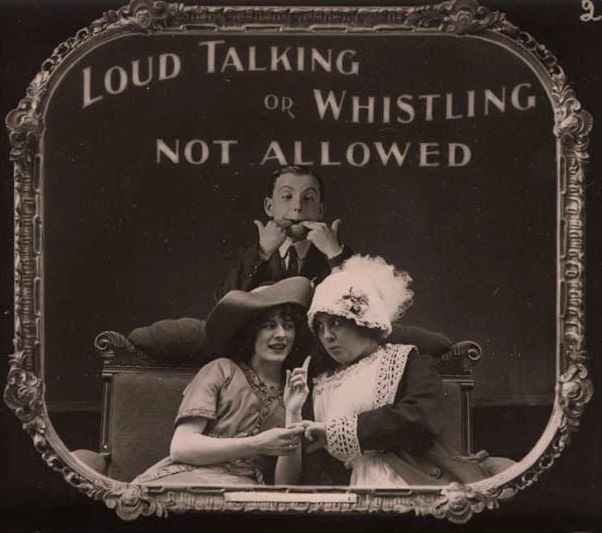

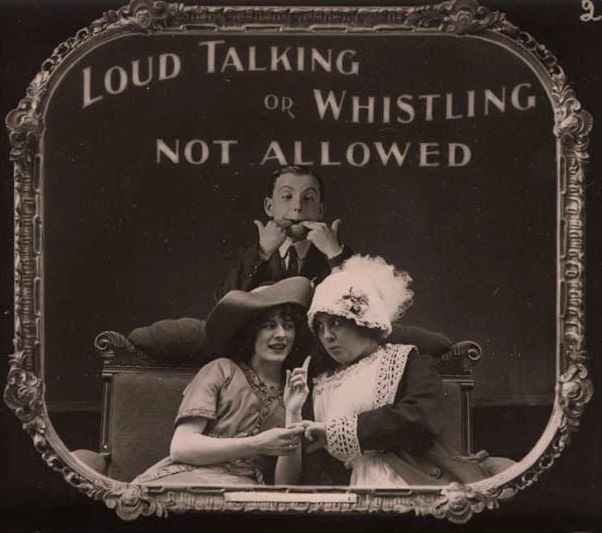

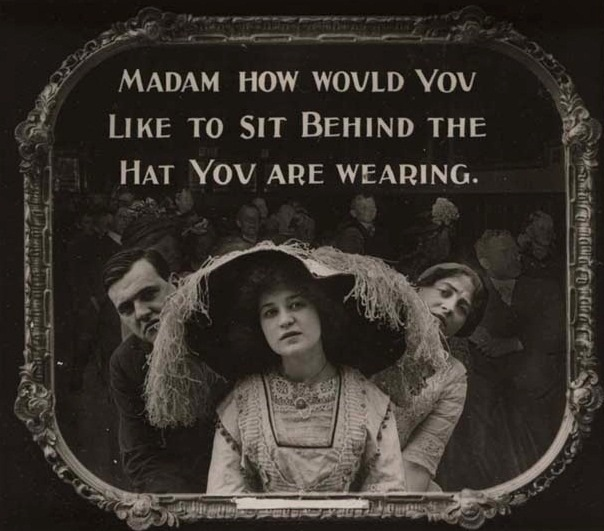

Silent-era pre-show projector slide warning viewers against disruptive behavior.

Silent-era pre-show projector slide warning viewers against disruptive behavior.Among the voluminous critical commentary produced over the decades on the social experience of moviegoing, one of the most recurrent strains concerns the public comportment of one’s fellow patrons. For a medium whose culturally dominant forms have, after all, privileged the spectator’s immersion in self-contained narrative worlds, the ever-present possibility remains that less disciplined or overtly disruptive ticketholders will effectively become an unexpected (and unrewarding) part of the show. Still, this common criticism of moviegoers (always others, never oneself) has now perhaps become less to do with patrons’ actual behavior than with the relative exceptionality of going to a public movie theater in an era saturated with home viewing options. If, as Charles Acland’s research has shown, avid moviegoers (i.e., those attending more than one movie every two weeks) now account for only about 8 percent of the U.S. population but make up 75 percent of a film’s ticket buyers to

write my essay for me during its first two weeks in theaters, then instances of misbehavior might be all the more likely to stick in the memories of that far larger demographic which treats theatrical attendance as a special occasion.

