Acrophobia: IRT: Deadliest Roads and the Pitfalls of Neoliberal Globalization

Jacob Hustedt / FLOW Staff

In IRT: Deadliest Roads, the History Channel’s 2010 spin-off of their popular Ice Road Truckers series, three “all-star” members of the original Ice Road Truckers crew are sent to Northern India and tasked with hauling freight from the densely populated streets of Delhi up into the Himalayas where supplies are needed for the construction of a hydroelectric plant. As the season continues, the truckers’ skills are used for a variety of missions in Delhi, Shimla, and the lower Himalayas, ranging from road construction projects to, in the big series finale, flood relief efforts. The protagonists of Deadliest Roads are each seasoned veterans of North American off-road trucking and come to India to face the challenge of “driving on the deadliest roads on earth.” In IRTDR, the semi-driver, with his historical ties to NAFTA disputes and American global trade, becomes an uncanny representative body for North American transnational commerce. In the early episodes of the series, the three central protagonists— Rick Yemm, Dave Redmonn, and Lisa Kelly— are each assigned a truck and a truck wallah who will act as interlocutor, spotter, translator, and increasingly, as the series progresses, quiet antagonist to the fiercely and sometimes violent neoliberal independence of the North Americans. The surface problematics of this colonial dynamic are obvious and tired. At a fundamental level, the show is, indeed, overtly xenophobic, operates at the level of poverty tourism, and other than the oft-repeated statistics on India’s vehicular deaths, offers little to no information on its supposed area of study. This is an old tradition, a worn-out insult— the Western colonizer with his native informant— that despite its consistent rebuke in politics and academia continues to rear its ugly head. This manufactured collision of cultures, however, reveals how the politics of old colonialism continue to reverberate in new ways against the transnational tides of neoliberal capitalism. In IRTDR, the chaos of transnational identities and global commerce convex around the anxiety laden twists and turns of the Indian Road. Simultaneously prone to rock slides and flash floods, winding up seemingly insurmountable Himalayan ridges, descending just as quickly into bottomless gorges and cavernous valleys, rolling through crowded cities teeming with people, and through endless stretches of rugged rural countryside, these roads signify the inscrutable contradictions of India’s tenuous position as a growing global power, its soaring GDP, and its widening gap between the rich and the poor.

On the surface, still, IRT: Deadliest Roads is an excruciatingly boring viewing experience. Repetitive and dull, stretching on for an unseemly forty-five minutes per episode, one might be inclined to credit the producers with purposefully inciting an Antonioni-esque sense of highway hypnosis. Consistently, however, this boredom, the tedium of tired tropes, and the banality of old colonial rhythms is interrupted throughout the series by the one pleasure that IRTDR offers— the thrill of acrophobia, the fear of heights. As our heroes veer onwards and upwards, often on the very same roadways episode after episode, the daze of untold miles of rugged terrain and traffic jams is broken only by the impending doom of dubiously-named roadway hazards like the “Freefall Freeway” and “Pile of Corpses Pass.” As the trucks veer closer and closer to the invisible ledges of these dilapidated highways, the monotony of their journey is often broken by the viewer’s sudden realization that these truckers are indeed traveling very, very high on very, very dangerous roads. The response is reflexive— an audible gasp or the sudden clenching of a sofa cushion— but it is through these bodily sensations that IRTDR anchors its viewers to the specificity of its setting. As the truckers peer over the edges of these cliffs, we feel their reality; we feel the rollercoaster excitement of a body in freefall.

If the visceral stimulation of acrophobia is the central pleasure in IRTDR, my interest here is to discuss how IRTDR invites us to read these bodily sensations against the backdrop of neoliberal globalization, as epitomized so handily by the figure of the off-road trucker. When truck driver Lisa, stranded on a mountaintop early in the series confides to Tashi Chombel, her truck wallah, “I’ve never been so scared in all my life,” she articulates much more than a physical fear of falling. The stakes are higher than that. These truckers have wagered a bet that American individuality, ingenuity, and can-do technical know-how are credentials enough to navigate the steep inclines of expanding Indian commerce and industrial infrastructure. They are straddling with twelve wheels the deleterious divide between Indian culture and market culture and insist that Americanism alone is enough to bridge this gap. This is, essentially, the neoliberal gambit— namely, that through private effort and Western liberalism, global cultures can indeed be transformed into market cultures.

