Faux Gender and the New Popularity of Drag Culture

Keara Goin / FLOW Senior Editor

While performative drag and its correlated culture has been part of the LGBT community since before the now infamous Stonewall Riots, there has been a recent exponential explosion of drag within mainstream popular culture. Much of the US has been introduced to the world of drag through drag superstar RuPaul, first as a popular culture icon and then through her/his hit Logo network shows RuPaul’s Drag Race and RuPaul’s DragU. And while my own loyalty and devotion to the art, and I do mean art, of drag performance has deterred me from even approaching analyzing Drag Race, the emergence of DragU, the show’s spin off, and its subsequent destabilization of hegemonic constructions of gender has prompted me to write this post. Judith Butler’s innovative scholarship on the performative reality of gender, as exemplified through the practice of drag, revealed the fallacy of essential gender and sex, and furthermore exposed how all of us, as humans, “do” our identity as opposed to “are” our identity. DragU takes this critical interjection to a new degree, and shows how all gender is faux gender. Said best by the grand dam of drag herself, “you are born naked, and everything else is drag” (RuPaul Charles).

Shortly after the second season of the run-away success Drag Race, Logo began airing what they felt was the natural spin-off of the hit series: DragU. The premise of the show follows the franchise’s most popular queens as they work to transform “biological women” through what RuPaul has deemed “the miracle of drag.” Put simply, it is a show where men who look like women teach women how to be “women.” However, as the queens work with each contestant, they work on more than their brow arches and cleavage, they attempt to inspire within these women a sense of confidence and self-esteem. And in teaching them how to be the ideal, and above all fierce, woman they see in them, the queens dissolve essentialist notions of gender and replace them with a suggestion that being a “woman” can mean anything you want it to mean. Normally not one to wax poetic over a reality show, especially one that can potentially be seen as a masquerade of the art of drag (I am aware of the irony in this statement as masquerade is a fundamental aspect of drag performance), I nevertheless find in it important ruptures in the fabric of gender ideology. DragU, through the use of a culture that is more familiar to some than others, shoves the construction of gender in our faces and demands that we see it for the fallacy it is.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T52mscQcpzg[/youtube]

In Judith Butler’s own analysis of drag, she discusses the film Paris is Burning and its depiction of the New York City ball scene which includes, among other aspects of 1980s gay culture, performative drag. She posits that as a “deconstituting” practice, within drag “the ideal that is mirrored depends on that very mirroring to be sustained as an ideal”1. Her contention is that drag proves, by its ability to exist, the constructed reality of gender; femininity is constituted by what is seen as femininity. Not an innate feature of birth, a person’s gender is ascribed, self-identified, and reinforced through gendered behavior. For Butler, “Gender is not passively scripted on the body, and neither is it determined by nature, language, the symbolic, or the overwhelming history of patriarchy. Gender is what is put on, invariably, under constraint, daily and incessantly, with anxiety and pleasure”2. Drag unmasks this process, and asserts that, by collapsing supposed gender opposites, that gender is a performative role, with society as its playwright.

Certainty, Butler’s analysis applies to Drag Race in a direct and unproblematic fashion. However, when we inject DragU into the equation, we can see that there is something very different going on with the practice of drag. It is because drag queens (appearance aside) for the most part identify themselves as men, what is being transferred from them to what they call “biological women” is a femininity that is framed within notions of masculinity. Moving clearly beyond the increasingly less taboo and mainstreamed practice of “normative” drag—a reality that Butler probably could never have foreseen—DragU is more than the unsettling of gender and femininity that we see in more classic and popular forms of drag. The representation of women performing feminine drag initiates a second level of unsettling, where not only is the performance a reflection of the absence of an ideal to performatively and bodily imitate (as Butler correctly asserts traditional drag does), but critically ruptures and exposes the influence of certain kinds of masculinity on what it is to perform femininity. Subsequently, DragU should be taken as a unique text with a specific comment on gendered identity apart from that of traditional drag.

I leave you with the drag artist Morgan McMichaels and her/his recent performance at a club in Southern California where, she/he transforms her/himself from an already transformed queen back into a “boy.” While lip-syncing to Beyoncé’s “If I Were a Boy,” Morgan demonstrates, through her/his performance, that all gender is faux gender, and imparts a symbolic interpolation that defies the reduction of what she/he does to mere fancy. Drag may be camp, it can be raunchy, and it is almost always entertaining, but it is, most importantly, fundamentally a rejection of hegemonic and normalized constructions of gender that is beginning to play out in new and even exciting ways.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rpd7ZbEYyn8&feature=youtu.be&a[/youtube]

Image Credits:

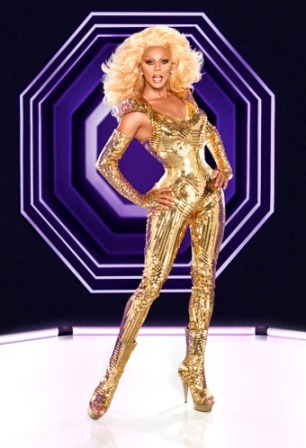

1. RuPaul’s DragU Professors

2. RuPaul Charles

3. Professors Morgan, Chad, and Willam

Please feel free to comment.

Why are there no dates on this article? Is this an oversight or is it deliberate?