Stasis, Change, and Televisual Comic Book Film Franchising

Derek Johnson / University of Wisconsin-Madison

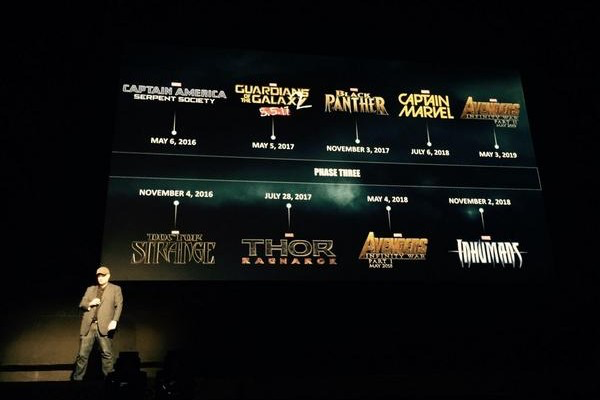

Of greatest concern to Harris about the film industry of 2014 is the way that it replicated itself into 2015 and beyond, as made most tangibly clear by the carefully planned futures of the DC Comics and Marvel Comics film franchises. Each company made spectacular announcements throughout the year revealing the titles of dozens of comic book films to be produced by the end of the decade. As Harris writes, the film industry of 2014 is all about “creating a sense of anticipation in its target audience that is so heightened, so nurtured, and so constant that moviegoers are effectively distracted from how infrequently their expectations are actually satisfied. Movies are no longer about the thing; they’re about the next thing, the tease, the Easter egg, the post-credit sequence, the promise of a future at which the moment we’re in can only hint.” Despite his doom and gloom, Harris provides here an extremely useful perspective on narrative aesthetics in contemporary media franchising. Much as I have argued that media franchising applies the logic of episodic production long central to US television to a host of other entertainment industries, Harris conceptualizes this promise and anticipation of the future as a televisionification of blockbuster film. “TV knows how to keep people coming back, which is its job, every day and every week, and is a quality that, above all others, the people who finance movies would dearly love to poach,” Harris writes. While the specific episodic logics that have long been a part of comic book form can be seen to have their own transformational effects on television (as argued by Alisa Perren), Harris’ insight encourages us to look in parallel to television studies to understand what is happening in the industrial embrace of the comic book film.

Harris’ essay seems to focus only on stasis. He looks at the production slate for Marvel Studios and sees the extension of a 2014 formula (itself an extension of what’s proven successful in years past) to the next several years of blockbuster filmmaking through 2020. He sees the replication of that formula as a reason to be concerned for all “the movies that aren’t getting made.” And he’s right. The Marvel films are nothing if not formulaic, and the crowding of the blockbuster market by comic book films like here https://grademiners.com/dissertation-chapters —to say nothing of what blockbuster emphasis in general means for quieter independent projects and untested ideas—is a concern about diversity of voice and perspective that cannot be waved away by a conversation about the art of repetition. But Harris’ invocation of television means we have to think about the unique integers demanded by repetition too.

produced, the odds are that one or two “good” movies will “sprout up.” Instead of looking at such instances as anomalies in an otherwise homogeneous sea of carefully managed production, though, we might think about them as important parts of franchising logic—the variance and “unique integers” necessary to keep the formula fresh and, especially, to adapt that formula to new audiences and tastes. More than anything, Harris seems troubled by the “Stalinist” way studios have planned out the road to 2020, introducing one new comic book hero or property after another to be run through the same blockbuster franchise formula. For DC, Superman vs. Batman will lead to Suicide Squad and Wonder Woman; for Marvel, Avengers: Age of Ultron will lead to Ant-Man and Captain Marvel. Yet there’s something permitted here in the plugging of all these different integers into the same formula that earlier moments in the franchising of comic book films did not. The promise of a future represented by Grademiners.com these extended production slates depends on a commitment to gradual, cumulative narrative change and the exploration of new characters to replace the old (no more rebooting in order to tell the exact same story again, a la Sony’s Spider-Man film franchise; though the breaking news that Sony will allow Marvel to reunite Spider-Man and The Avengers suggests one last reboot may be required there before Marvel commits to integrating the character in their long-term, future-thinking strategy). That promise of cumulative development may ultimately go undelivered, but it imagines Hollywood franchise filmmaking as something ideally balancing formulaic stasis with iterative dynamism.

Image Credits:

1. The “televisualization” of the comic book film.

2. The Marvel film slate through 2018 is announced.

3. The DC Comics film release line-up through 2020.

4. Carol Danvers, also known as Captain Marvel, is set to make her big-screen debut in 2018.

5. A publicity still for Wonder Woman, directed by Michelle MacLaren and slated for a 2017 release.

Please feel free to comment.

- Jeffrey Sconce, “What If: Charting Television’s New Textual Boundaries.” Television After TV: Essays on a Medium in Transition (eds. Lynn Spiegel and Jan Olsson, pp. 93-112. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004), 105. [↩]

hey good one