The Walking Straight: Queer Representation in The Walking Dead

David Greven / University of South Carolina

The Walking Dead, a thrilling, somber zombie show that is AMC’s biggest ratings draw, presents an image of a bleak zombie heartland America in which very few human being exist. Overrun by the titular creatures, this America is mostly empty and depopulated, barren, a vast, sprawling, and desolate landscape. In the second season episode “18 Miles Out,” the dark, hotheaded Shane (Jon Bernthal) stares out from a car window at an immense field in which one solitary walker makes his lurching way; on the way back, Shane sees the same zombie, still moving in the same indefatigable and hopeless manner. The cyclical, neverending hunger and blankness of the zombie is once again an apt metaphor for a mindlessly consumerist America, recalling George A. Romero’s great bleak satire Dawn of the Dead (1978).

The zombies here are also a metaphor for a new and profound—stemming from 9/11, no doubt, and George W. Bush’s Presidency, certainly—social disillusionment in the nation. The entire second season was about the loss of a child, a young girl named Sophia, the search for whom was also clearly a metaphor for the search for hope. She turns out to have been under the noses of the protagonists the entire time—what remains of hope lives in a barn, and is a zombie child.

Nevertheless, for all of its fairly intensely sustained bleakness, The Walking Dead is primarily about survival and the creation of new kinds of social arrangements. The main characters of the series—and for the most part, despite the inevitable deaths, most of these have remained on the show—are, generally, former strangers who have forged new and unshakable bonds due to the mayhem. While arguments and tensions abound, the group of survivors whose plight we follow are a remarkably tight-knit group, a motley crew that recalls the stock 1940s bomber movie, consisting of recognizable “types.” These types also evoke conventional tropes of the Western genre, which The Walking Dead emulates at every turn, very much a key example of what Robert B. Ray has called “the concealed Western.”

To get to my thesis right away, The Walking Dead painstakingly represents different racial and ethnic, religious and cultural types. While its track record on African American characters is wobbly, the current season features the potentially spectacular presence of the black woman warrior Michonne (Danai Gurira), a legendary character from the comic books who wields a sword and walks around with two zombie slaves literally attached to her hip (clearly, a volatile piece of representation that will need continued attention). While the show’s track record on strong women characters is generally hit or miss, they have certainly been present. The series also features an Asian-American in a prominent role, the Steven Yeun’s hot-rodding Glenn.

What the series does not have in any way, shape, or form is an explicitly queer character. Given that the zombie genre often presents its survivor heroes as a representative swath of humanity, the omission of any queer characters is somewhat surprising and certainly disappointing.

Many Westerns privilege the family as the chief social structure, and show this family as threatened, endangered, torn asunder. At the same time, the narrative strives to restore the family. Marriage emerges as a key structuring principle in this regard, being what leads to family and remains at its center and allows it to function. As Laura Mulvey has shown, using John Ford’s classic western The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) as the model, the Western often pits a terrible villain against two heroes; one hero is a loner who maintains ties to the land and goes his own way, while the other is idealistic, socially conscientious, upstanding, and married.1

The Walking Dead replicates this structure fairly closely, if we read the zombies as the terrible villain, Rick Grimes (Andrew Lincoln), a small-town sheriff who now uneasily leads his group of survivors, as the upstanding family man who embodies the law, and Shane Walsh (Jon Bernthal), who had been Rick’s police officer-partner, as the increasingly turbulent loner. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s classic paradigm of triangulated desire applies here beautifully, as both men war over one woman. This woman, Lori (Sarah Wayne Callies), Rick’s wife and mother to their son Carl (Chandler Riggs), is an interesting, tough-minded character in her own right, widely disliked by the fanbase but, in my view, an appealingly idiosyncratic presence.

When Rick was believed dead (he had been shot right before the zombie crisis began by a would-be prisoner, and Shane blames himself both for the shooting and for leaving Rick in the hospital, now overrun by zombies, to die), Shane protected Lori and Carl, and with them eventually joined the survivors we get to know. Rick, not dead after all, eventually meets up with Shane, Lori, and Carl; it is not until the second season and a great deal of anxious, brooding handwringing that Lori finally tells Rick about the affair that she had with Shane when they all believed Rick had died. By this point, Rick and Shane are no longer friends but close to enemies; by season two’s end, Shane tries to kill Rick, but Rick kills him instead.

All monsters are queer metaphors, to one degree or another, existing as they do outside the social order and persecuted by it. One could read the zombies as the queer element of The Walking Dead, a group of society’s rejected and disenfranchised. Moreover, once bitten by a zombie, you become one, which might be read as a variation on the theme of the corrupting influence of the predatory homosexual.

