Technologies of Ability: Media in Academia

Elizabeth Ellcessor / Indiana University

Warm up the projector, queue the clip, turn up the volume, and dim the lights. This routine is no doubt familiar to many of us, as we prepare to show a film, a short clip, or other media in our classrooms, at a conference, or in other presentations. It is not, however, without its challenges.

The wireless internet is patchy, and the clip doesn’t load. The projector bulb is burned out, with no means to quickly replace it. Your university has scrapped all of the VCRs. For some reason there’s no volume. Any of these, or similar, mishaps can derail a presentation for all involved.

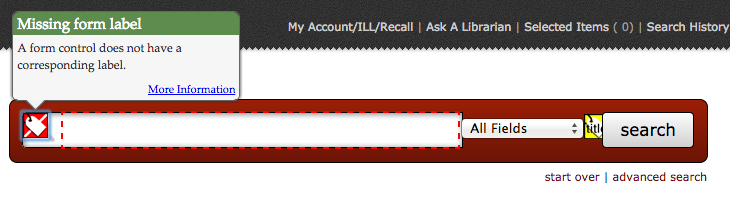

The failure of such presentational media technology has been described as the “slightly hilarious” curse of the new media scholar, who depends upon digital tools to conduct and share scholarship.1 And the curse is spreading. Within increasingly digitized classroom spaces, and in online course contexts, we all become subject to the whims of technological systems, making choices and creating workarounds to accommodate what our tools will and will not do at a given moment. Students, similarly, experience the failure of new media performance, as online forms refuse to submit, videos do not load, and readings that we know were posted are suddenly inaccessible; the volume of screenshots documenting such failures speaks to students’ growing familiarity with such failures.

The very commonplace nature of such failures, or glitches, ought to indicate that the functional media, presentational tools, and classroom technologies that surround us are neither transparent nor free of embedded values and expectations. Yet, as Peter Krapp has argued, “our digital media culture is predicated on communication efficiencies to an extent that can obscure or veil the sources of noise as faults, glitches, and bugs are too often relegated to the realm of the accidental.”2 In fact, these inefficiencies are constitutive of digital media technologies and their operations, leading Krapp to call for the study of digital media culture from the perspective of these pervasive misfires.

This corrective is necessary because of the grand narrative of digital media as a march toward ever better, smaller, more reliable, and more pervasive technologies integrated seamlessly with our needs and uses. Such a narrative is as strong, if not stronger, in the context of presentational or educational technologies. This was the claim made by educational radio,3 by Channel One and Sesame Street, and it is the claim most recently made by purveyors of massively open online courses.4 When one states that a given media or technology will “revolutionize” education, one partakes in this narrative, which is, at heart, an ideology of ability.

By calling this an “ideology of ability,” I want to indicate that this discourse presumes that media technology will function seamlessly, will enable its users to do particular things, and will ultimately improve the state of education. No matter the evidence to the contrary, as seen in countless glitches, miscommunications, or failures, these precepts remain in place. Under an ideology of ability, classroom media are both valorized and made invisible in their functioning. The media, and the pedagogical activities that rely upon them, are furthermore technologies of ability, in the Foucauldian sense. They assume and enforce a normative set of bodily abilities as prerequisites for learning, and their growing imbrication in standard forms of pedagogy and academic communication only cements their power to exclude those who may not embody these normative bodyminds.5

To begin from the point of failure, from the inefficiencies, from the exclusions means that it is particularly fruitful to consider the use of presentational and educational media within film and media studies from the standpoint of disability. Several cases of digital media inaccessibility have risen to national attention in recent years, most notably the injunction against campus use of e-readers that did not have controls that could be navigated non-visually. Yet, at a more mundane level, standard presentational and educational media technologies exclude students with disabilities on a daily basis. The ideology of ability evident in these media technologies reinforces a broader cultural ableism that casts disability as an individual deficit to be solved privately (rather than as a social problem requiring collective solutions).6

