Strange Steeples

Paul Gansky / FLOW Co-Managing Editor

There are few images of communications infrastructures as chimerical and reverberant as that of Radio Keith Orpheum. The sight of the radio tower that appeared before the studio’s many productions starting in 1929 made an indelible impression. What embedded itself was that burst of Morse code tapping out “An RKO Radio Picture.” Just as impressive were the fantastic splinters of lighting that bounded off into space from the very zenith of the tower as it stood atop the spinning earth. Like many Hollywood logos, RKO’s symbol left little doubt as to the studio’s dominance over nature, culture and technology – a paragon of progress reaching with supreme confidence into the great beyond.

Making the RKO tower truly sublime, though, were the deeply unsettling thoughts it produced. Where were those big volts of lighting heading? Where was their end? And who was the lonely radio operator stationed at the icy cap of the world, who kept sending messages into the firmament? For me, radio was, and still is, shaded in an exceptional kind of melancholy, since it was an activity I strictly practiced between headphones within the privacy of a closed bedroom, while everyone else slept. Switch on the receiver and let your eyes jump with the glowing nuclear needles as your head erupts in midnight static. A total immersion in apparitions.

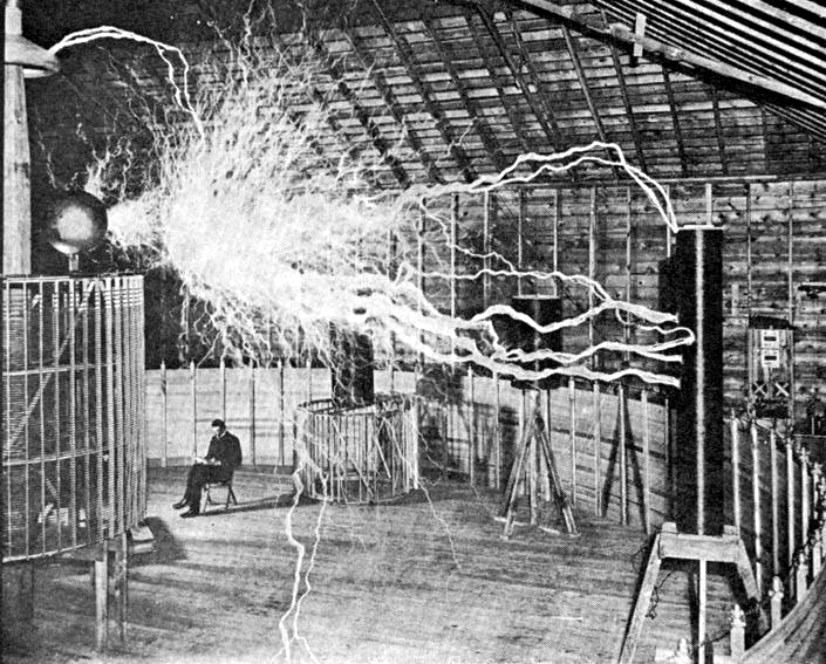

It is no small coincidence that my bedroom window framed the radio towers of the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) stippled atop Cheyenne Mountain, their anti-aircraft lights humming on and off like hot poppy seeds throughout the night. I wondered about the group of military contractors who clambered up onto the mountain circa 1967, and erected those electrified spines in all that wind and rock and sheer elevation. Did they thrum with exhilaration at the vantage they had reached? Or did they realize how ephemeral their efforts might prove to be when they looked down the mountain towards the long-vacant base for Nikola Tesla’s tower? One of the tallest turn-of-the-century structures near the Rocky Mountains, the inventor’s two-hundred-foot monolith housed a massive electric amplifier, and would have rested between my bedroom window and NORAD. It also served as the key inspiration for RKO’s iconic transmitter.1

Even the most impressive technology can simply evaporate. Tesla’s tower was disassembled after 1900, the original RKO logo ceased its beep and thunderbolt in 1958, and NORAD was officially decommissioned in 2006, although its towers still flicker each evening above an emptied grid of operations, suspended on springs under a mountain.2 These transmitters, always seen at a distance, as a remnant, or as a brief prelude before a film begins, share what Anna McCarthy and Alexander Russo have respectively recognized as the slippery nature of broadcasting elements. Experienced as “site-specific” – the tower at the end of the street, near the nail salon – such apparatuses are simultaneously a part of the “ethereal, unlocatable physics of the electromagnetic spectrum.”3 Unlike RKO’s arm to the heavens, which visually radiates kinked waves of communication, it is usually quite difficult to tell by eyesight alone if a tower is even turned on, much less the particulars of its transmissions. Neither entirely here nor there, as Lisa Parks has noted previously in Flow, these infrastructural components have been further camouflaged, or shunted to less visible and desirable real estate under pressure from various state and community organizations – in the process concealing their workings. Parks consequently calls for renewed awareness of the relationships between users, these objects and systems, and the cultural and geographical environments they occupy.

