Spying while “Black”: The curious failure of The Undercovers

Camille DeBose / DePaul University

When I proposed writing this article I was intrigued by the notion that one of our current media darlings, J.J. Abrams had somehow stumbled while employing what could be considered a fail proof formula. A spy show. Action, intrigue, car chases and gunfights are usually well received when properly executed and our man J.J. seems to have no problem executing. From minute one of the first episode to the final minutes of the last (aired) episode, Undercovers played consistent with its genre and budget. There were high production values, great cinematography and pleasingly appropriate musical scores which complemented the exotic or international localities. The Blooms are television spies, pure and simple. The missions are filled with intrigue. The bad guys are nasty and the sidekicks are humorous. As I watched I was reminded of shows I enjoyed growing up in the eighties. Hart to Hart, which aired from ‘79 to ‘84 followed the exploits of a wealthy husband and wife team who fancied themselves detectives in their “secret” lives. Moonlighting also came to mind which starred a young Bruce Willis and Cybill Shepard. While the “cases” were important to the show the relationships between the male and female lead were equally important and explored throughout the episodes.

The Undercovers is clearly a relative to these shows. Steven and Samantha Bloom are attractive and comfortable and capable of pulling off an Irish accent. They live in a modern home with a kitchen adorned with orchids and hanging copper cookware. I actually laughed out loud during a scene where their “handler” Shaw, after showing up at their home unannounced and partaking of Samantha’s french toast, declares it too dry. Steven’s impassioned response is “…that’s because you overheated it!…” The mood of the show is that combination of drama and comedy christened “dramedie” in the eighties. Each episode requires the Blooms’ to travel to a faraway destination designated by a corny-but-cute postcard transition. While on their missions I watched the Blooms speak French, Portugeuse, Spanish, Russian and several other languages. The objectives were formulaic but fine. One episode included diamonds (expected) that weren’t diamonds but crystalline poison cut to look like diamonds for easier transport. OK. That’s pretty clever. Mind control was the subject of one episode while a brilliant scientist forced to create a miniature bomb was the subject of another. Throughout the season there are foot chases, plenty of fights and shots fired and several bad guys go down. Shadowy figures meet in shadowy locations exchanging furtive glances while hatching dark plans our heroes must thwart. With the opulent settings and fun disguises I kept waiting for the show to get… bad. But the shark jumping never came. Let me unambiguously state, The Undercovers is not the most brilliant show on television. I’m not sure what show that would be, though The Booth at the End makes me tingle. Nor is it the worst. The Undercovers, I’ll reiterate, is a pretty lighthearted spy dramedie with high production values, attractive leads, silly postcard transitions and a secret. We’ll never know the secret because the show was canceled.

So what happened? One theory, presented by a viewer not particularly impressed with the show, is the lead roles were played by people who’s names “can’t even be pronounced,” (Boris Kodjoe and Gugu Mbatha-Raw). We’ll bracket that theory for now. A few viewers argued the show did not contain enough depth, intrigue or “edginess.” This is true-ish. The show is not dark and dramatic so the assertion that it lacks “edge” is a fair criticism. There were complaints about not enough “chemistry” between the two leads making me wonder if the absence of a hypersexualized portrayal hurt the show in some viewers’ eyes. Steven and Samantha are clearly devoted to one another and reaffirm their love at the end of each episode. Some mentioned the couple just seemed “too nice.” I must question our discomfort with watching a black man on screen who is neither aggressive nor a comedic buffoon. And then there were complaints of their black authenticity. Our spy heros were acting too “white” while wearing their “black” skin. One viewer spoke plainly about the “unrealistic” way they are placed in situations around the world where they should “stick out like a sore thumb.” Some found it ridiculous that these black bodies would be accepted as competent, multilingual, multifaceted agents exercising their agency. This I found curious, unfortunate and offensive. In the midst of this new age of post-racial rhetoric, how is it so many continue to operate under the assumption of a black monolith. Within the parameters of this logic many of my family, friends and colleagues exist as inauthentic exceptions to the black “rule.” Artists, academics and environmentalists float about like rare magical creatures. My own son who, since kindergarten has studied Mandarin, Spanish and American Sign language and just spent his thirteenth summer happily practicing a collection of Schubert’s shorter works for piano forte (a laughable description since the average number of pages for the pieces is twenty), would indeed be something of a unicorn. I mention him not in an effort to toot a parental horn but to offer an intimate example of a reality that remains hidden only because it is unwritten, rarely projected and shielded from view. The question of authenticity is a very American question because “blackness” as operationalized is a uniquely American concept/construct. This is why I’ve placed “black” in the title in