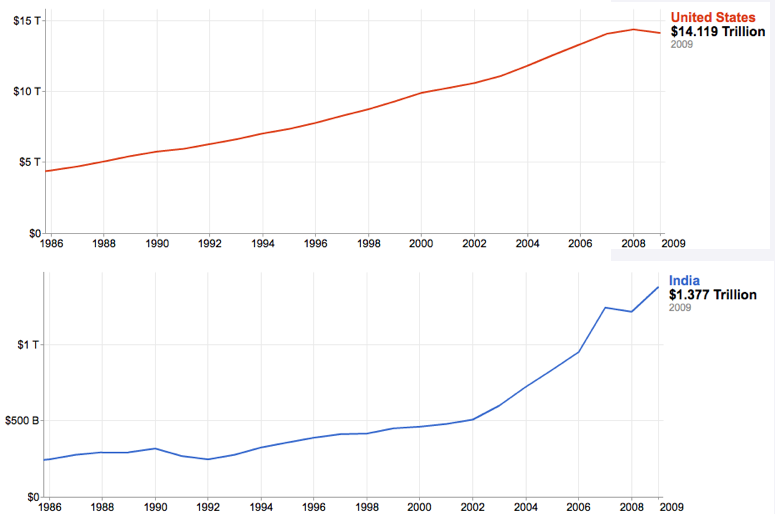

As an organizing motif, the acrophobic North American trucker at the edge of a cliff in a foreign landscape afraid of falling pithily encapsulates the uncertainty and anxiety of the US’s current economic position in comparison to the rapidly industrializing economy of India. Recent economic events stemming from the 2008 economic collapse have raised serious questions about the state of the US manufacturing sector, bringing analysts to question whether the United States still has the industrial infrastructure to regain the sharp declines in GDP felt after the recent global recession1. Meanwhile, India and other members of developing BRIC nations have seen unprecedented growth in their GDPs, with India predicting over 8% annual growth over the next five years and signaling for some a coming sea change in global markets2. Putting aside the unanswerable questions of whether or not US neoliberal capitalism has run its course, it seems nonetheless prudent to be vigilant about how neoliberalism will continue to manifest itself in the developing economies of Latin America and Asia, as private Western capital seeps into the more affordable crevices of these developing markets. The stalwart American truck driver, then, is in a perilous position indeed. As he maneuvers his way along the desolate ridges of an economic mountain that may have already peaked, it sure seems a long, long way to fall.

What gradually becomes disturbing by the end of all 450 minutes of IRTDR is the way in which Lisa, Dave, and Rick choose to cope with their acrophobia. Slowly, the truckers begin to realize that they will not be able to tackle the challenges of the Indian roadway themselves. “We’ve got to stick together to get out of here,” Dave declares after a particularly stressful day on the road. The alliances that the North American truckers eventually form, however, are not between themselves and their demonstrably more knowledgeable Indian counterparts, but rather between each other. As their bonds strengthen, their partnership is increasingly posited along racial lines. In perhaps the most unsettling scene in the series, Rick and Dave corner a particularly aggressive Indian driver with their trucks and attack him both verbally and physically for “not knowing how to drive.” The scene is hard to watch as Dave and Rick work together, cackling over their walkie talkies, as the man driving the much smaller vehicle tries to slow down and get out of the large truck’s way. The fun seems to be in the chase for these two men and after trapping their prey, they gang up on him, yelling in an angry, expletive filled rant. “I’m getting sick of these motherfuckers,” Dave yells as his truck wallah looks on, visibly shaken. “That guy took the rap for every fucker that pissed me off,” Rick concedes. The targeted violence of this encounter cements the increasingly white supremacist rhetoric of Rick, Dave, and Lisa’s union. “Don’t make one truck driver mad, because they will all gang up on you,” Lisa declares.

This deeply troubling and overtly racist turn of events in the series is glossed over, however, by IRTDR’s surface appeal to a more accessibly white and Western progressive politic— feminism. As the road rage towards Indian drivers continues unchecked, Lisa— IRTDR’s only female participant— begins to emerge as the strongest and most dedicated of the North American truckers. Initially presented as the underdog because of her gender, Lisa gains the respect of her fellow truck drivers and presumably the at-home audience through her perseverance in the face of sexism. Not only is Lisa presented as a “woman in a man’s profession,” but also as a woman alone in a sexist and backwards country. The crowds that gather in rural villages and traffic jams to witness the spectacle of a female truck driver are never depicted simply as curious on-lookers. In IRTDR, rather, congregations of Indians are always mobs and always on the verge of rioting. As Lisa continues undeterred, she is marked as a survivor and a fighter in face of adversity. She “gets the hang of this India thing,” and by the series’ final episode, she marks her ascendancy by firing her truck wallah and completing her final mission by herself, even after her male compatriots turn back because it is too dangerous.

Lisa Duggan, Jasbir Puar, and others have demonstrated how the Western export of neoliberalism has continually utilized Western identity politics as a progressive mask for the more insidious aspects of the neoliberal enterprise. IRTDR makes a vain attempt to disavow its blatant white supremacy through a brief, stuttering appeal to feminism. As IRTDR stammers on, however, it does a better job enunciating the inefficacy of its own enterprise; namely, that white North American neoliberal capital copes with its economic insecurity through a reliance on internal political homogeneity rather than by building coalitions across differing economic and cultural ideologies. This arrogance rests too often on the manufactured laurels of Western civil liberties and social progressiveness. IRTDR reveals that this is a shoddily constructed perch that simply will not hold the weight of the heterogeneity of globalization, and even in its own denial of this perilous position, it can’t help but remind us that the edge is close and there is danger of falling.

Image Credits:

1. Shandeh.com

2.

I really like this article, it’s fascinating. I think this piece exemplifies some of the theory in Barry Brummett’s Rhetorical Dimensions of Popular Culture.

I think this was a fascinating article. You manage to pull together an analysis that I wouldn’t have thought would work, though somehow you made it flow smoothly. It’s so important to make interventions wherever possible in these pop-cultural productions, to locate the historical legacies and current conditions of racism and ethnocentrism.

Thank you for this article. Unfortunately, IRT, India is followed by IRT, Bolivia, Peru. Adding Hugh to the mix doubles down on the colonialism, racism, and ugly American( Canadian) jingoism. This is embarrassing. Oh for an Anthony Bourdain-like personality to celebrate the triumphs of the local population over the natural challenges of the landscape, appreciate the incredible gorgeous topography and the incredible engineering feats to even create these roads, and celebrate the culture of the nation hosting these truckers.