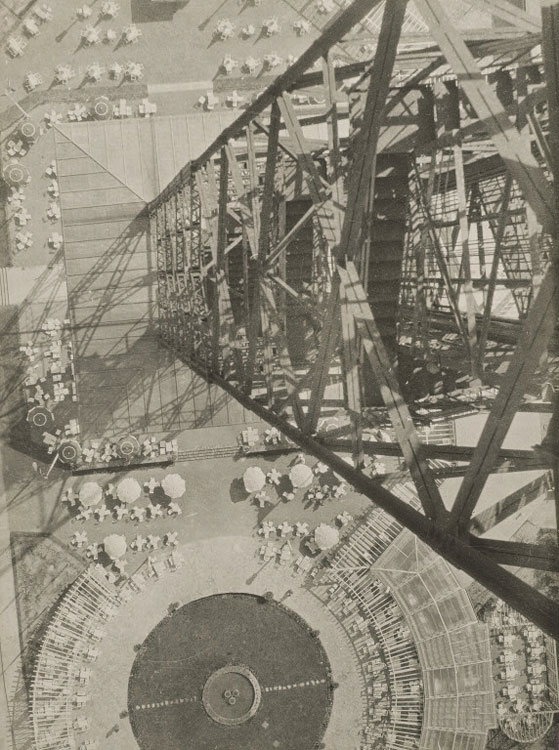

Over the past century, in fact, multimedia efforts have regularly attempted to register the effects of radio networks upon our everyday rhythms. Yet, in large part, they appear less invested in educating us about how these systems actually function, and more interested in measuring a tremendous sense of separation and ambiguity, even as the signals circulating through this architecture gradually support our every activity. Few follow the example set by László Moholy-Nagy’s photograph, Radio Tower Berlin (1928), which renders Germany’s first site of television transmissions as an astonishing achievement in mechanical control. Here, the tower facilitates a chance to survey not the sky above, but the advancing precision, geometry, and sterility of human creation below – a curious celebration of gravity not often repeated. These structures are instead seldom viewed from the top, more often peeking through the evening from indefinable coordinates.

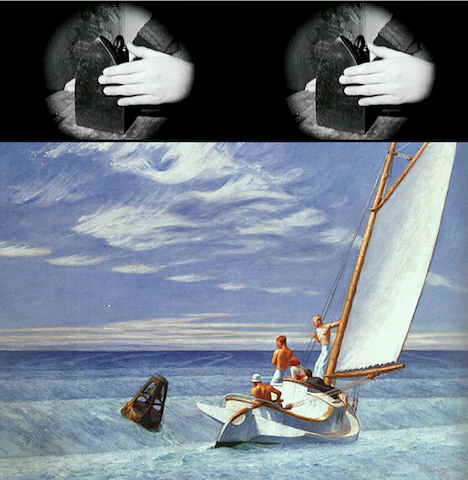

Complementing the transmitters of RKO, NORAD, and Tesla are those marooned towers in unremitting wastelands that appear in everything from Play Misty for Me (1971) to The Thin Blue Line (1988) and Boys Don’t Cry (1999). Equally imperious and inaccessible is the broadcasting antenna that monitors a young Guy Maddin from a lighthouse in Brand Upon the Brain! (2007). Even Edward Hopper, exemplar of isolated spaces and encroaching darkness, as Alexander Nemerov argues, gestures towards the recondite nature of radio in Ground Swell (1939), an ocean painting of three figures in a catboat listening intently to a bell buoy-cum-transmitter – a mystery in broad daylight – surprisingly reflective of the contemporary disconnect between radio architecture and the medium’s use through seemingly unrelated devices like computers.4

Personal radio sets do not evince nearly the same reaction. Crystal units, Bakelite readymades and boomboxes are cherished, or at least known, objects, decorating tool shelves in mechanics’ garages, kitchens, offices, and car dashboards. They are also easily thrown away, broken or simply outdated, their disposal allowing for possible recuperation and re-appropriation which makes their technological and emotional importance resonate.

Radio towers, however, remain undomesticated, daunting in their complexity, size, and military or corporate ownership, things not readily recycled.

