David Lynch’s Secret Passages

Akira Mizuta Lippit / University of Southern California

Most of Lynch’s films depict the passage from one side to the other, this world to that, the world above to that below, night to day and day to night. Some films seem to take place exclusively on one side or the other (but even then always with an awareness of the other side), or entirely on the other side: Eraserhead, Dune (1984), Wild at Heart (1990), The Straight Story (1999).1 Even then, the passages are visible: the radiator in Eraserhead, as well as other quasi-imaginary topographies; the expression of interior monologues in Dune (a technique that recalls one of Lynch’s favorite films, Sunset Blvd.); the recourse to Victor Fleming’s The Wizard of Oz (1939) as an exaggerated referent and framing device in Wild at Heart; the environmental transformation (of everyone and everything around him, including the scenery and the weather) of Alvin Straight’s tractor-induced travel in The Straight Story.

In Wild at Heart, the diegesis takes place entirely over there, elsewhere. Although the film follows in the path of The Wizard of Oz, which it invokes frequently and openly, “home” remains elusive within the diegetic spaces of the film. The title suggests a refusal of domesticity, or a failed domestication; in Lynch’s film, the domicile itself falls apart. Home is not possible because it is, in Wild at Heart, a place of abuse, terror, and deep, irrevocable unhappiness. It is where Lula Fortune (Laure Dern) was raped, her father betrayed and murdered by her mother. It is where Sailor Ripley (Nicolas Cage) learned to smoke (at age four, shortly after the death of his mother from lung cancer), where his parents rarely were. It is a place banished from reality and constituted in its absence, as an absence in the fantasy that envelopes Sailor and Lula and forges their relationship. For it to be possible at all, home has to be established on the other side, an anti-home, “no place like home,” or rather, home can only ever be a place “like” home. An anahome, a synecdoche of home, its simile. The impossibility of the return home in Wild at Heart prefigures the horror of home in its sibling work, “Twin Peaks”. In a sense, the films and TV series–Wild at Heart, “Twin Peaks“, and Fire Walk with Me–which overlap at different points represent passages to each other, opposite sides of the world, opposite worlds divided by sides, Sailor and Cooper, Lula and Laura. “Wild at Heart is,” says Todd McGowan, “The Wizard of Oz without Kansas”; a world in which the fantasy of Oz has completely subsumed the absence of fantasy and desire: it is a world constituted, according to McGowan, entirely by fantasy.2 By contrast, “Twin Peaks” is a world of desire, an endless and inescapable home without fantasy; there is no way out of the totalizing and brutal forces of desire, only a passage to the other side, death.

In most cases Lynch’s passages involve a secret route from one side to the other. The portals can be passages, places, objects, fantasies, or figures. Lynch’s films are filled with corridors, passages real and imaginary, portals, openings, and orifices that serve as points of entry and departure. “Secrets and mysteries,” says Lynch, “provide sort of a beautiful little corridor where you can float out and many, many wonderful things can happen in there.”3 The radiator and bed in Eraserhead; the freak show in The Elephant Man, and the multiple points of entry into John Merrick (John Hurt); the spice Melange in Dune, which extends life and folds space–the worms themselves (their needled orifices); the ear, the closet, and the joyride in Blue Velvet; dreams (in almost every Lynch film), Laura Palmer’s diary, the killer’s letter codes beneath each victim’s nail, Dale Cooper’s tape recordings to “Diane,” the Red Room and Black Lodge in “Twin Peaks”, the photograph on Laura Palmer’s bedroom wall in Fire Walk with Me; the prison cell for Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) in Lost Highway, but also the videotape, video camera, intercom, photograph, pornographic film, and cell phone (the Mystery Man); the tractor in Straight Story (1999), as well as the nighttime sky; the key and the cube in Mulholland Drive; the rabbit theater and movie set in Inland Empire. And sometimes reversals, forward and backward, in “Twin Peaks” (reverse motion in the Red Room) and at times in Lost Highway. Also the reversible palindromes in “Twin Peaks”, “Wow, Bob, wow,” or even just “Bob.” (Of Bob, Lynch says: “Something strange is happening when Bob is around. There are, maybe, some worlds coming together. … There’s like a wind or a disturbance, and openings for different things to come in.”4 )

