Don’t Hate The Player, Hate the (Nearly Impossible To Win) Game: Analysis of Minority Employment

Kristen Warner / The University of Alabama

Last week unveiled the new season of series premieres within the televisual landscape. The anticipatory nature of season premiere week is laden with anxieties about which new shows will succeed or fail and if the returning series will continue to tell good stories. The new fall season is also annually enmeshed in conversations about the lack of diversity both in front of and behind the camera.

Recently, the Directors Guild of America (DGA) released a report indicating that of the 2600 episodes analyzed from more than 170 scripted television programs produced in the 2010-2011 season, 77% were directed by white males; 11% by white females; 11% by minority males and 1% by minority females.

The numbers do not fare better in writing or acting. According to the Writers Guild of America (WGA) report women remain underrepresented by factors of 2 to 1 among television writers, while minority writers maintain their consistent underrepresentation by factors of 3 to 1 among television writers. In acting, the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) reports that in 2008, whites dominated the share of television and film roles by 70.7%, leaving African-Americans 14.8%, Latinos 6.7%, Asians 3.4%, Native Americans .30%, and unknown 4.1% with what remained.

What these numbers translate to is more than Hollywood having trouble finding good people to employ; no, these numbers speak to Hollywood’s willful disregard for accepting difference into its logics system. As an industry comprised by the sum of its parts, Hollywood is made up of individuals with paradigms and experiences that more times than not and negligently more than maliciously, ignore that people other than those who look like them exist and are hirable. Moreover, what’s more peculiar is that the burden of proof rests with those seeking work because, of course, Hollywood cannot legally discriminate on the basis of sex, race, religion, or sexuality. But, if the television industry is a system that churns laborers out through apprenticeship and internship and if those positions are nearly always filled by whites (particularly white men), then the institution itself has designed a strategy of indirect exclusion that prohibits minorities and women from even being able to access the opportunities.

What’s more is that the numbers released by the various guilds are ultimately disseminated to shame the industry and its members who participate in this employment exclusion. And for the duration of the fall season’s media coverage, mea culpas are issued and the citizens of Hollywood take a beating for their disinterest in improving the diversity of their industry. However, once the news cycle ends, it is back to business as usual.

This is not news nor is it the crux of this column. Instead, I want to explore some of the strategies that guilds and its underrepresented membership deploy to circumvent these institutionalized barriers. What’s fascinating about these strategies is the way that racialized difference is displaced by the neutrality of the post-racial era—thereby playing into the very same logics that allow them to be excluded in the first place.

1. As I sat down to watch the CW’s Ringer series premiere, the first scene is set in an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. The intertitles reveal that these characters live in Rock Springs, Wyoming. And then I am introduced to the main character’s sponsor, played by Mike Colter, a black actor. Colter portrays a professor at the local university with a soft spot for his sponsee. The first thing that I did when I put all of these facts together was visit Twitter and write, “There’s a black man in Rock Springs, Wyoming. Alert the media.” It is not that I think it impossible for a black man to live in Wyoming. Indeed, as an academic, the instability of the job market often means that a job is a job—even if it takes you to Rock Springs, Wyoming. However, the probability that within the town of Rock Springs, the man who just happens to be the lead character’s sponsor is a black man is slim.

Of course, Ringer would argue that my noticing his skin color misses the point. However, because the character functions as the literal embodiment of visual difference rather than a qualitatively representative one, I argue that race is a major point. Specifically, I contend that the part was blindcasted, that is, the part was written without specifying race into the script.

Underpinned by neo-liberal race logic, colorblind casting deploys a universal, “we are all the same” rhetoric that superficially fixes the issue of racial representation in television and film. Blindcasting becomes a useful tool for industrial practitioners because it allows them to avoid explicitly writing race into the script while ensuring “equal opportunity” for actors of diverse backgrounds to audition for and even be cast. Yet this practice only corrects the issue of racial diversity through visibly sprinkling television with color. Rather than actively pursuing diversity by hiring minority writers and/or showrunners to create culturally specific roles for people of color that could, for example, explain the exceptionalism and perhaps the oddness of a black man in Wyoming, the television industry prefers to make roles racially normative, where the norm is “whiteness.” Thus, blindcasting forces minority actors who desire gainful employment to input their cultural difference and output a standardized form of whiteness.

