Stop Teaching Software, Start Teaching Software Literacy

Katherine Morrissey / Rochester Institute of Technology

I’ve officially stopped teaching software. I’m done. No more software driven lessons. No more step-by-step tutorials. No more hovering over my students in a lab. Here’s why you should stop too.

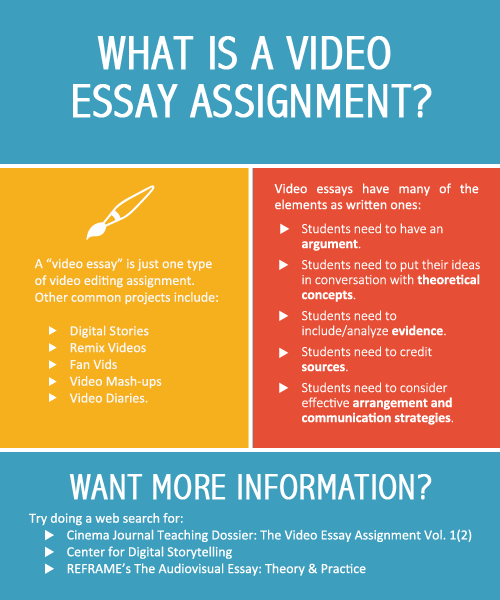

There are many different kinds of digital projects out there: essays rendered as websites, class wikis and blogs, digital art, remix videos, imagined iPhone apps, the list goes on and on. I will use a video essay project as my primary example. [1]

One: You thought you knew iMovie, but a new version came out last week.

Every piece of software your students need is being overhauled on an annual basis. Some of that software works on a Mac, some of it on a PC. (I have no idea what works on Linux, but that’s important too.) If you reserve a campus computer lab—assuming you’re lucky enough to have access to one—it could be a Mac lab with the latest version of iMovie. Or, it may only offer Adobe Premiere circa 2010. If it’s a PC lab, maybe Movie Maker is installed. Or (more likely), you’ll need to make arrangements with the lab to install it for your class. (This will result in all the students who don’t use Windows looking horrified and feeling deeply confused. But, of course, all the Windows users will have the same experience if you choose the Mac lab.) Then, what about the time students need to spend working on projects outside of class? What good will a lab-session do them when they sit down in front of the technology they use every day?

Amidst all the software choices and limitations, will instructing students in one particular piece of software really help them complete their work and prepare for future digital assignments? I’m not convinced it can. Yes, you might require a cloud-based tool like WeVideo (cheap, browser-based, good for beginners, $0-14 monthly) or Adobe Premiere CC (steeper learning curve, more features, $19 – $49 monthly). However, there are numerous reasons why one of these programs will work for some of your students and another will not. (And, are you really okay with locking your students into a subscription service? Adobe Creative Cloud subscriptions can cost $239 – $499 annually.)

Two: Some of your students know more about video editing than you do. (And some of them don’t know anything at all.)

Here are some of the video editing programs my students used last semester: MovieMaker, iMovie, Adobe Premiere, Open Broadcast Software, AfterEffects, Sony Vegas, Open Shot Video Editor, Final Cut Pro, and WeVideo. Some students were using software for the first time; many of the students were not. Some students want free software that is easy to learn. Others will already have Adobe Creative Cloud subscriptions. Some of your students only own tablets. The point is, individual students have their own technology needs and preferences.

And why shouldn’t they? Why should we shepherd our students into computer labs each semester and push them to learn software simply because it happens to be a) the one we have access to in a particular lab, or, b) the one program we know how to use. Our students come to our classrooms with a wide array of skill sets and skill gaps. Rather than constraining their efforts by teaching one program, it is far more important to teach them essential skills: The basic techniques that they will use again and again, regardless of whatever piece of software they are using at the moment. By teaching key project components and helping student work with software on their own, we model essential media literacy skills: Adaptability, flexibility, and comfort with the unfamiliar.

Our class time is precious. We cannot spend this time telling students which buttons to click and when. Instead, we need to teach students to feel confident approaching new programs and comfortable learning as they go. Over the course of their adult lives, our students will need to adapt to an endless array of upgrades, version changes, and technology setups. These are the new norms for today’s digital practitioners.

Three: Sometimes you still need to teach software.