quotation marks.

Perhaps the curious failure of the Undercovers highlights our own failure to see blackness in all its diversity. More importantly it highlights the effects of an unwillingness to produce diverse representations of blackness in media with black Americans being complicit in that failure. Black people are written as pimps, players and buffoons by others and they write themselves as pimps, players and buffoons as well. Was The Undercovers really a terrible show (the ratings are fairly comparable to other shows of this type) or was it just too difficult for us to watch two brown faces speaking various languages not least of which was “proper English”? For me, these spy dramedies exist as fantasy therefore I read them as such. Fantasy and Science Fiction have long been a haven for “others” represented with dignity. In her discussion of black bodies in science fiction Sandra Jackson writes:“I long for stories about the future in which issues of difference, race/ethnicity, sex and gender, as well as colour, transcend historical and traditional coding, racializing beings and aliens from other planets and solar systems. Then the darker ones will not be predictably sinister, horrific, unpleasant to look at, predatory, and unworthy of humanity and trust in terms of engagement, or sexualized as deviously seductive, lascivious, tropes for the consumption of male desires of the exotic other.” (Jackson, Demissie, Goodwin 2009).1 The failure of this show is, for me, curious. Not the failure to produce, but the failure to consume. This seems to be a year of dangerous, radical representations which are dangerous and radical in ways we don’t expect. They proudly tug at the fraying edges of hegemonic constructs and radically present us with… a new normal. But this new normal is only new to those who’ve bought into the dominant representations of blackness or gayness or what “hot and Latin” looks like, etc. Steven and Samantha Bloom are a radical representation because they contain none of the hypersexed expected aggression that we’ve come to accept/expect as “black” television. The Blooms were written as American spies. They are read, however, as “black.”

Image Credits:

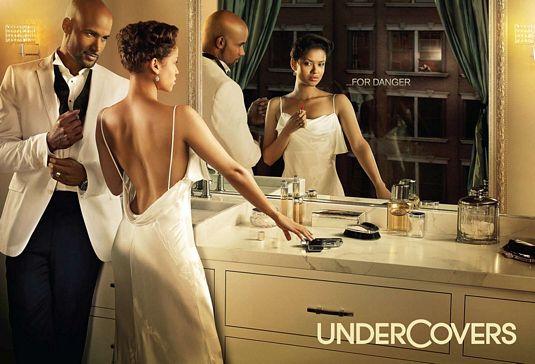

1. Publicity Shot 1

2. Moonlighting and Hart to Hart

3. Undercovers in Italy

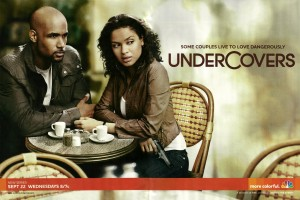

4. Publicity Shot 2

Please feel free to comment.

- 2009 Sandra Jackson The Black Body: Imagining, Writing, (Re)Reading Sandra Jackson, Fassil Demissie & Michele Goodwin (Editors) Unisa South African, Unisa Press. [↩]

Hi Camille,

Thanks for writing about this! This show’s particular failure was sort of a weather balloon for networks in terms of if America is ready for a show with two black leads. The answer? Not yet.