I am going to argue that what makes The Walking Dead a queer show is its queering of masculinity, specifically the character of the aptly named Shane, who recalls the loner hero of the classic Western. The most highly charged dimensions of The Walking Dead along queer lines are now no longer part of it, of course, since Shane was killed off at the end of season two. Especially as played by Bernthal, Shane as well as the Rick-Shane relationship and the triangulated desire for Lori, are all rendered in a suggestive manner for queer interpretation. As Bernthal plays him, Shane, emotionally volatile, dark, hirsute, wiry, has a palpable carnal edge and edginess, an almost overripe sensuality within his muscled physique and his ardent, angry, embattled personality.

As I have argued elsewhere, masculinity in contemporary film and television is usually represented as a split between two heroes, “double protagonists,” one of whom is a narcissist, the other a masochist.2 Shane is the narcissist here, morally upright and troubled, Rick the masochist. But in many ways these roles bleed into each other, as well; certainly, Shane comes to seem quite masochistic as well as he pines for the increasingly remote (though later troubled and lovelorn) Lori.

What we have in The Walking Dead, then, is a resolutely non-queer show in terms of content that has some deeply queer elements in formal terms that include acting styles. The Walking Dead is an exemplary instance of the queering of masculinity that has characterized male representation in the past two decades.

This queering of masculinity is a subtle but palpable one. For example, in the opening shots of “Save the Last One” (2.3), written by Scott M. Gimple and directed by Phil Abraham (original airdate October 30, 2011), a shirtless Shane stares at himself in the mirror, and proceeds to shave off his hair. This episode reveals that Shane killed Otis, a member of the farmhouse community that the survivors join in the second season.

The killing of Otis is both terrifying and a moral muddle. On a deer-hunting mission, Otis accidentally shot Carl; Shane and Otis volunteer to go to the high school, overrun by zombies, where a medical team had been set up and medical supplies, such as a respirator for the dying Carl, might still be found. As will be revealed by episode’s end, Shane, limping from a fall, and Otis, medical supplies in hand, are desperately fleeing from hordes of zombies when Shane decides to shoot Otis and thereby both save himself and Carl, Otis’s body serving as a distraction to the zombies that allows Shane to escape and also to bring back the supplies.

The scene of Shane shaving is the aftermath to the killing of Otis but the start of “Save the Last One.” As the start, it casts a queer light over the entire episode, which includes a scene between the the main heterosexual couple, Rick and Lori, in which they debate if children belong in this world any longer. The series usually begins with a prologue that is then followed by the opening credits of the series each week. This episode’s version of the prologue is entirely dedicated to the scene of Shane’s saving, but an entire discourse of Shane’s character and relationship to the other characters and to the series is created through montage.

First, there is a shot of a showerhead from which water spews that seems to be turned on without the agency of human hands. There is then a shot of a framed mural, a scene of an idyllic country setting with the words, “Wherever you wander, wherever you roam, be happy and healthy and glad to come home.” There is a shot of bloodied overalls on a toilet seat, with a gun resting on top of them. Then, we get intimate shots of the backside and arms of a muscular strong man, and see him shaving off his hair with a razor. It is revealed that the man doing the shaving is Shane.

The shot of the showerhead, at this point, cannot fail to remind the audience of Psycho (1960) and of the bathing and soon to be murdered Marion Crane. If Hitchcock’s legendary scene is a shockingly stylized representation of horrible violence, it is also a sexually charged scene that derives its transgressive allure, especially for its era, from the promise of seeing a beautiful young woman in the flesh. One also thinks of Brian De Palma’s frequent variations on the scene. Here, though, there is no beautiful young woman, but, instead, a hot dark muscled guy with a brooding intensity, alone. The mural with its homespun design and saying is an ironic counterpoint to the scenes of zombie mayhem all around the characters, from which the farmhouse seems like a respite. But it also provides a counterbalance to the strange, sultry, threatening presence of Shane, emphasizing his outlier status in the cozy heterosexual familial world.

The shot of the bloodied, removed clothing on the toilet seat alerts us to the fact that someone has disrobed, while the gun on top of them signals murderous phallic potency. Someone is naked and loaded. When we do see that it is Shane in the mirror, there is an odd effect created by the fact that he is breathing heavily and audibly. I would argue that altogether the scene has a masturbatory intensity and evokes autoerotic self-regard.

