Media Fantasies and Moral Panics

Diane Lewis / Meiji Gakuin University

My Cinema Journal article looks at female consumption and the rise of mass culture in 1920s Japan, examining how sensational discourse on female desire was incorporated into the themes and structures of transmedial melodramas known as “ballad films.” In the 1920s, debates about overzealous media consumption preyed on fears about female sexuality, the false promises of the marketplace, and social disorder created by fictions that sparked mimetic desires. While perhaps difficult to recognize today, the heroines of these films are not just victims: their recalcitrance and psychosomatic illness evoke forms of female delinquency that were traced to consumer culture.

For example, in the mid-1920s a rash of crime reports sensationalized the exploits of aspiring actresses. These articles compiled anecdotes of women suffering from “vanity sickness” who flocked to Japanese film studios only to meet with disappointment or ruin. Many hopefuls were robbed, kidnapped, or raped, but reporters suggested that female film fans themselves were to blame for confusing fantasy with reality and ditching their families for dreams of wealth and fame.1 In the early 1930s, Japan’s foremost expert on hysteria, psychologist Nakamura Kokyo, defined its main traits as curiosity, vanity, and mimesis, noting that hysterics frequently confused fantasy with reality.2 The question of who adjudicates the distinction between fantasy and reality, and how, is perhaps at the crux of moral panics over immoderate media consumption.

Since completing the Cinema Journal article, I have been working on Japan-related materials that link media to “aberrant” sexuality via mediations of fantasy. I’m interested in historical understandings of how media, especially fiction, express, explore, gratify, and even implant desires that may not be possible or desirable in real life. This research is helpful for understanding why discourse on excessive media consumption is so frequently expressed as sexual panic.

My article focused on female consumption, fantasies of modernity, and the rise of mass culture, but as others have pointed out, the figure of the moga (modern girl) that was central to earlier media discourses could be compared to the contemporary otaku.3 Both emerged with swift transformations in the mediascape and debates about accompanying social changes and new patterns of consumption. Deviant figures that reconfirmed what was “normal,” they were later re-read and radically transvalued to suggest forms of resistance against oppressive dominant cultures. Redeemers of moga and otaku generally claim for them some kind of “social productivity” so as to legitimate their desires. However, as scholars such as Leo Bersani and Lauren Berlant point out, such strategies devalue, homogenize, or ignore desires and pleasures that are not easily subsumed to political projects.4

The term “otaku”—a very formal way of addressing someone as “you” in Japanese—was first used mockingly to describe diehard anime fans and their awkward interactions in Manga Burriko in 1983. This usage gained wider circulation and darker connotations in 1989 with the arrest of serial killer Miyazaki Tsutomu, whose large video collection made him notorious as “The Otaku Murderer.” This cemented the association between excessive anime consumption and pathological male sexuality. “Otaku” connoted someone unable or uninterested in having “real,” “normal” sexual relations who remained attached to transitional objects.5 In the 1990s, a counter-discourse emerged to counteract negative otaku stereotypes, with Okada Toshio and Otsuka Eiji offering models for understanding anime connoisseurship and promoting otaku as a new cultural elite.

Controversies over otaku fantasies continue. Earlier this year, contemporary artist Aida Makoto excited rancor for his explorations of otaku themes. The Japanese organization People Against Pornography and Sexual Violence (PAPS) launched a complaint against his retrospective at the Mori Art Museum, one of the premiere venues for contemporary art in Tokyo. Aida’s large-scale paintings hyperbolize motifs from Japanese art, history, and pop culture, bringing together the violent and serene with a grandiosity that some describe as moving and others find revolting. Ash Color Mountains (2009-2011) features a traditional Chinese landscape motif of mountain peaks in translucent white mist, which on closer inspection turn out to be heaping piles of dead salarymen, filing cabinets, rolling office chairs, and briefcases. Harakiri School Girls (2002) depicts uniformed high school students disemboweling themselves rapturously. A tightly-knit jumble of figures, entrails, body parts, and fluids within a curiously flattened space, the cramped composition evokes the fukinuki-yatai (blown-off roof) perspective of older pictorial arts while Day-Glo acrylics and holographic foil bring to mind decals vended by gacha gacha capsule toy machines and the low-calorie, high-impact violence of anime and manga.