Your point about Othering in sci-fi and fantasy is taken and I won’t trouble you with that. As to your point about the Blooms as “radical” representations, I disagree. I think the reason they appear that way is that the parts that Raw and Kodjoe accepted were blindcasted–that is, race was not written into the script. They auditioned lots of folks for the parts and settled on those two. Blindcasting as a practice usually produces a different (maybe radical) type of representation. Grey’s Anatomy blindcasted its characters; ABC Family shows do it quite frequently.

The goal of the practice is to do what you suggest–give people of color the opportunity to play characters outside of the list of types they’ve been ascribed. So, that is good–for the actors at least. And it gives the showrunners a leg up in diversity because “look, there are black folks”! However, blindcasting also allows them a way around dealing with race–because the color of the actor in the role doesn’t matter. And, mass audiences (read: white people) do not want to deal with race unless it’s a show that is specifically about race and that doesn’t happen on network television very often. So this is the great downside to blindcasting—since the race of the characters is never considered, they are written just like any other character–which means that they are written as normatively white. So, the argument that they are “white folks dipped in chocolate” DOES actually have legs. The producers of Undercovers talked alot about how the show was not “about” race. But when you introduce two black leads into a network show (which hasn’t been done–especially on NBC–in YEARS) acknowledging some cultural specificity is important. Code switching, for example, is done throughout the African diaspora–it’s not necessarily improper talking as much as it is an acknolwedgement of sorts.

I’ll conclude by saying that it seems like your conclusion desires for these folks to be read in a more racially transcendent way because of the harmful effects of stereotypes past. However instead of creating a binary where we have to choose to see them as either Black or American, seeing the Blooms as Black and American is also a possibility. Because “American” is its own type and I’m not willing to let go of identity politics (even if it means in some instances intentionally essentializing to create difference) to accept that they are JUST that.

Hello Kristin,

Thanks for your comment. I think what’s needed here is a much deeper exploration of this show, what it reveals about “tastes” in America and what it means for the future. Your discussion of Blindcasting is interesting. I find the representations here “radical” in that the writers, even after casting, fought the urge to systematically imbue these characters with “markers” of blackness (as hegemonically defined) episode after episode. The notions of “racially transcendent” or “post-racial” are causes I can’t quite “get behind.” My call here is to see blackness in all its diversity. For example, I agree code switching takes place, but my question would be, should we assume all black families engage in the practice? And, is there only one way to engage in code switching? Or, perhaps more importantly, does not engaging in code switching make you less black? I contend here it makes these characters less “black.”

You mention essentializing. For curiosities sake, what traits would you have given these characters? What characteristics might have made them more “authentically” black for you? I find authenticity a slippery, fuzzy, concept.

Thanks again.

C

Good article, Camille.

I haven’t seen the program yet — I’ll have to catch an episode or two someplace. (Netflix, perhaps?)

Highly plausible that having an AA couple star in a show outside of the normal, stereotyped context created dissonance in audiences used to seeing blacks in “Tyler Perry-esqe” situational comedies.

Too bad.

Sherrice

I also think a discussion in the failure of this program is warranted within what Mary Beltran calls “bronzed whiteness.” I find it interesting that these roles, whether blindcasted (as Kristen suggests) or not went to little-known (at least within the mainstream) actors who cannot immediately be pinned down as black, particularly given the politics of black women’s hair.

Clearly, as you suggest, there is (and shouldn’t be) a monolithic notion of blackness, but it seems that as we argue against that, we have to undo more than a century of images that have taught white viewers what blackness is and what blackness ain’t (to paraphrase Marlon Riggs). It seems that the failure of Undercovers stems for the lead characters being “too white” to be embraced by an audience looking for a mass mediated notion of black authenticity and “too black” for viewers who dislike “color” on their TV screens. As such, it was left with an audience that, while respectable, likely didn’t cover the cost of advertising vis a vis the cost of shooting in exotic locations (assuming that the show was shot on location).