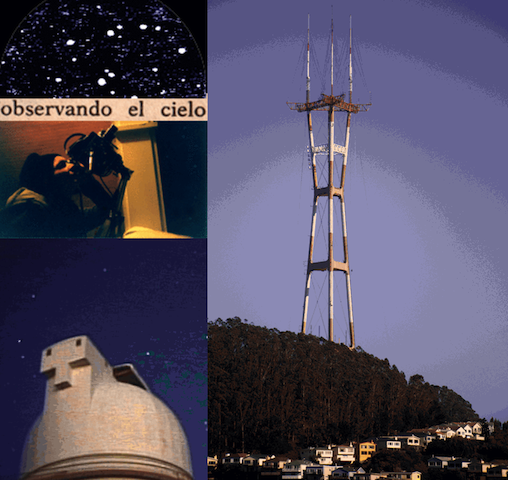

Inscrutable, unreachable and immaterial, these spires direct our eyes towards infinity and oblivion. In Jeanne Liotta’s Sutro (2009), the colossal Sutro Tower in San Francisco is glimpsed from afar through hiccupping imagery that recalls a television’s roll bar and busts the structure into bits of light. Watching the film, it is difficult to believe nearby residents would have ever believed that Sutro blighted the skyline. Perhaps they fell asleep before the edifice turned inside out and floated into the evening over their roofs like a pulsing vein. The tower seems so insubstantial, a sculpture cut from atmosphere that with each passing moment becomes less discernible, but nevertheless remains unextinguished.

Liotta’s Observando el Cielo (2007) goes a step further. Sound entwines with image to subtly suggest leapfrogging antennas; each tower catching ruptured slivers of songs, voices and very low frequency whistlers, which Tesla once sent squirming through the ground near NORAD; each tower gazing lidlessly to the planets wheeling above, a startling juxtaposition of self-absorbed electronic constellations operating independent of a profoundly indifferent universe.5 Staggering in their evocative expansiveness, these examples suggests that networks – like the earth – remain incompletely experienced, making each tower, for all their palpable height and materiality, highly elusive and fragmentary objects.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4qoymGCDYzU[/youtube]

Representations of similarly aloof disc jockeys and listeners are so common as to constitute a subgenre of alienation.6 Less represented are the experiences of those individuals who actually construct and maintain these infrastructures, often across cultural and national borders and incredibly uninhabited terrain – with the left-field exception of Glen Campbell’s warbling, morose “Wichita Lineman,” who searches for “overloads” across desolate stretches of a network and hears his loved one “singin’ in the wires.” Like the poles the repairman scales, the song is unmoored from a definite place – alluding equally to the penumbra of Wichita, Kansas, the scalded sheet of Wichita Falls, Texas, or several potential Wichita counties. Yet Campbell, crooning in 1969 before the widespread advent of wireless telephony, can at least affix his heartache to a tangible material – those damned whining cables and lines – a kind of palpability nonexistent for the radio towers of NORAD.

Perhaps a sense of the coldly remote nature of this technological latticework guided Verizon’s recent facelift into the caring communications juggernaut that allows its users to “Rule the Air.” Replete with dazzling antennas erupting from nearby newspapers stands and parking garages, Verizon’s commercials promise that the “most powerful transmitter is you,” neatly eliding any human construction or maintenance, or the vast diversity in electronic signals and towers. With strategic bits of jargon, they instead transform the end user into the network itself. Their new logo, of course, echoes RKO’s, right down to the placement of a soaring tower at the end of the earth. Verizon lacks the former design’s capacity for cosmic dislocation, though, with a centralized world stamped in a rational longitudinal grid, the surrounding space devoid even of a moon.

And yet, standing near to any one of these towers, or even glancing at them from your bedroom window, there is neither a transformative melding of humanity and machinery, nor much clarification about their workings. And although station engineers, like Maholy-Nagy, once relished scrambling up a tower for the vertiginous panorama, and prized the resulting electrical burns on their hands, after the late 1960s most of them now rely upon expensive, certified tower climbers who check everything from guy wire tension and rusted support arms to flailing coaxial cables.7 It is additionally unusual to find even the most remote tower unadorned with barbed wire fencing, surveillance cameras and enclosures for exposed hardware. Deterring terrorists and copper thieves, such security further renders these structures as black boxes, legible only to a few trained and approved specialists.8 What once registered as workable and imminently understandable now appears completely supernatural. In their capacity to baffle and enchant, these towers attain a perfect kind of abstraction, enigmas that can be can quietly managed for a general populace who finds their jumper cables arousing a low and wonderful sense of panic.