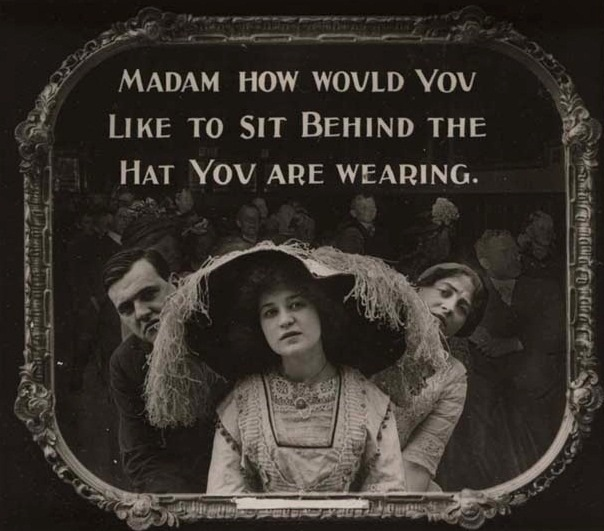

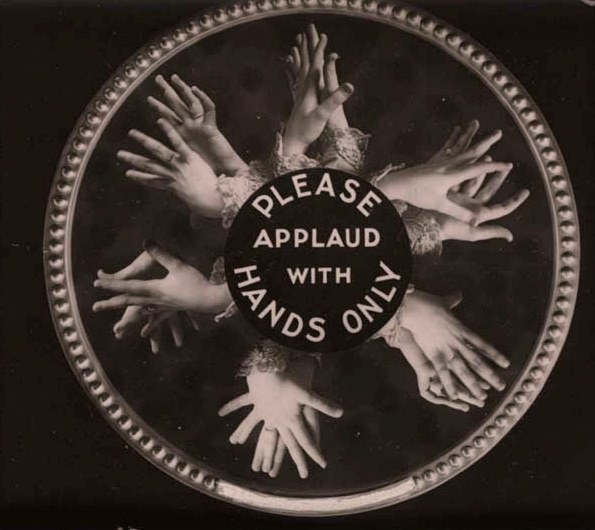

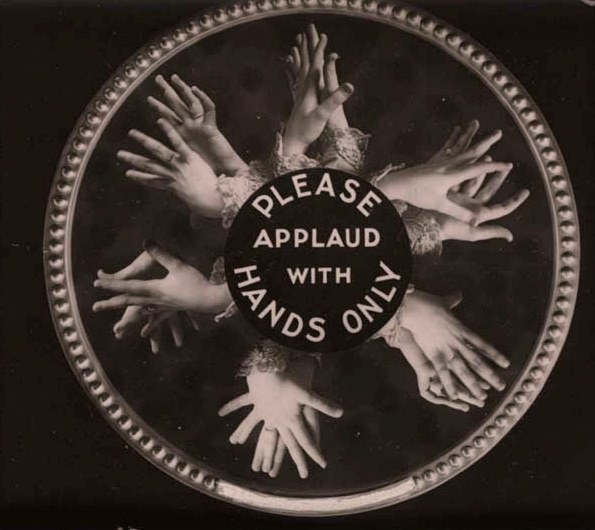

Further examples of silent-era pre-show projector slides.

Further examples of silent-era pre-show projector slides.In cinema’s silent years, undisciplined comportment derived from over-sized hats, smoking, whistling, foot stomping, and so on—as the pre-show projector slides shown above imply. In our present moment,

common complaints have coalesced around the intrusion of external technology—especially cell phone use—into a cinematic apparatus which, for all its vaunted digital transitions, still basically retains its century-old relationship between a projector and a single screen. Meanwhile, notable exceptions to these expectations have become framed as special events (and accordingly sold at premium ticket prices), even if they more closely resemble the quotidian pleasures of home viewing: from Disney’s experimentation with “second screen” events where patrons play games and access expanded content on an iPad app while watching the film, to

Hecklevision screenings in which viewers use the MuVChat app to text snarky comments that appear onscreen during a “bad” movie (à la

Mystery Science Theater 3000).

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tYpRQ5Mw2lM#t=71[/youtube]

Promotional trailer for Disney’s 2013 “Second Screen Live” screenings of The Little Mermaid (1989)As might be expected, complaints about audience behavior primarily center around the corporately owned multiplex—that most populist of theatrical sites, where ostensibly broad tastes and broad viewerships come together under the same blandly interchangeable roofs. Anyone who has been to a multiplex in the last ten years has, of course, seen the pre-roll promos warning patrons to silence their cell phones and refrain from talking or texting, although certain chains enforce these rules of decorum with more verve than others. The Alamo Drafthouse Cinema chain has, for example, manifestly promoted its anti-texting policies as a means of differentiating itself from larger corporate chains like AMC and Regal, a practice complementing its selective programming of cult cinema and special screenings geared toward film aficionados who can exhibit “proper” modes of aesthetic appreciation. Take the 2011 voicemail from an angry Drafthouse ejectee, since repurposed in one of the chain’s anti-texting promos:

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1L3eeC2lJZs[/youtube]