PAPS complained that the exhibition was rife with harmful images of sexual violence and pedophilia, but singled out Aida’s Dog paintings (1989-ongoing) in particular. Drawing on nihonga techniques and imagery, these show nude young girls with dog collars and leashes wearing bandages where their arms and legs appear to have been amputated. Nevertheless, these girls are “cute”: they have pigtails or ponytails and wear innocent expressions of eagerness, gumption, and placid obeisance. In order to support their argument that Aida’s images “comprise a gross act of sexual discrimination” and even “sexual violence,” PAPS reserved their strongest criticism for the girls’ smiling faces that seemingly suggest consent.6 Aida traces his interest in otaku to the Miyazaki incident and has at times suggested that the alterity of fantasy can be understood as an expression of hostility toward the world that really is. PAPS rhetoric, however, refutes the otherworldliness of Aida’s images, insisting that their violence is quite real and banal.

By contrast, Saito Tamaki’s analysis of otaku sexuality leaves open both the possible threat and instrumentality of that desire: “What otaku enjoy is not making fiction into material form. Nor, as is often claimed, do they derive enjoyment from confusing reality and fiction.”8 Rather, he argues, it is interpretations of otaku culture that conflate the two: “At this point any analysis naive enough to see a direct reflection of reality (genjitsu) in a fictional construct is itself a typical example of confusing fiction and fact.”9 Saito claims, “We do not enjoy fiction because it is a form of virtual reality. We enjoy it because of its status as another reality, one that demands a rearrangement of the subject.”10

Finally, in thinking about moga and otaku desire, fantasy and reality, we should consider the way that “unhealthy” forms of consumption are projected onto specific bodies. It is worth noting that despite evidence that the most visible and active fans of anime are female, the discourse condemning otaku (and redeeming them) focuses overwhelmingly on men. This suggests that the vicissitudes of otaku representation are somehow tethered to broader issues pertaining to changing masculinity, much as the demonization of female consumption in the 1920s was connected to the rapidly transforming status of women in Japanese society and her vital contributions to Japan’s mass media boom.

Image Credits:

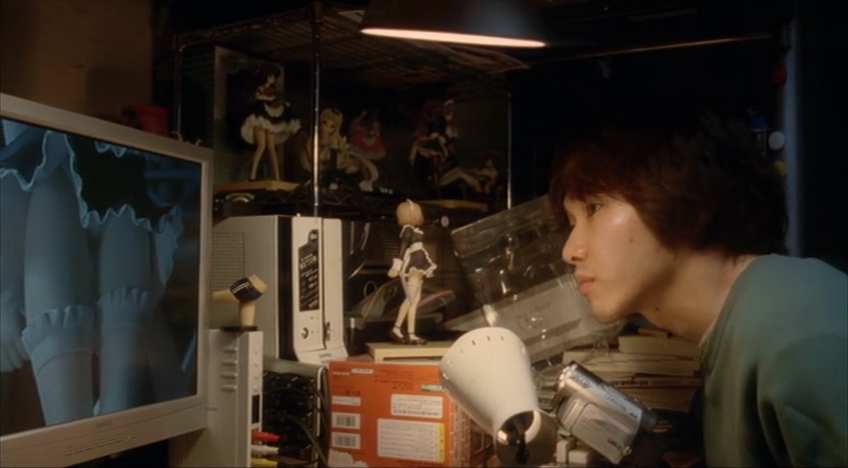

1. Image of an otaku from the film Air Doll (Koreeda Hirokazu, 2009): otaku consumption is coded as “excessive” in order to suggest it is a desperate attempt to compensate for real disappointments, or stems from an inability to distinguish between fantasy and reality, and is frequently portrayed as sexual perversion.