What’s more is that this normative whiteness is so accepted and common sense that me asking, “Why is this black man in Wyoming?” makes me the oddity who brings up race where it is not an issue. Yet, Colter’s existence in that location functions as Stuart Hall describes, “a matter out of place” thus acknowledging and understanding how he got there is an important component in understanding the show’s larger assumptions about the role of race in its series.

2. The last strategy deployed by underrepresented groups to circumvent the industrial barriers to employment is through the self-fashioning of the racially ambiguous actor. While discourse concerning the new fall season promotes shows that feature racially identifiable minority characters, more and more often, television is featuring racially ambiguous actors. Recalling the earlier statistic from SAG, racially unknown actors accounted for 4.1% of all roles in 2008. The category racially unknown is defined by the fact that these actors did not select a racial category on the surveys SAG sends to identify the racial makeup of its membership. According to interviews with guild representatives, the members opt not to self-select because they fear that racially identifying themselves will relegate them only to the roles that allow that racialized group.

Implicit in this logic is that these individuals believe they can racially pass as something else. So, Jessica Szohr’s biracial ethnicity remains questionable in Gossip Girl unless you read her IMDb profile. Similarly, Jessica Parker Kennedy’s racial ethnicity is ambiguous allowing her to pass as just one of the girls in the witch coven in Secret Circle—even though there is something “not quite white” about that girl.

However, it is not just questionable race at play with this strategy. Blair Redford’s ambiguous look allows him to be Latino for ABC Family’s Switched at Birth and Native American for ABC Family’s The Lying Game. While this clever strategy certainly allows for employment because it asserts that the actor has a look that could be interpreted through a variety of “types,” it privileges (sometimes racist) assumptions about the look of a given racial group. In addition, it amplifies colorblindness’s power by not only making race something “unseen” but by overtly detaching racialized bodies from the socio-historical contexts they emerge.

In the end what all this means is that cultural specificity—through storytelling and through casting—is afar off. More practically this means that when there’s a random black man in North Dakota during next year’s fall season? You’ll know why.

Image Credits:

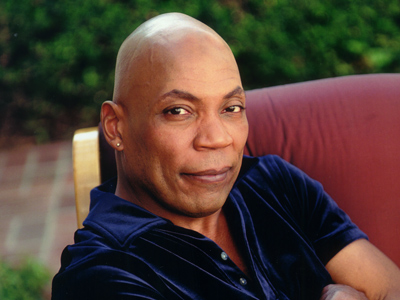

1. Paris Barclay

2. Mike Colter

3. Gossip Girl; The Lying Game; The Secret Circle

Please feel free to comment.

- Clockwise Jessica Szohr for Gossip Girl; Blair Redford for The Lying Game; Jessica Parker Kennedy for The Secret Circle. [↩]

The actor who plays Bridget’s sponsor on Ringer is Mike Colter, not D.B. Woodside.

Keith,

You are so right. I clearly am participating in the same confusion as the folks who confused Idris Elba with Akon at the Emmys two weeks ago. This is being remedied stat. Thanks for pointing my egregious snafu.

I promise I don’t think we all look alike.

Another fantastic article Kristen. This notion of blindcasting is interesting as we look at bodies of color on television as well which bodies of color are cast (getting into racially ambiguous territory). This post-racial rhetoric has us culturally in a bind because we want to assert that race no longer matters (even though it does and the ones who want it not to exist are those who will benefit from no more “preferential treatment” for brown and black people) and that, as you say, “we are all the same” which robs people of color of any cultural specificity, harkening back to the days of Julia and I, Spy, but then if we had Good Times 2.0, that would also be problematic.

I think the problem can be remedied, as you implictly say, by having more bodies of color behind the scenes directing and writing. There is a much greater opportunity for diverse racialized bodies if we have people of color attempting to write and represent their stories.

This is a great essay, Kristen, and your points about the fallacies of colorblind casting are right on target. The issues you raise here leave me wondering about what can be done to dismantle the assumption that colorblindness is the answer to problems of racial representation in this day and age. We seem to assume that the inclusion of more minority writers and directors would be a direct challenge to “colorblindness as solution,” but I wonder whether that’s enough. It seems that we’re at a point where we need to focus on basics, such as questioning the notion that colorblindness is inherently a good thing. I’m not sure how to go about this, but I do think that your simple questioning of the existence of a black man in Rock Springs, Wyoming is a good start.