Alamo Drafthouse Cinema anti-texting promoAs the misogynistic tenor of so many YouTube comments (e.g., “dumb girl,” “stupid bitch”) on this video suggest, however, calls for better theater etiquette can easily shade into a thinly veiled demonization of mass (multiplex) culture and its audiences as “feminized” philistines. Likewise, when a retired police captain

shot an unarmed man in a dispute over texting at a Florida multiplex in January 2014, many online commenters reacted to the news coverage as a cautionary tale or even a violent wish-fulfillment fantasy about the consequences of theater misconduct. And yet, between the twin poles of second-screen events aimed at entertaining antsy kids/millennials and theater franchises that make a virtue of aggressive “shushing,” there are a wide variety of disruptive behaviors existing beyond the multiplex.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hKBiLCJNBS4[/youtube]

Surveillance footage of fatal shooting at Cobb Grove 16 multiplex, Wesley Chapel, Florida, on January 13, 2014Indeed, the persistently elitist assumption that multiplex patrons are the worst behaved moviegoers belies the fact that audiences at art houses and repertory theaters are as likely—or even more likely—to be disruptive (albeit in sometimes different ways). Surely readers who have spent their fair share of time in arthouse theaters will have their own personal batch of horror stories about eccentric, unsettling, or otherwise unconventional characters or behavior rivaling that of any multiplex show: inappropriate or bizarre outbursts, idiosyncratic seating rituals, odd comings-and-goings, smuggled-in meals, and other breaches of decorum. There are, of course, plenty of historical precedents for unconventional arthouse behavior at

https://grademiners.com/dissertation-help —such as the origin stories for cult films like

Casablanca (1942) and

The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), in which rep theater viewers developed viewing rituals to perform along with the film out of (respectively) earnest appreciation or ironic deprecation—but such cult activities are presumed to

enhance the overall moviegoing experience, not detract from it.

Lucas Hilderbrand observes that bootleg recordings of movies captured at multiplex theaters often reveal the sheer range of ambient sights and sounds (e.g., glowing exit signs, quiet verbalizations, eating noises, people occasionally coming and going) that the average viewer is generally accustomed to tune out. But what of less disciplined behavior in the arthouse experience? The most obvious explanation might be that such misbehavior is simply more noticeable if the films shown in art houses tend to be more challenging in form and content, ostensibly requiring more focused contemplation than the average Hollywood picture—but that argument would certainly not apply to all films programmed at either specialty theaters or multiplexes (especially around awards season).

Another consideration is the question of which types of people are more likely to attend art houses than multiplexes, particularly as expressions of cultural distinction. A recent study has found that people tend to ascribe higher value and more “authenticity” to an artwork if the artist him/herself is perceived as eccentric , but we might ponder whether the reverse is true: are more eccentric people more likely essay writing service to gravitate toward “higher” art forms and the exhibition spaces associated therewith? In other words, do the same taste biases that would associate art houses with a “higher” or more “refined” class of cinema also encourage a “stranger” clientele—or perhaps at least a demographic more oblivious to its own potential for disruptiveness? If texting in the multiplex seems to scream self-absorbed entitlement, what of the arthouse aficionado’s distracting or eccentric comportment, cloaked beneath the aesthete’s self-satisfaction of simply being in an independent theater watching artsier fare?

For an example of an extreme case, see Angela Christlieb and Stephen Kijak’s documentary Cinemania (2002), which follows a cadre of New Yorkers with an obsessive-compulsive drive to attend hundreds of movies per month at the city’s repertory houses. Most of them are unemployed, living off disability benefits, and it is not difficult to see their cinephilia as potential expressions of underlying personality disorders.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xU3akDbqJsc[/youtube]

The cinephile as sociopath? (from Cinemania DVD bonus features)Extreme cases though they may be, such patrons nevertheless suggest that aesthetic preferences toward theaters showing less conventional cinematic fare may be inevitably accompanied by encounters with less conventional viewers than found at the multiplex. Tobin Siebers argues that “modern art’s love affair with misshapen and twisted bodies, stunning variety of human forms, intense representation of traumatic injury and psychological alienation, and underlying preoccupation with wounds and tormented flesh” reveals the centrality of disability and other forms of human variation to judgments of aesthetic worth. Yet, if mental or physical difference is so often aestheticized

within modern art, “[t]he ability of the work of art to take possession of an audience…is almost always treated as serving a call to knowledge or greater self-possession, and those who are possessed by more powerful experiences are thought to be mentally defective.” As easy as it might be to dismiss art houses’ more disruptive attendees as “kooks” or “weirdoes,” we might do well to consider them an added price of admission to cinematic art forms that already fall outside the cultural or economic norm. After all, if a taste for experiential diversity likely draws us to such theaters in the first place, then what does reviling this human diversity lurking just outside the screen truly accomplish?

Image Credits:

1. Pre-projector slide

2. Pre-projector slide

3. Pre-projector slide

Please feel free to comment.