspicuous localism is further reinforced by local-language production, even to the point of shooting in subnational dialects (witness the Belgian Arte co-production in Flemish, Hotel Beau Séjour), as well as plotlines and themes that often require very specific cultural knowledge, such as the Japanese two-team stand-up comedic form, manzai, which is at the heart of the story in Hibana: Spark.

This sense of conspicuous localism is for me the most interesting cultural trend in transnational television drama today. I call it “conspicuous,” riffing on the idea “conspicuous consumption,” because I believe that this form of localism serves quite specific audience and industry needs that are all about appealing to others, much as conspicuous consumption is done to signal to others. The conspicuous localism of the cinematography, storylines, and languages of contemporary transnational television drama are, I believe designed to appeal to a cosmopolitan international audience. For subscribers to streaming platforms, dramas with a strong sense of authenticity offer cosmopolitan cultural capital to affluent viewers in a way that less conspicuously local production strategies do. Given the nationalist and ethnic backlashes against globalization and immigration in many Western nations, the consumption of seemingly authentic media culture from abroad is a way to signal to one’ self and others one’s cosmopolitanism.

Meanwhile, for creative industries around the world, conspicuous localism is a way to promote local tourism, as well as to spotlight and expand local creative industries. For the nation-of-origin, high-end television dramas serve nationalist ends that are similar to the opera houses of the 19th and 20th centuries. Much as opera houses and locally-produced operas in the national language became markers of a nation’s modernity in earlier centuries, so are transnational television dramas markers of the maturity of a nation’s creative industries in the 21st century.

Image Credits:

1. Hibana: Spark

2. Trapped

3. Descendants of the Sun

4. Hotel Beau Séjour

5. Babylon Berlin

Please feel free to comment.

I like the term “conspicuous localism”. It’s a term that I wish I would’ve come across before presenting on a similar topic about “Japaneseness” in exported Japanese-produced tv shows. My argument was that networks such as Fuji TV are now consciously choosing to produce shows that will appeal to/avoid alienating international audiences. Although they purport to be faithfully representing the nation of Japan to the rest of the world through locally-produced tv programs, they are playing into the idea of what they believe the rest of the world thinks is “Japanese.” There are certainly ulterior motives; to use localism to promote tourism and bring greater attention to the production companies, though its not spoken about in these terms. With the prevalence and dominance of streaming as a means of international distribution, these shows are more consciously produced and used as cultural commodities to be exported to as many markets as possible.

The article wisely indicates the term of “conspicuous localism” as a new tendency of the new millennium which as I interpret is a strategy of the television studios and streaming services to reach multiple territories and appeal transnational audiences. The author selects the Japanese series Hibana:Spark which is produced by Netflix as the demonstration of this effort, which makes me think of Netflix’s other co-produced TV series in the recent couple of years because I am following one of the anime, Devilman: Crybaby that Netflix distributed in 2018. After doing some research, I find that Netflix has launched several plans about Japanese anime, they expect to produce 30 anime in 2018. Some critics assume this move will alter the blueprint of the Japanese animation circle. I consider the intension behind this scheme is a strategy of “conspicuous localism”, as the author suggest here, to improve transnational viewership and they want to target the niche audience which are minor group of people in America that immersed themselves in the cult subculture of anime. Meanwhile, they can develop a new taste to this subculture to those who are not familiar to this form.

Interesting article

play papa game to learn cooking and time management it is one of the outstanding game here you also know to utilizing the time between cooking this is really an amazing game you play Papa cupcakeria game online for better experience this is a fantastic game

Do you have a list or website of all the different series you have seen?

Interesting yet I wonder how the audiences comprehend the sense of “transnationalism” and “localism” within these co-produced programs.