Everything and every place provide passage in Lynch’s diegeses, every movement (of people, of cameras) a passage, each passage secret even when explicit, explicit in its secrecy. Everywhere that Henry goes in Eraserhead forges a passage: into and out of his apartment (into corridors, elevators, rooms, through doorways, entries and exits), toward and into Mary’s house, into and out of dreams, fantasies, nightmares, and other topographies. It is as if he creates portals in space just by moving his body, as if his body didn’t belong in the place where it happens to be. Henry bores holes in space. In The Elephant Man, the camera enters at one point into the eyehole of John Merrick’s one-eyed (cycloptic) hood and prosthetic surface, passing into a displaced psychic zone of industrial ducts, factory scenes, the disappropriated dream of his mother’s “rape” by elephants, and the nightmare of John Merrick’s beastly nocturnal visitors who bring a mirror that reflects not only Merrick’s prohibited visage (no mirrors are permitted in his hospital room) but also his face as that of an elephant, the same elephant perhaps that assaulted his mother. Every movement in Blue Velvet–Jeffrey Beaumont’s (Kyle MacLachlan) strolls interrupted by the severed ear he finds en route, his secret entries into and out of Dorothy Vallens’s (Isabella Rossellini) apartment, into and out of her body full of holes, into and out of Frank Booth’s world–feels marked as a passage, a transition, a fundamental transformation. Everywhere throughout Lynch’s cinema, movement seems to mark a passage, opening space where there are neither spaces nor openings. Here, everything becomes a threshold, anywhere a potential transition to somewhere, nowhere, or simply elsewhere. Invisible spaces in Lynch’s cinema are plastic spaces.

Blue Velvet begins in the sky and quickly slowly drops beneath the surface of the ground. (Fast and slow, the unique temporality of Lynch’s cinema.) It moves up and down, in and out, before and behind, across the thresholds of this world and that. From the plastic blue of the Lumberton sky to the opaque underworld teeming with Frank Booths and insects. Of his childhood worldview, Lynch says: “I learned that just beneath the surface there’s another world, and still different worlds as you dig deeper. I knew it as a kid, but I couldn’t find the proof. It was just a feeling. There is goodness in blue skies and flowers, but another force–a wild pain and decay–also accompanies everything.”5 In the end, in the ends of Lynch’s cinema, there is no proof, only passages between one world and another, one world and all the others. Secret passages beneath the surface that one never finds but feels; passages to and from feeling whose very existence remains “just a feeling.” Blue Velvet is full of secrets; agreements, promises, undisclosed knowledge. Dorothy calls Jeffery her “secret friend,” then later, her “secret love.”

(On cinema: “The neat thing about film is that it can tell a little bit of a certain side of that thing that words couldn’t tell. But it won’t tell the whole story, because there are so many clues and feelings in the world that it makes a mystery and a mystery means there’s a puzzle to be solved. Once you start thinking like that you’re hooked on finding a meaning, and there are so many avenues in life where we’re given little indications that the mystery can be solved. We get little proofs–not the big proof–but little proofs that keep us going.”6 Cinema provides “little proofs,” little fragments of proof that never give the entire meaning of the puzzle, but just enough to “keep us going.” A perpetual mystery, a perpetual puzzle fueled by little proofs. Cinema is, for Lynch, a “feeling.” One would like to say a secret feeling, a feeling for secrets, ultimately a secret world.)

Secret passages also open up in the body, second (secondary originary) orifices inside of orifices, in ears, eyes, mouths. John Merrick’s entire body is such a secondary originary orifice, as is the extra ear in Blue Velvet. Of the ear that Jeffrey Beaumont finds in Blue Velvet, a ear that becomes a trope, a way in and way out, as a later shot reaffirms when a slow zoom out from Jeffrey’s ear finds him transformed into his father in an Aloha shirt, napping on a lawn chair (a shot that appears to return in Lost Highway, when a dazed Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty) awakens in his yard, apparently confused from his own transformation), Lynch says: “It had to be an ear because it’s an opening. An ear is wide and, as it narrows, you can go down into it. And it goes somewhere vast …”7 Everything passes through Jeffrey, in one ear and out the other; he becomes himself a bridge between separate worlds. Between the worlds inhabited by and represented by Frank Booth and Sandy, Jeffrey is, says Lynch, “the only bridge between the two.”8

Michel Chion adds: “A bridge between worlds, between scales, between violence and a still more terrible apathy, between speech and silences, between dismembered parts that look as though they will never make a whole: it pleases me to think that the line in whose form Lynch the artist thinks of and draws himself–a cord, coupling, link, bit, log–is also the line that makes a bridge.”9 Lynch’s bridges connect disparate spaces within each film, but also the heterogeneous spaces between films and between his films and the outside world. Regarding the specific nature of Jeffrey’s bridging, Lynch says: “Jeffrey can connect different worlds. He can look into Sandy’s world, he can look into Dorothy’s world, he can get into Frank’s world.”10 Jeffrey connects the disparate worlds of Blue Velvet, named as such by Lynch through a transgressive visuality, an ability to look across worlds and to connect and enter those worlds (“get into,” says Lynch) by looking into them. Jeffrey’s connectivity is specular.

