The Children of Chuck Barris: Reality TV in the 1970s

R. Colin Tait / FLOW Staff

I used to be with it, but then they changed what ‘it’ was. Now, what I’m with isn’t it, and what’s ‘it’ seems weird and scary.

Why the fax machine is nothing but a waffle iron with a phone attached.

— “Grampa” Abe Simpson

Television, and by proxy, writing about television tends to favor the current, the new and the quality, oftentimes at the expense of thinking seriously about the old. Flow is no exception to this rule, as the journal was borne of the pressing need to address TV and media texts as they occur, as well as speaking to the highly-accelerated rate of shows as they debut, make their mark and often disappear in the time it takes to write about them. At the same time, TV audiences tend to skew on the older side, resulting in a divided perception between ideas of what purpose television serves today. This includes the age-old debate between high and low and between entertainment vs. enlightenment, resulting in a schism which is reflected in the deep division in programming, between the extremely cheap model of unscripted and the higher-end, boutique offerings of cable.

In the meantime, concepts like the “Big Three” networks seem increasingly to belong to the last century, urging that we revisit and reexamine the myriad texts, operations and shows of the past, and the 1970s in particular. At the risk of sounding like Grampa Simpson, figuring out what TV is means revisiting what TV was, examining the shows that are slowly receding from memory at the expense of letting the brand new wait a little while. Two shows demand our attention, particularly as they signal the roots of our contemporary media landscape, and Reality TV in particular — The Gong Show and Battle of the Network Stars. Along the way we should recall that what contemporary shows still trade in is the spontaneous and liveness – which is the essence of the medium – as well as the pleasures inherent in watching someone make an ass of themselves.

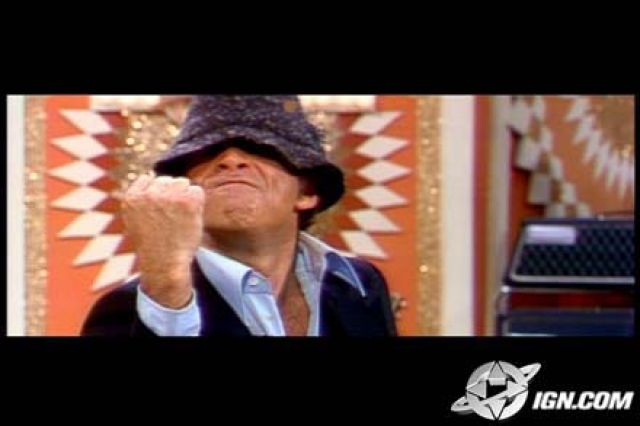

We can see the roots of almost every contemporary Reality TV show gig in each of these shows, including familiar challenges, smarmy hosting, extroverted contestants, B-, C- and D- level stardom, as well as our inherent desires to watch something terrible, rather than something good. Chuck Barris remains one of the people most responsible for the current state of today’s television. As Lisa W. Kelly astutely observes in a recent Flow article, “And the Winner of Britain’s Got Talent is…” this show and its American counterpart have Barris’ fingerprints all over it. Aside from its slick production values, America’s Got Talent, its three-judge panel (who use x’s instead of a huge gong to tell contestants that they are no good), is virtually indistinguishable from its seventies counterpart, save, of course, for the presence of a smiling and dancing Barris.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ACpNVD5GMUw&feature=grec_index[/youtube]

While Jerry Seinfeld may have lent the whiff of his celebrity to his producing NBC’s The Marriage Ref, this show borrows – if not steals outright – the format of Barris’s The Newlywed Game. We need not delve too deeply into this comparison to see the roots of The Bachelor or any other contemporary dating shows landing in Barris’s lap, except to say that the contestants of this “dating game” are chaperoned in their exotic locales by the crew of camera people and producers, loaded with alcohol and encouraged to misbehave. Finally, we see the fusion of the good and the bad, the privileging of the average “joe” rather than the star, as well as TVs tendency to make people look bad as the payment for entertaining us. Though it seems as though the task of finding, seeking and displaying talent is the raison d’etre of each of these shows, everybody knows that they are actually about the opposite — showing us the worst and the least talented acts for our various pleasures, as well as encouraging an endless supply of “talent” to humiliate themselves, to work for nothing besides the measly excuse to be seen on TV, and the opportunity to be seen by millions.