Overall, thanks for discussing this show!

Camille,

You write: “[The writers] fought the urge to systematically imbue these characters with “markers” of blackness (as hegemonically defined) episode after episode.”

But that’s the joy of blindcasting! They not once had to even consider marking them different or placing any signifiers of blackness because race was not written into the role. They wrote them JUST like they’d write a “normal” (read: white) character–which transforms diversity into merely being able to count the number of black folks on your screen making this an issue of quantity rather than quality. And, yes, cultural specificity, even as different as it would look across a variety of black households is still different from the hegemonic norm.

Responding to your code switching point, do all black families code switch? Well, if we acknowledge that we live in a state of double consciousness where we as black folks have to know at once how we are being perceived by others as well as how we are to perceive them, then yes, code switching is a necessary survival skill. Does it look the same for all of us? No. But it is present. And as racialized bodies, that is something that we might aspirationally love to transcend but materially is an impossibility. So, when I watch a show and it’s never an issue for these two black leads? Where they go to Ireland and put on an Irish brogue (never mind it’s not a part of our visual iconography that black Irish folk exist) and I’m supposed to buy that without some sort of meta conversation between these two? No way. That’s some colorblind rhetoric being deployed to displace the space of blackness (in whatever form it wants to take) with normative codes of whiteness.

Colorblindness ensures that the politics of black respectability are intact and that whiteness is the standard to which we all adhere. And, colorblind casting leads to writing decisions that follow that suit. So, it’s not so much an issue of less black or more black–it’s an issue of what’s acceptable for a mainstream audience (cause the networks don’t care if black folks watch tv). Abrams and the showrunners of Undercovers tried to overemphasize that the show wasn’t about color–who is that for? Not for a black audience who might expect some markers of difference.

Finally, yeah, I don’t like authenticity either. It’s impossible. I ask for cultural specificity–things that resonate with my (varied and different) black experience. What that looks like exactly? I don’t know. In many ways, cultural specificity is like trying to catch a shadow. I just know that two black professionals who work in an industry where they are probably the only two black professionals who’ve earned a spot there, probably would talk about race in some manner. And they don’t. Because they can’t. Because the Blooms are not allowed to be different because colorblindess says they’re just like us. And that’s a lie. And that’s why for me, the diversity of representation is actually too generous for this series. It’s actually a flattened, whitened representation.

Sherrice. Thanks so much for chiming in. I’ll have to wish you luck in finding/accessing the episodes. There seems to be a “black-out” (no pun intended) on episodes of this program. I agree wholeheartedly. It is “too bad” the plug was pulled. It was a good start to variety in representation which is much needed in the black community(ies) as well as the country as a whole.

Al, wow! Thank you for taking us further down the rabbit hole! And for the record, Marlon Riggs is so missed. I feel strongly that what we have here is the start of a very long conversation deserving of deep and nuanced attention. I am there with you on the politics of hair issue. Oddly enough, showing her with “textured” hair somehow makes her racially ambiguous, when, in a way it should ethnically ground her, but doesn’t. One thing I was struck by was how, though we can read Mbatha-Raw as ambiguous the actress which plays her sister is not which, for me, worked to reinforce Samantha’s blackness. I’d like to do more research on production cost vs. advertising revenue. This would be the easiest answer on why the show was canceled.