An exception is a single fifty-five-foot transmitter and receiver on Utah’s Wendover Airfield, deemed “Leftover Field,” by radio star Bob Hope, where the crew of the Enola Gay trained for their visit to Hiroshima, and their mercury B-29 bomber was slipped its payload. Built by artist Deborah Stratman in 2002-2003 at the Center for Land Use Interpretation’s site on the abandoned military zone, her wind-powered radio tower canvasses several frequencies in the nearby border town of Wendover, from casino security channels and fast food drive-thrus to Citizens Band and FM.9 Providing a rare opportunity for immediate interaction with a tower and free airwave access while also functioning as an artistic gesture, Stratman’s piece unveils the surrounding desert as a thickly populated electric force field, and demonstrates how a single tower turns nowhere into a definable, albeit unseen social locus. It also taps into the enduring and peculiar rapport between technological omnipresence and vacancy. The Enola Gay slumbered in a Leftover Field hangar because the military considered the place so secluded, a good place to keep a secret that would shape the ensuing century. Stratman’s work similarly intimates that the infrastructure which exerts such an impact upon built spaces and cultures might just surge and vibrate in areas overlooked as voids.

Yet participating with this barbershop-colored transmitter is as fleeting as the Morse Code which tells us that an RKO picture is about to start. The wind picks up, the sun falls, the Center closes, and the tower continues standing although its audience has departed. With mouthfuls of studded grit accompanying visitors to their cars, there is the sudden recollection of a radio broadcast in W.G. Sebald’s Austerlitz (2001), where “the voices moving through the air after the onset of darkness, only a few of which we could catch, had a life of their own, like bats, and shunned the light of day.”10 The same could be said for these countless towers, hovering in between countries, laws, landmarks, developments and memories; or buried in plain sight, awaiting excavation; their beacons ringing against the cerulean dome of night, slowly breaking down under the elements.

Thanks to Clara Robinson for her invaluable aid and commentary upon this essay.

Image Credits:

1. The RKO Logo + Author drawing + photograph

2. NORAD Structural Support + Groundbreaking Ceremony (1960s)

3. Nikola Tesla Near His Electric Amplifier

4. László Moholy Nagy’s Radio Tower Berlin (1928)

5. From top: Guy Maddin’s Brand Upon the Brain! (2007) + Edward Hopper’s Ground Swell, 1939. Oil, 361/2 x 501/4 in. Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Museum Purchase, William A. Clark Fund

6. From top left: Observando el Cielo Poster and Image + Sutro Tower in San Francisco

7. Verizon’s “Rule the Air” Logo

8. Deborah Stratman, Power/Exchange (photo courtesy Amanda Steggel, 2008)

Please feel free to comment.

- See, see now the fabulous home of the Nevada Lightning Lab, run by the great Greg Leyh. [↩]

- The RKO logo was subsequently resurrected in the 1980s and ‘90s as a computer-generated derivative with the strangest lightning bolt imaginable, and font that resembles the typeface for no less than a Whitesnake album. See Rick Mitchell, “Everything You Wanted To Know About American Film Company Logos But Were Afraid To Ask,” Hollywood Lost and Found,

http://www.hollywoodlostandfound.net/stories/studiologos/page4.html (accessed 6/19/11). [↩] - Anna McCarthy, Ambient Television: Visual Culture and Public Space (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2001), 14.

Alexander Russo imports McCarthy’s theory of televisual broadcasting in lived spaces for radio. See Russo, Points on the Dial: radio, space, attention (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2010). [↩] - Alexander Nemerov, “Ground Swell: Edward Hopper in 1939” American Art, Vol. 22, No. 3 (Fall 2008): 58-67. [↩]

- Michael Sicinski describes Observando el Cielo in a similar fashion: “…it implicitly turns the sky not into the domain of deities, but into the cluttered highway of waves and signals, air and space travel, a tableau of human endeavor against a celestial backdrop with its own, radically different temporal agenda.” See Sicinski, “2007 New York Film Festival’s Views from the Avant-Garde sidebar,” http://academichack.net/Views2007.htm (accessed 5/23/11). [↩]

- Such figures have little relation to the scheming, centralized conductor of Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds (1938), which reinforced fears of radio as a tool of audience control and homogeneity. Nor do they entirely jibe with the historical account provided by Susan Douglas in Listening In (2004) of a tightly interwoven, communicative network of young radio enthusiasts. Rather, numerous fictional disc jockeys both urban and rural, including those in The Outer Limits, Vanishing Point (1970), The King of Marvin Gardens (1972), The Fog (1980), and The Night Listener (2006), are painted in solitary strokes. Equally common are forlorn listeners, key among them the castaway characters of Kobo Abe’s Woman in the Dunes (1964) or Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay (2000).