While Barris was decried as everything negative under the sun in his heyday, including the “Ayatollah of Trash,” to the “Godfather of Reality TV” and is mostly remembered as the playful host and creator of The Gong Show, Barris was actually much more than that, including one of the most prolific TV producers of his era. Not only did he create the formats of some of the most popular game shows of their day, including the Dating and Newlywed Games, but he discovered something much more important — that people wanted to be spontaneous and silly on television, and that they wanted to be on television no matter what. More to the point, he discovered the pleasures of watching everyday people let down their hair and be extroverts, and our pleasures in watching them do so.

In a recent interview for the Archive of American Television, Barris states that he saw his biggest contribution to television in the late 1960s was the reintroduction of spontaneity and liveness to the medium, at a time when every game show, soap, newscast and series was scripted. In this vein, I would offer that Barris, yes, the Chuck Barris is as important a figure to the history and theorization of the medium as Marshall McLuhan, as so recently observed by Charles Acland and a rash of articles devoted to McLuhan’s legacy. We should also recall that Barris claims that he originally wanted The Gong Show to be a legitimate talent contest, but that he couldn’t find enough good acts to comprise an entire show.

My love of television is borne of this moment, inseparable with what is now considered the “bad object.” My heroes as a child were not only Barris, the Unknown Comic and Gene Gene the Dancing Machine, as well as the rash of B-, C- and D- level “celebrities” who frequented these shows as contestants and hosts, but also the stars who stepped out of their scripted moulds and let their outsized personalities exceed the boundaries of their famous characters.

Speaking of whom, we should remember that the earliest Reality TV stars were also the scripted TV stars as well. The Battle of the Network Stars, a relic of the “Big Three” network era, is not only the quintessential model for our contemporary “star” branded mediascape (Dancing With the Stars, Circus of the Stars, Skating with the Stars, Celebrity Apprentice), but is virtually the model for every Survivor, or reality show challenge, complete with babes in bathing suits, and oh-so-serious competitors. That the “stars” on the show were competing for the grand prize of the very low sum of $20 thousand a piece, in addition to representing the networks with the free publicity of their appearances, should remind us of the eternal cheapness of Reality TV, and that the exploitative nature of the medium extends to any and all talent pools.

I want to end on this point, offering a few final provocations. Though the state of Reality TV is much decried in our contemporary era, revisiting these early texts as well as investigating the pleasures of watching them offers a necessary corrective to a field that sometimes seems entirely devoted to the new, at least in its online form of criticism. At the same time, we should understand (as studies like Derek Kompare’s Rerun Nation suggest) that television is a medium hell-bent on cheap production, and this also means recycling, rebooting and ripping-off old ideas as well. In other words, like Grampa Simpson’s quote that begins this essay, sometimes this means looking TV programming straight in the face and declaring that it skews to the bad rather than the good, and that sometimes a new show is merely a “telephone with a waffle iron attached,” rather than something worthy of our immediate attention.

Image Credits:

1. Grampa Simpson from FOX’s The Simpsons Answers the Iron

2. Chuck Barris on The Gong Show

Please feel free to comment.

There was a moral as well as an aesthetic hierarchy in The Gong Show. Contestants who were “innocent” or “sincere” were given nicer treatment than people who should have known better about their lack of talent. People who were self-aware of how bad their talent was got the best ride: the panelists and Barris played along and “enjoyed” them. That element seems missing from current talent contest shows (though I could be wrong, don’t watch them).

I can’t understand why you didn’t mention Barriss work with the CIA. ;-)

Chuck Kleinhans

Fascinating and thought-provoking piece. One of the problems in discussing banality is that the term easily crosses over as a term of reference from the object or style of representation (in particular the unnoticed background to everyday life – as you say, the telephone poles we don’t notice) to the nature of viewers’ relationship to the images themselves.