Ah. I see Kristen. I think you and Al would have much to discuss through the lens of Beltran and her theory of “bronzed whiteness.” With respect to code switching I think that concept needs to be expanded and fleshed out. It feels relevant but stale to me. If I am honest, I must admit to contextualizing my language contingent upon the field I find myself. I don’t live a life from office to home. It’s more like campus/home/lunch meetings/cultural visits/classroom etc. so while I understand the assertion of double consciousness to be honest, I feel much more fractured than that. My black identity is the easiest, least slippery identity to cultivate, maintain and express. It is, in some ways, my most refreshing identity. It doesn’t insist that I dress, move or speak just so (unlike my prof.ID or mother ID or wife ID). For this reason I’m at ease with Samantha and Steven as they are. Reading this show as the progeny of Hart to Hart and Moonlighting, discussions of race would have been weird. Perhaps we are asking to much? House of Payne doesn’t represent me or my experience but I’m okay with that because I know it does in fact represent someone. Can we not give this show the same consideration. This show may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but there is room on the screen (If there’s room for Snookie, there’s room for Steven and Samantha). By the way, I love your metaphor of grasping at shadows. So true.

Mrs. DeBose strikes again with disassembling the monolith of Blackness. A great conversation piece, Camille.

This may very well be the limitations of my own understanding but it seems that when one attempts to disengage the monolith, they find themselves caught in the racial paradox. That is, because Blackness is constituted by the othering whiteness in the same way whiteness has been constructed by its othering from Blackness, we fall into the conversations of “too Black”, “not Black enough”, “acting white”, “too white”, etc. I’m not sure this phenomena impacts white folks in the same manner it affects Black folks, if at all.

And, shout-out to Al for quoting Marlon Riggs’ “Black Is…Black Ain’t” and its usefulness in deconstructing. We see you!

Johnathan I really like this phrase, “they find themselves caught in the racial paradox.” I absolutely agree. I also agree this paradox is constructed and wonder what it will take for us to achieve escape velocity. We can’t wrap ourselves in “cultural armor” if we refuse to engage with media that doesn’t fit our constructed notions of blackness.

Hi Camille, this is Camille (weird…)!

Thanks for sharing this great article. As a TV lover, I am just so annoyed that this show got canceled before I could even catch a glimpse of it! They stole my right to complain and now I can only complain “in theory”. Yes…talk about the racial paradox…it really keeps you spinning and no one ever seems to agree on anything. It feel like no matter how sophisticated our language gets to describe our opinions, it’s an impossible argument. It is kind of sad actually, because it’s like you can’t win. I like being black, like seriously. I didn’t used to always feel that way (for silly reasons), but now I do. I would also be unhappy if I was a part of the invisible monolith of whiteness, so it’s like what view of race are we cheering for? It’s embedded in everything. No matter what though…when it comes down to it, I would like to see at least 2 well written MAIN characters, played by black people on GOOD TV shows more than once every 10 years. And not only on HBO or Showtime…on normal networks I can watch via the Internet without having to purchase cable! I think the media industry is lazy and scared. They need to get it together!

Good essay, Camille. I always figure being black is like being pregnant–either you are or you aren’t. The idea of having to defend one’s authenticity is ridiculous. Whatever I do is “black” because I do it. So if I choose to play the bagpipes while dancing the hula, then it’s authenic because it’s me, and if people don’t know how to process me based on whatever ignorant preconceived notions they have, that’s not my problem. So yeah, seeing a black couple playing against type would have been awesome.

That said, I totally never watched that show. :) I wanted to, but I was always at work when it was on. Bummer.

Thank your for commenting Dia and Camille. You are both, as they say, preaching to the choir. Camille, I’m right there with you in loving my self and the blackness that shapes and sometimes defines it. I am proudly who I am and because I am black how can what I do be “inauthentic?”

Dia, it is indeed a ridiculous notion. I think, for me there is no issue here. I am black and I like to snowboard. There! However, I think the solution for the greater numbers among us is a push for more diversity in representations of blackness, which I know is a real crusade for you and it is a phrase we keep repeating out loud, but it will take a brave and prolific group to continue to push, even when those that look like us tell us what we do is not real (or “real” enough for them). As my filmmaker hat begins to fit more comfortably I’m fascinated by the lens on reality it gives me. I just thought I would make some movies. I didn’t realize it would require me to become a revolutionary. ;-)