In less fantastic dimensions, one cannot overlook installation artist Mary Lucier’s following recollection, “Virtually Real,” in Millenium Film Journal‘s Spring 1995 issue:

“There was one piece of electronic magic in my life, however, which made an indelible impression, and that was an enormous Magnavox console, consisting of a 78rpm turntable enclosed in the upper left hand cabinet, and a radioactive-green radio dial on the right side, with AM, FM (which required a special antenna that we did not have), and, my favorite, Short Wave. Underneath all this in the console, at a perfect height for a ten to fourteen year old girl seated in rapt attention four inches from the cloth grill, were the most magnificent loudspeakers I’d ever heard […] I’d sit up late at night, long after everyone else had gone to bed, with both hands and eyes on that luminescent radio dial and my body pressed close to those fabulous loudspeakers, scanning the dial nonstop until I could recognize Hank Ballard and the Midnighters or Ray Charles or Fats Domino or Etta James or Laverne Baker or Elvis, by just a few bars, via stations that came in only at night, illuminating a landscape from Nashville to Cleveland to Detroit and beyond.

But the real thrill was listening to Short Wave. The staticky squawks and rhythmic bleeps, punctuated by fragmentary bursts of mysterious speech, made up another, more bizarre landscape that I fantasized as space and time travel. Hunkered down there against that machine for hours on end, cross-legged on one of my mother’s somewhat threadbare Oriental rugs, I experienced a deep crisis of faith. In the same spirit with which I used to pray intently to God, or at least Jesus, “Please, oh please appear to me or give me a sign,” to make Himself known so that I could partake of a transformative miracle, become a believer, and leave behind, once and for all, my deeply ingrained agnosticism and my dreary small town life, I tried to will that carpet to fly.”

One must also remember the case of John Wells, a fashion photographer turned desert Thoreau residing in the West Texas “moonscape,” who annually pledges $500 a year to Marfa public radio – “his lifeline.” See http://thefieldlab.blogspot.com/ [↩]

- Kirk Harnack, “Tower maintenance,” Radio Magazine Online, September 1, 2000, http://radiomagonline.com/transmission/towers/radio_tower_maintenance_2/ (accessed 6/2/11).

John Battison, “Tower inspection and climbing,” Radio Magazine Online, July 1, 2006

http://radiomagonline.com/transmission/radio_tower_inspection_climbing (accessed 6/15/11). [↩] - Kevin McNamara, “A DIY Approach to Site Security,” Radio Magazine Online, June 1, 2011

http://radiomagonline.com/transmission/towers/diy_site_security_0611/index1.html (accessed 6/15/11). [↩] - The Lay of the Land: The Center for Land Use Interpretation Newsletter, Winter 2003, 4. [↩]

- Winifred Georg Sebald, Austerlitz, (New York: Modern Library, 2001) 164-166. [↩]

This is a pretty interesting piece, Paul, and really well written. Thanks for the read. Your work reminds me of a lot of other writers; mainly, have you read anything by Asma Naeem? She’s doing a dissertation on the imagery of listening in American art, from the Ashcan school to Edward Hopper and more. Also has a piece out called the “Aural Imagination.”

Always glad to see someone writing about the RKO tower ;) Thanks!

I enjoyed reading this, and by and large, I buy the idea that radio towers “remain undomesticated, daunting in their complexity, size, and military or corporate ownership, things not readily recycled.” There are definitely many artists (not to mention filmmakers, TV shows, etc.) out there who have incorporated radios into a wide variety of scenes that also deal with family and domesticity (remember, radios became furniture pretty early on) but, like you said, can’t think of many others who incorporate the actual towers, excepting photographers, maybe. Have you looked at Lisa Parks’ arts of ionospheric exchange piece? Might be an interesting followup.

As others have said, I enjoyed this piece, and it is pretty sharply executed. However, I’m wondering if you can go a little further on the *many* artists that have re-appropriated radios in their work. And where exactly is the radio in the Hopper painting? Not sure I see the connection.

Thanks,

Shane.

Saw Observando el Cielo at NYFF a few years ago and was absolutely blown away; can’t believe I came across it again on Flow. Nice surprise. Wish I could get a copy. You give it a really different context I don’t remember having at all when I saw it – it’s so celestial, and I seem to be able to recall the images much more than the soundtrack, unfortunately – but like you say, it also has a major technological referent as well which is worth paying attention to.

Thanks for sharing!

A beautifully written piece, with a lovely lyrical coda! More academic writing should be this wide-ranging and heartfelt. Wish I could take a road trip to Stratman’s steeple…