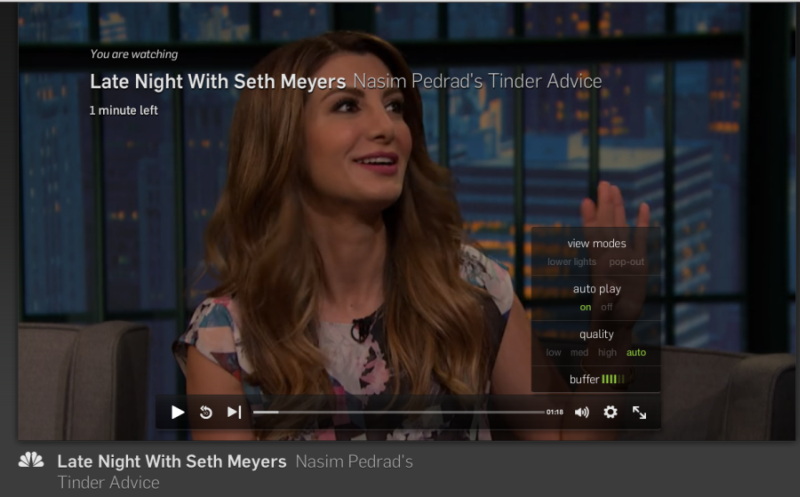

For example, our omnipresent media clips may not be captioned (for d/Deaf or hard of hearing students) or audio-described (for visually impaired students). In some cases, this is a failure of technology–these features may not be available. In other cases, it is an enactment of instructor privilege, assuming these features to be unnecessary to a class presumed to be able. Yet, there is no simple solution. Clips that are not captioned require instructors to find campus services to help, or to learn how to caption clips themselves (a time- and labor-intensive process). Campus services may offer to make clips accessible for students with disabilities, but often do so via private, streaming services that the student must access from their own computer on their own time. Though this provides accommodation, it is, in the words of one closed-captioning professional, “not the same experience” as the shared viewing of a traditional media screening or in-class clip.

There have been some indications that, “with the growth of online education, it is now largely the obligation of the instructors themselves to proactively design courses that are equally accessible to all students.”7 Such a stance drastically increases the scope and quantity of instructors’ labor, particularly as course management systems are often purchased from third parties and offer limited technological flexibility. The accessibility oversights of software are being made the responsibility of those with limited knowledge or skills in this area, or are being put off as matters of accommodation (which requires students with disabilities to be extremely proactive advocates for their needs and rights).

Accessibility of media technologies, in classrooms and online, is a crucially important issue. Since the advent of online education in the early 1990s, these technologies have been hailed as “liberation technologies” for students with disabilities;8 their inclusive potential, however, is contingent on accessibility measures. In 2010, the Departments of Justice and Education issued a joint letter to universities reminding them of their obligations under the Americans with Disabilities Act and Section 504: “it is unacceptable for universities to use emerging technology without insisting that this technology be accessible to all students.”9 Yet, accessibility problems persist, in classrooms and online.

Scholars and instructors of media studies are unusually well-suited to critical reflection on classroom and course management technologies in their functions as technologies of ability. In our regular use of media screenings and clips, and our experience critiquing media systems, we have two areas of expertise that could better inform the growing integration of digital media in higher education. We are well-positioned to recognize the failures and exclusions of these media, and to advocate for structural changes that make it possible for individual faculty to create accessible learning environments without taking on another full-time job. As this field has been active around the changes brought by digitization to copyright policies,10 so ought we to be active regarding proposed measures such as the TEACH Act, which would create guidelines for the adoption of accessible technologies in higher education.11 Not the realm only of technologists or administrators, the media technologies used in our teaching are deserving of the same attention to power, agency, and exclusion that we might give to popular media and technologies in other contexts.

Image Credits:

1. Elizabeth Ellcessor

2. Elizabeth Ellcessor

3. Elizabeth Ellcessor

Please feel free to comment.

- Lisa Nakamura, “Plug and Pray: Performances of Risk and Failure in Digital Media Presentations,” The Velvet Light Trap 64, no. 2 (Fall 2009). [↩]

- Peter Krapp, Noise Channels: Glitch and Error in Digital Culture (Minneapolis: Univ Of Minnesota Press, 2011), 53. [↩]

- Josh Shepperd, “Infrastructure in the Air: The Office of Education and the Development of Public Broadcasting in the United States, 1934–1944,” Critical Studies in Media Communication 31, no. 3 (February 28, 2014): 230–43, doi:10.1080/15295036.2014.889320. [↩]

- Jeffrey R. Young, Beyond the MOOC Hype: A Guide to Higher Education’s High-Tech Disruption (The Chronicle of Higher Education, 2013). [↩]

- I borrow “bodymind” from scholars of disability, including Alison Kafer and Ellen Samuels. [↩]

- See, for instance: Simi Linton, Claiming Disability: Knowledge and Identity (New York: New York University Press, 1998); Tom Shakespeare, “The Social Model of Disability,” in The Disability Studies Reader, ed. Lennard J. Davis, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: Routledge, 2006), 197–204. [↩]

- Lauren Ingeno, “Online Accessibility a Faculty Duty,” Inside Higher Ed, June 24, 2013, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/06/24/faculty-responsible-making-online-materials-accessible-disabled-students. [↩]

- Norman Coombs, “Liberation Technology: Equal Access via Computer Communication,” EDU Magazine, Spring 1992, http://people.rit.edu/easi/lib/oppo1.htm. [↩]

- Thomas E. Perez and Russlynn Ali, “Dear Colleague Letter: Electronic Book Readers,” June 29, 2010, https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/713149-colleague-20100629.html. [↩]

- See the Society for Cinema and Media Studies’ documentation on Fair Use, for example: http://www.cmstudies.org/?page=fair_use [↩]

- See the following blog post for an overview of arguments for and against the TEACH Act: Cyndi, “Should TEACH Act Language Appear in the Higher Education Act? NCDAE and WebAIM Weigh In,” The National Center on Disability and Access to Education, October 15, 2014, http://ncdae.org/blog/teach-act/. [↩]