Clearly, a great deal more needs to be said about this episode, to say nothing of the series and of the question of queer representation. To emphasize Shane’s almost pansexual allure, he is paired up with Otis, who in physical terms makes for a striking contrast. Otis is portly, shambling, not conventionally attractive, and not athletic, as he informs Shane openly when they try to escape from the zombie-packed school gym. There is a similar maneuver in Lasse Hallström’s Casanova (2005), starring Heath Ledger and the titular seducer. Either to emphasize—or to diminish and thereby render safe—the immense sexual charge of Ledger in the role, the film pointedly juxtaposes the seductively handsome Casanova against a wealthy man from Genoa, Paprizzio (Oliver Platt), whose vast girth and physical unattractiveness are emphasized repeatedly. I would argue that such physical mismatchings are designed to quell the homoerotic tension that might be made too apparent in male-male pairings.

At the same time, the relationship between Shane and Rick, a handsome man in distinct ways, deepened by the theme of triangulation, is another potentially site for queer pleasure in the series. Other characters, shown to be variously solitary and cut off from the group as well, such as Laurie Holden’s Andrea and, especially, Norman Reedus’s Daryl Dixon, a fan favorite, are potentially readable as queer. While Andrea and Shane hook up at some point, Daryl has never been shown to be motivated by sexual interest in any other character, including Sophia’s mother, Carol Peletier (Melissa McBride), who clearly feels for Daryl. In the opening episode of season three, their flirtation is brought up but is largely played for laughs and left notably non-committal.

For now, let me suggest that The Walking Dead is in keeping with genre shows generally in having no queer characters. Shows as varied as Star Trek, Alias, Fringe, Smallville, and Breaking Bad never feature queer characters. What they do at times feature is queer allegory and stylization and the destabilization of gender roles. The questions to raise are why queer genders are so prevalent in genre shows, and is this queering of gender sufficient in the absence of anything more explicit?

Image Credits:

1. Male-male intimacy on The Walking Dead

2. Glenn, played by Steven Yeun

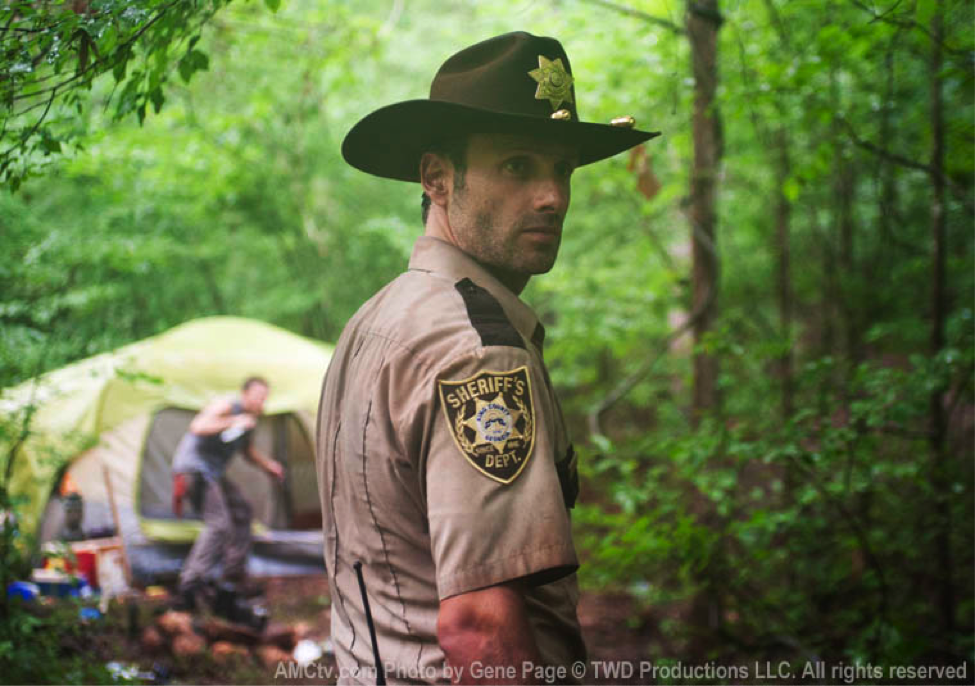

3. Rick, the embodiment of the law

4. Otis’ death with Shane

5. Shane looks at self in mirror

Please feel free to comment.

- Mulvey, Laura. “Afterthoughts on ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ inspired by King Vidor’s Duel in the Sun (1946).” Feminist Film Theory: A Reader. Ed. Sue Thornham. New York: New York UP, 1999. 122-131. [↩]

- Greven, Manhood in Hollywood from Bush to Bush (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2009). [↩]

This is a great and thoughtful piece, David. Thank you for offering more dimensions of the character I miss the most. I’m racking my brain to think of any queer characters in any zombie texts and can’t (though I know at least one exists from an article I read last year). I’m fascinated, though, by your rendering of queer allegory and stylization.