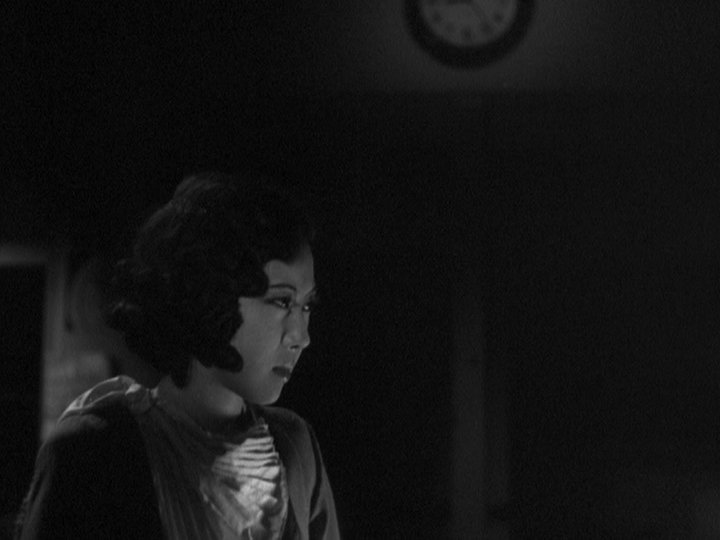

2. Yamada Isuzu as the moga in Osaka Elegy (Mizoguchi Kenji, 1936).

3. Neon Genesis Evangelion, Episode 23, “Rei III.” Original air date 1996 March 6.

4. Ibid.

Please feel free to comment.

- See for instance, in the Tokyo Asahi newspaper, “Young Women Ruined Trying to Become Film Stars, Disobeying Parents Leave for Tokyo without Permission, Tricked into Being Sold off by Studio Chiefs, Relieved of Their Illusions, Tears of Repentance,” December 25, 1925, 7; Matsumoto Yoshiro, “Miserable Aspiring Actresses Lured by the Hell of Vanity!” in Nikkatsu gaho (Feb. 1926): 12-13; Matsumoto, “Dragging Themselves to the Depths of Hell, Aspiring Actresses and their Many Crimes” in Nikkatsu gaho (Oct. 1926): 53-54. [↩]

- Mark Driscoll links this kind of discourse on hysteria in Japan to cultural “ambivalence about how to adjudicate the slippage between opportunity and danger” as women became increasingly independent. Driscoll, Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan’s Imperialism, 1895-1945 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), 89. [↩]

- See for example Melek Ortabasi, “National History as Otaku Fantasy: Satoshi Kon’s Millenium Actress” in Japanese Visual Culture, ed. Mark MacWilliams (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 2008), 274-294. [↩]

- See Leo Bersani, “Is the Rectum a Grave?” in October 43 (Winter 1987): 197-222, and Lauren Berlant, The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008). [↩]

- For more on otaku discourse, see Patrick W. Galbraith and Thomas LaMarre, “Otakuology: A Dialogue” in Mechademia 5 (2010): 360-374. [↩]

- http://paps-jp.org/action/mori-art-museum/statement-english/ Accessed 2013/5/7. [↩]

- http://paps-jp.org/action/mori-art-museum/kaitou_response/comments-on-the-reply/ Accessed 2013/5/17. [↩]

- Saito Tamaki, Beautiful Fighting Girl, trans. J. Keith Vincent and Dawn Lawson (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 20. As Vincent writes in his translator’s introduction, “In Saito’s reading, then, the beautiful fighting girl [the bishojo who populate anime and associated media] is not a reflection of a sociological reality or even of a desire for a certain reality but a perverse fantasy that functions to recathect and invest with a new reality, to ‘animate,’ as it were, a sexual object that threatens to dissolve into fiction.” Vincent, “Making It Real: Fiction, Desire, and the Queerness of the Beautiful Fighting Girl” in Beautiful Fighting Girl, xi. [↩]

- Ibid., 158. [↩]

- Ibid., 162. [↩]

Pingback: Tech Anxiety is for Rich People | A Day Job and a Dream