Nice piece! I’m wondering whether the opportunities of seriality might allow blindcasting to function both to accomplish its progressive goal (to open up roles to qualified actors regardless of race) and overcome its regressive tendencies (treating every role as normatively white). Because serial narratives (ideally) allow characters to develop & deepen over time, a blindcasted role might become more culturally specific & grounded through the collaboration between actor & producers as the character develops. Obviously having more people of color behind-the-scenes is crucial for this, but the fact that a serialized character typically emerges slowly over the course of a series seems like an opportunity to counter the negative assumptions of such initial casting practices.

Thank you for the provocative essay. I really appreciate the important topics addressed here, the new trends for casting ethnically and racially ambiguous actors and for colorblind casting that often is left unexplained within series narratives. I think it’s important for us as television scholars to also keep an eye on what doesn’t make it to the screen through these dynamics. While mixed-race and other ethnically ambiguous actors today may find that they are getting to audition for more roles, the end result is that they are being cast instead of darker skinned actors of color. It’s also notable that while mixed-race actors are getting roles right and left (and as a mixed-race gal myself, I know and love them all), we’re not seeing mixed-race characters and families, or mixed-race subjectivity on the screen in these instances. In my personal and professional opinion, the new colorblind ethos we’re seeing so much in television in fact refuses to acknowledge the history and realities that we’re still living with.

Thanks everyone for the comments! I have spent a lot of time with this stuff in my head so it’s good to get some feedback, lol.

@Al: Right, a Good Times 2.0 would be problematic. And, for all intents and purposes we have that with Tyler Perry’s shows on TBS. The only difference is the showrunner is Perry and not a white dude like Norman Lear. But the same conventions apply: a pluralist universe that is “separate but equal” from the white world they parallel. Yet I’m not quite sure that throwing Perry’s shows out completely is the answer either because, well, his work does have resonating power in terms of affect.

@Gates: Yes, dismantling colorblindness would be a great start to all this. It is difficult though because embedded in the logic of colorblindness is white privilege and naming normative whiteness in a way that makes folks very uncomfortable. Colorblindness is so successful because by saying we are all the same it theoretically gives everyone the same opportunity, obscuring the ways that systemic racism contradict that logic. The threat of taking that away is just not feasible unless those in positions of power lay claim to what they possess. sighs. So the random ass black man in Wyoming just continues because where else would he be?

@Jason: Yes, your point makes good theoretical and common sense. The longer project I have deals with Grey’s Anatomy and the way its showrunner and the network publicized the shows blindcasting innovation that yielded a multiculti cast. Rhimes put the cast members in interracial relationships but according to her it only happened because “that’s what she had planned for the characters.” It would make sense like you said that as the actors subsume themselves into these roles, specificity would emerge. But actually the opposite happens because if there is not specificity written into the roles then many times the actors accidentally fall into tropes. So, Bailey (Chandra Wilson) ends up playing an asexual mammy for the first three seasons of the show–not on purpose but because there wasn’t a consideration in the writing room that said, “wait, this is a full figured black woman who is married but whose husband we never meet and she is taking care of all these white residents and that will play wrong because there is historical precedent.” And so it was. Same with Burke as a “super spade.” In short, seriality SHOULD be a way to work through it but if blindcasting is the decided trajectory it’s hard to expand from there.

@Mary:Thanks for your comment! I had footnotes that shouted out your Mixed Race collection, lol. And you are so right about the pitfalls of colorblindness (the entire concept is one giant, gaping hole. Yes, mixed race folks are by and large increasing in turns of gaining roles and still trying to play the game without identifying themselves for their actors guilds. As I’ve understood it, most of the time, they believe more than the casting directors that they can pass for a multitude of identities. And many times, they can’t. But when they can be just different enough in look to serve as the visual other, that’s the sweet spot.

In terms of the lack of mixed race subjectivity: The most egregious example I’ve watched recently was on ABC Family’s Switched at Birth. Constance Marie plays a Latino who had a baby with a mixed ethnicity man (he’s French; he’s Spanish; and some other stuff) and the part that you have to suspend all disbelief in order to buy the narrative is that she WITHOUT question believed that she birthed this strawberry blonde, fair skinned, blue eye baby.Race never comes up with this show (and it makes me so angry) so it’s not surprising but still, the lived experiences of a Latina are displaced in the narrative even as the stereotypes about her racial identity emerge without critique.

Thanks again for illuminating what is such an obvious divide between the lived and visible realities of most Americans and their lack of representation through blindcasting.