Pingback: The Walking Straight: Queer Representation in The Walking Dead David Greven / University of South Carolina | Flow | Screenagers.me

I read half of your article and stopped. Now I’m assuming you are homosexual if not its all the same you are what gives gays a bad reputation here’s my points you complain of the lack of strong female characters and point out that the africancharacters are not prominent enough and there are weak minorities in the show basically correct?.. K it’s based off of a comic book where the characters ethnicities and roles were previously chosen incase you we’re unaware.. It’s clear your mined is that towards a strong liberal sense and you put your focus on the harsh injustices of he cruel world and how everything is dominated by he tough masculine male oh no shucks…. The zombies in the show represent queers that bite people and turn them… Wtf is wrong with you clearly you read to deep into hints on a level in which you may want to check your sanity your the type of gay I would never want to meet or talk to or be around cause your a moron simply put. I’m sure a lot of gay men and women watch the show even bough there is yet to be a gay character you act like all the characters are homophobic or something. I guess I could end by reminding you it’s a show about a zombie apacolypse so having a random gay character in it to show t hat the creator is a true liberal patriot i guess that makes sense he should also make sure to include gays blacks Asians Indians and handicapped and strong feminist women in it to to make sure all the sensitive whiners in these groups feel included too!

This article makes several good points about the lack of queer characters in The Walking Dead, especially now in season 3 given that Merle has often joked about the Andrea-Michonne relationship as being sexual in nature as a way of provoking anger. These comments draw more attention to the fact that there is not a single explicitly queer character in the show. I debated a bit about whether or not to engage with the commenter above me, and I don’t want this to be the focus of my response, but I do think that the commenter missed the point. Sure, “gay men and women watch the show” without there being gay character, but that’s not the point. To think that the inclusion of a gay character would be simply in service to a liberal agenda is simply close-minded and ignorant.* The Walking Dead has never included queer narratives with minor characters or the passing tragic stories of strangers we sometimes glimpse. Before these jokes of Merle’s, it was almost as if The Walking Dead existed in this strange world in which gay people do not or never have existed, and that’s not the world we live in. I know it’s a genre show, but the inclusion of zombies should not have an effect on who people love, and the Michonne-Andrea jokes of Merle only serve to make the absence more pronounced.

Speaking of Andrea, I also think it’s worth examining the masculine/feminine dynamic in relation to the Governor’s two closest relationships, Andrea and Milton. It’s interesting that Andrea’s sexuality plays a large part of why she and the Governor are close, but her power–and here I’m speaking of her strength, typically a male domain–is especially pronounced when she is put in juxtaposition with Milton, who is very meek and passive. I’m thinking both of scenes in Woodbury when he is asking for her to intercede and she uses that as a leadership–also typically a male domain, ESPECIALLY on this show–opportunity, as well as when they are fighting in the woods. It’s interesting to me because this meekness (feminization) of Milton is often used to show him as a character who is weak, incapable of surviving in this new world without masculine figures such as the Governor or sometimes Andrea. Meanwhile, Andrea’s case is perplexing because while she does grab for leadership it is sometimes unclear as to whether or not the narrative of the show wants viewers to believe that Andrea is capable or not. While Woodbury seemed inspired by her speech, the effect on the text on the audience was somewhat less so. The queering of gender in Milton’s case is used negatively, but if with Andrea if we are to respond positively to her taking the show’s typically masculine leadership role then it seems to speak to a devaluing of what the show establishes as “feminine” qualities, though if we are to respond to her speech negatively then the show would be using queering of gender as a device to condemn characters.

It seems that either way, we lose.

*Also to respond to the idea that The Walking Dead is too heavily based on the comic books, that’s no excuse. The show has shown plenty of ability to change the plot and characterization from the comics when it so desires.

Intriguing article. Great points about Otis and overall representations of homosexuality on mainstream television and the “Walking Dead.” This pushing the envelope is characteristic of overall quality television. However, I cannot help but wonder if these issues are not as cutting edge as the author supposes. Science fiction and post-apocalyptic fantasy have always been an arena for transporting important social issues to a foreign landscape. Think Jules Verne, “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea,” H.G. Wells’ “The Time Traveler.” Certainly, these are very great points, but probably nothing new.

Pingback: There Has Been Blood: Horror-Comic Masculinity in The Walking Dead David Greven / University of South Carolina – Flow