In recommending that we spend less time teaching software, I am not advocating that everyone immediately stop teaching software. There are numerous courses and degree programs where students need extensive exposure to the specific software, programming languages, and procedures favored by a particular professional field. You will also have students who need intensive help with the software they’ve chosen for a project. These students are not best served by going through the steps en masse. In the process of creating a digital project, many individual glitches and errors can occur. These circumstances nearly always require individualized troubleshooting. You will be your students’ main contact when issues arise. Be ready to meet with students, sit with them next to their computers, and to try different things. Be aware of your limits and know when you need to ask for help from your school Help Desk or Tech Support.

Instead of asking you to give up teaching software, I challenge you to consider why, in your particular class context, you are teaching a specific type of software. If you are teaching software simply because it’s the one you know best or the one the lab happens to have installed, this may not be the best use of your class time. More importantly, you might be doing students a disservice. Think about the time you can repurpose if you shift away from guiding students step by step through a program. Think about the time you are creating for peer feedback and project revisions.

Four: Digital projects are a lesson in time management.

We are all familiar with the process of writing an essay. The steps are so routine we often don’t consider the effort it takes to move from idea to final draft. Digital projects are new and unfamiliar. The steps they require vary from class to class and from one assignment to another. To develop effective pedagogies, and to help students produce strong projects, we need to focus on process.

I am still figuring out the most effective ways to teach media literacy skills rather than software. Over time, however, three core elements are emerging in my own pedagogy: 1) Scaffolding: Isolating the steps/skills needed and taking them one at a time. 2) Normalization and Collaboration: Making students aware of common struggles and alternative approaches. 3) Project planning and work time: Asking students to produce timelines, identify obstacles, and set aside time to work and get help.

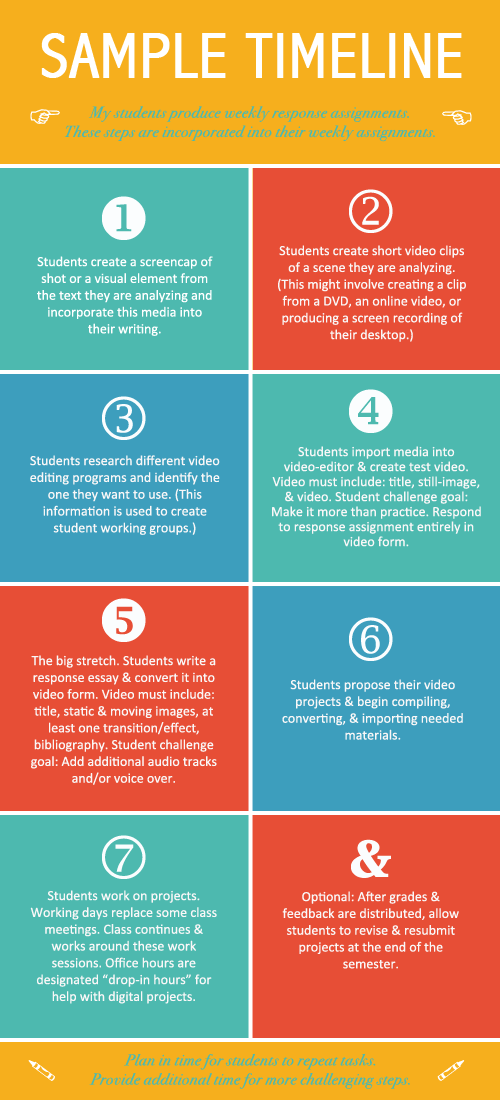

Digital projects can be broken down into a series of essential steps and necessary skills. When my students make a video essay they need to know: how to make a screencap; how to make a video/audio clip; how to import images, video, and sound into an editing program; how to work with an editor’s timeline and access various features/tools. These steps can be broken down into individual assignments, all of them building up to the project deadline. Once students learn the essentials, begin complicating their assignments. Students can teach themselves as they go, building up their skills and preparing for the final project.

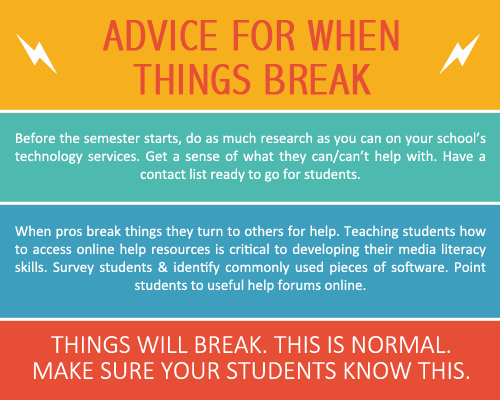

Students cannot do this work alone. Adapting to new software requires we be comfortable asking for help. Teaching students that their struggles are normal, how to get help, and how to find useful resources, are essential components for developing their media literacy skills.