Not sure what I have to contribute to the discussion, but will say that in other countries, since much of culture is tied to public funding, there is some government control over who gets represented. Recently, I have been surprised by the diversity of casts in other nations’ TV and movies (such as the Misfits, Little Mosque on the Prairie, etc…) especially those which are not necessarily known for their multiculturalism. In the UK what is also striking is how a majority of shows also factor class and accents into their culture, which is something that US media seems to eradicate with their use of either a) the “standard American dialect” or b) foreign talent pasting on thick regional accents, as in True Blood, or the Wire.

The answer, in Canada was to actually legislate the representation of diversity, which is somewhat successful (but certainly doesn’t solve the larger problem). Now whether these films and TV shows are actually seen on screens is another story, but this emphasis on local details and through national, regional and local funding structures seems to create a slightly less homogenous vision by actually focusing on the specific aspects of regions.

All of which is to say that I’m not sure that letting the market decide (which seems to be the current strategy) is anywhere close to solving the problem.

@Colin, I agree with your comments here regarding UK TV. I’ve engaged with the shows you’ve mentioned and was fascinated by the inclusion of class via accents. I’m currently watching LUTHER and appreciating every moment.

@Kristin you know I’m with you on the useless and, in many ways, damaging colorblind (or its cousin post racial) rhetoric. There is an aspect of this, however, that I think is being conflated with other issues. Your comment here:

“Thus, blindcasting forces minority actors who desire gainful employment to input their cultural difference and output a standardized form of whiteness. ”

I think this notion of “standardized form of whiteness” deserves a broader conversation, and let me contextualize by saying I was born and raised in a valley in Southern California. I’m certain it colored my perspective, but we’ll bracket that. Anyhow, when I here this phrase I question what is meant. What do we “read” as white on TV? Well educated? Affluent? Stable? Married? Comfortable? At peace? Is it all or some or… I’m sure you understand what I mean. I’m angry, or perhaps jealous in a defiant way that the markers of a peaceful and well adjusted existence belong to whiteness. Who made this rule? While blindcasting may not be the answer perhaps the odds in this game are far worse than your title implies. If a black actor plays a role steeped in urban conflict he’s too black to play anything else. If he plays a role where he’s a professor living in Kansas, Wyoming or Iowa he’s unbelievable. Televisual representations of people of color are so narrow, rigid and constricting it’s no wonder all our actors don’t perish from the pressure.

Totally unrelated to the above comment I was reminded, while reading this, of the long tradition of self publishing in communities of color for this very reason. The willful refusal to competently represent. I’m not a fan of Tyler Perry but I certainly wish we had a few more like him. Perhaps one that does fantasy films and another that does horror. One girl does Sci Fi while this other guy does musicals… Ahhhh… I can dream.

Hey Camille,

Thanks for your comment! When I say standardized form of whiteness, I mean the very definition of whiteness as this ex-nominated, unmarked, uninterrogated, empty signifier space where difference is relegated to Others and never has to identify itself or be self-aware. I mean whiteness in the sense of it always having the privilege of not naming itself and taking advantage of its invisibility. I mean whiteness as in the taken for granted attitude that it is the norm, the standard by which all of us who wish to be successful must work toward and perform to the best of our abilities. Yeah, I too am jealous of the way it’s been marked off!

I don’t think it’s about occupation or affluence or comfort. Black folks have been docs, lawyers, judges, cops, etc. What it is about is acknowledging that we ARE different; that we are seen different; that we are (or should be if we’re honest) and have to be self-aware of our performance because we don’t get to name ourselves in that system of representation. So, when whites name us JUST as they are, discounting the different shared experiences and histories and contexts, they are diminishing difference and stamping us as the same as them.

There is no visual iconography that goes to black men in Wyoming or North Dakota. That is not apart of our collection of signifiers. It doesn’t mean that there aren’t real folks there (I’m sure there are) but in representation it is matter out of place. And to not explain it–because dammit, if I were the only negress in North Dakota I would holler to the rooftops that I was the only one and tell everybody how nervous I was–neglects that out of placeness.

@Kristin:

“And to not explain it–because dammit, if I were the only negress in North Dakota I would holler to the rooftops that I was the only one and tell everybody how nervous I was–neglects that out of placeness.”

Hahahaha!! I won’t lie. I’m going through a faculty appointment search now and regardless of being a valley girl, there are just some states…. Well. There are some states that, as you say, make me nervous. If not for myself, then for my husband and the little brown boys we bring in tow.

You ask much of TV and I salute you. Hell. Somebody needs to hold some feet to the fire.

Pingback: Girls Like Giants Presents: Our 2011 Preferences (Chelsea B.) « girls like giants