Image Credits:

Note: All images are Screen Captures from Lynch’s works

1. Dune, Dune

2. Agent Cooper’s Dream, “Twin Peaks”

3. Man From Another Place, “Twin Peaks”

4. John Merrick, The Elephant Man

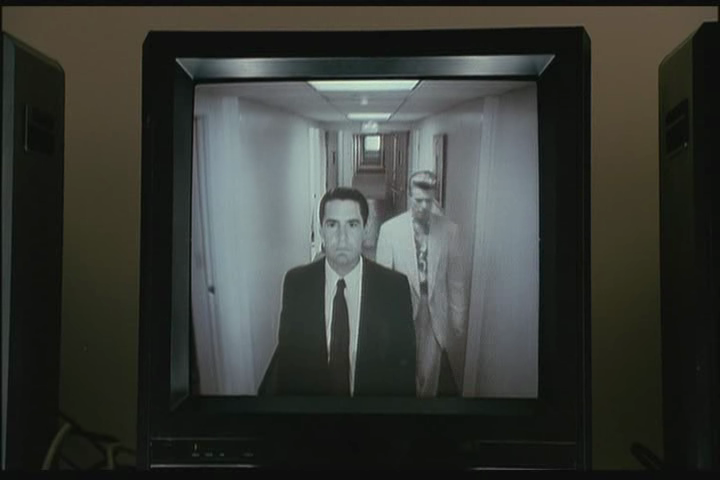

5. Metamorphosis, Lost Highway

Please feel free to comment.

- On the other world of Eraserhead, and of the experience of making and inhabiting it, Lynch says: “That’s why Eraserhead was so beautiful for me because I was able to sink into that world and live in there. There was no other world. I hear songs sometimes that people say were popular at the time, and I haven’t a clue, and I was there. And that’s the most beautiful thing–to get lost in a world” (Lynch, Lynch on Lynch, 27, original emphases). [↩]

- McGowan, The Impossible David Lynch, 111. [↩]

- David Lynch, Inner Views: Filmmakers in Conversation, ed. David Breskin (Boston: Faber and Faber, 1992), 95. [↩]

- Lynch, Lynch on Lynch, 74. [↩]

- Lynch, Lynch on Lynch, 8. [↩]

- Lynch, Lynch on Lynch, 26. [↩]

- Lynch, Lynch on Lynch, 136. Ears play a vital role in Lost Highway as well. Michel Chion notes: “In Lost Highway the only thing that jazz saxophonist Fred Madison, an adult living with his wife in a beautiful, empty house, has in common with (his double? mask? alter ego?) Pete Dayton, a young mechanic living with his parents, is that both actively use their ears, the first as a musician, the second as an expert in the art of sound to identify what is wrong with a car engine. As ‘Mr. Eddy’ puts it, after asking Pete to find a solution to a mysterious noise in his beautiful car, ‘the best goddam ears in town’” (Michel Chion, David Lynch, trans. Robert Julian [London: British Film Institute, 2006], 202, original emphasis). [↩]

- Lynch, Lynch on Lynch, 139. [↩]

- Chion, David Lynch, 203. [↩]

- Lynch, Lynch on Lynch, 141. [↩]

Hello,

Thanks for this nice written article. You can find some news on my Lynchland FaceBook Page about David L. : http://www.facebook.com/lynchland

Roland Kermarec / Lynchland

This was an awesome article to read! It’s interesting how you describe the mouths of the sandworms as portals, as I always felt that the Baron’s demise came off as him entering and being locked into the void rather than eaten. What’s also fascinating is how the sandworms of Denis Villeneuve’s Dune seem to also have portal like mouths, as is evident when the beast seems to suck in rather than chew upon the spice harvester. In fact, I even think Villeneuve has taken David Lynch’s concept further by making the mouth of the worm look like an eye (the teeth looking like an Iris and the dark center representing the pupil). As the saying goes, “The eyes are the window to the soul.”