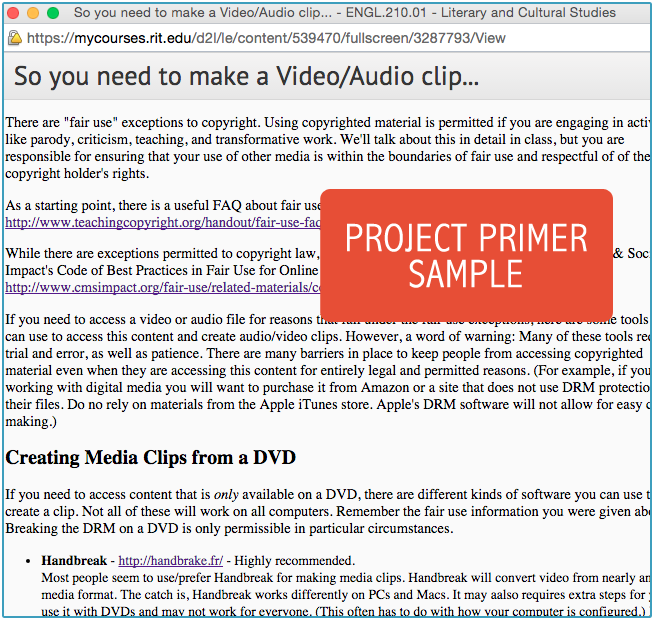

Each semester, with my students’ assistance, I add to and refine a set of project primers. The primers are kept online and available to students 24/7. Each step or mini-assignment my students take on comes with a list of tips, software options, and general resources. Based on the software students choose, they are placed in small working groups. Working groups allow students to co-learn, assisting each other as they go. After each assignment we discuss what went wrong and what steps students took to address problems. I want my students to learn that importing and conversion errors aren’t a sign that they are failing, but are, instead, are normal part of the process.

Finally, students need help with time management and they need time to work. Digital projects are not papers. It is nearly impossible to accomplish them by drinking a lot of coffee and pulling an all-nighter. Students need time to gather materials, deal with errors, and refine their analysis. They also need time to focus and work. The problem is, class time in a computer lab will not be useful to every student. Instead of packing into a single lab together, I schedule working days. Some students bring laptops and work together in the classroom, some groups go to a computer lab that’s been reserved, others work from home. No one gets credit unless they check in and provide a daily to-do list when class starts. When class finishes, they check out by reporting what they’ve done, listing anything they are having problems with, and how they plan to get help. Work days are also effective for the many times when I do not have access to a lab. There are many different ways for work to happen, the important thing is that everyone is working somewhere.

Every situation is different. These steps are will not be effective for every teacher and teaching context. However, there is much to be gained by struggling through as a group, asking for help when needed, and witnessing other people’s work practices. I encourage other teachers to take the risk. Leave your software comfort zones! By working with your students there is much to learn about software, digital genres, and pedagogy. The only way to do this is to cultivate an environment where the students are teaching themselves as much as you are teaching them.

Image Credits:

1. Computer Lab.

2. Video Essay Assignment (author’s image)

3. When Things Break (author’s image)

4. Sample Timeline (author’s image)

5. Project primers (author’s screen grab)

Please feel free to comment.

- For further information on the video essay assignment, see: “The Video Essay Assignment, Cinema Journal Teaching Dossier Vol. 1(2)”; the Center for Digital Storytelling; and The Audiovisual Essay [↩]

Thank you for an informative post. It really helps a lot! Keep the good ones coming in.

very helpful and informative. Many thanks

Much thanks to you for an educational post. It truly helps a considerable measure! Keep the great ones coming in.

We have got such a software here.

KineMaster is a full-featured video editor for Android. KineMaster has powerful tools that are easy to use, like multiple video layers, blending modes, voiceovers, chroma-key, speed control, transitions, subtitles, special effects, and so much more

There are many different ways for work to happen, the important thing is that everyone is working somewhere. It truly helps a considerable measure! Keep the great ones coming in.KineMaster has powerful tools that are easy to use, like multiple video layers, blending modes, voiceovers, chroma-key.

I live in Europe. Thanks for this. I never understood how even 1% of people could vote for Trump. Seems that angry and desperate people felt they were finally being listened to, by the man with the gold plated toilets.