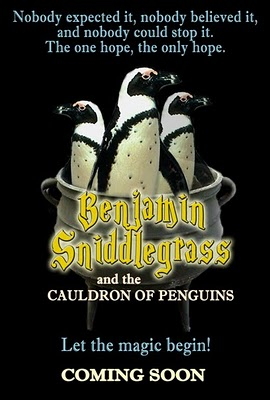

The Curious Case of Benjamin Sniddlegrass and the Cauldron of Penguins

Tama Leaver / Curtin University

While the fact that a film with the name Benjamin Sniddlegrass and the Cauldron of Penguins exists at all is a surprise, the awkward title pales in comparison to the incredibly unlikely tale of how the film came to be. To contextualise Benjamin Sniddlegrass, first it is important to know a little more about Kermode and Mayo’s Film Review, a popular BBC radio show hosted by radio presenter Simon Mayo and well-known British film critic Mark Kermode. Their radio show, affectionately nicknamed ‘wittertainment’ by the hosts and a large and loyal listenership alike, airs Friday afternoons on BBC Radio Five Live and, like many radio shows, has embraced various online forms of interaction with listeners. While only aired in the UK, each show also has a live video stream and is widely distributed across the world as a weekly podcast. Mark Kermode has a related ‘Kermode Uncut’ blog, both presenters interact with viewers on Twitter, and in each episode the hosts engage with a plethora of comments from listeners (which are either submitted during the show, or in the days preceding the broadcast). As a notable example, towards the end of last year Kermode and Mayo solicited listeners’ opinions on the worst things other people do during film screenings, which became the basis for the Wittertainment Code of Conduct, a tongue-in-cheek series of ten cardinal rules of behaviour to which all good cinema viewers should adhere.

In one podcast, which included a less than flattering review of Percy Jackson and the Lightning Thief (2010), Kermode lamented how derivative it was of the Harry Potter franchise, which is especially ironic given the director of Percy Jackson, Chris Columbus, also helmed the first two Potter films. At one point, Kermode made a throw-away comment that, given the similarities, the film may as well have been called ‘Benjamin Sniddlegrass and the Cauldron of Penguins’.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hbzoOxgzYt4[/youtube]

While that throw-away ‘Benjamin Sniddlegrass’ line would normally have simply been forgotten in a week or two, the oddity of it appealed to listeners who were intrigued. For a couple of listeners at least the notion of Benjamin Sniddlegrass was so amusing that they actually created mock film posters touting the future release of the imagined film. However, for one Wittertainment fan, even creating posters wasn’t enough, and thus on the other side of the world, Sydney resident Jeremy Dylan embarked on a mission to transform Kermode’s off the cuff comment into a fully realized feature film.

Drawing on many friends and favors, Dylan managed to write, direct and assemble a cast and crew who’ve contributed to a 70 minute film with a total budget of just $9,000 Australian dollars. Benjamin Sniddlegrass and the Cauldron of Penguins, or BSATCOP as it has become known, was shot on location in Australia using what Dylan calls guerrilla film-making (which means, amongst other things, all the filming was done without permits or payments). The film itself certainly doesn’t aim for a mainstream audience; the deliberately derivative magical boy’s coming-of-age plot serves more as a vehicle to join together various Wittertainment in-jokes rather than to achieve more than a semblance of narrative coherence (which in and of itself is something of an in-joke since one of Kermode’s oft-quoted lines is that particularly bad films hail the “death of narrative cinema”). BATSCOP prominently features Skiffle music due to the fact that when not reviewing films, Kermode is part of a Skiffle band, it features enigmatic director Werner Herzog as a character (the real Herzog was infamously shot with an air rifle, but unhurt, during a 2006 interview with Kermode), and the central villain, Lord Emmerich, is named for director Roland Emmerich whose doomsday film 2012 (2009) received a particularly scathing review on Mayo and Kermode’s show.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HNKyce-QAps[/youtube]

In this sea of in-jokes, perhaps the most surprising thing is to hear the voice of a very familiar narrator: Stephen Fry. Now, Fry is a long-established fan of Kermode and Mayo (for a long time he was on the list of people that the duo had to mention in every single show) but when Jeremy Dylan thrust an envelope containing a script and plea to contact him into Fry’s hand after a comedy show at the Sydney Opera House last August, even Dylan was shocked when Fry emailed saying he could spare 30 minutes. Dylan turned up shortly thereafter with his audio equipment and in little more than one take, Stephen Fry’s voice became the most recognisable part of the BSATCOP experience.

There are plenty of ways that BSATCOP might be understood or framed in a scholarly context. It would be easy to build on Henry Jenkins’ work in Textual Poachers (Jenkins, 1992) and examine the power of shared fan culture which led to Dylan’s interest, Fry’s participation, and the attention of Wittertainment listeners across the globe.1 The unlikely film could be examined via Chuck Tryon’s work in Reinventing Cinema (Tryon, 2009), situating BSATCOP as an example of the lowering barriers of participation, production, distribution and cost, placing it alongside earlier exemplars such as The Blair Witch Project (1999).2 Similarly, the ability of Dylan to engage in this project in Australia, on the basis of an intriguing comment in a UK radio show, could certainly be examined via Axel Bruns’ notion of produsage (Bruns, 2008), focusing on the collapsing boundaries between producers and users.3 However, given the genuinely odd nature of this film, it is also possible to simply pause for a moment and appreciate the bizarre flows which saw a UK radio show inspire an Australia fan to make a full-length film, premiere it in Australia, and then distribute it globally as a digital download.

Of course, to fully appreciate the oddity of BSATCOP actually existing, it’s well worth seeing the moment where the Ouroboros finally starts to eat its own tail. Enter the moment in which Mark Kermode and Simon Mayo review the film that grew from their single throw-away comment a year earlier:

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nSsKlxnER8c[/youtube]

Image Credits:

1. Benjamin Sniddlegrass and the Cauldron of Penguins Poster

Please feel free to comment.

About time someone took a more scholarly look at our little project. I guess I’ve got some reading to catch up on from Jenkins, Tryon and Bruns.

It may be worth noting that the film is also available as a Special Edition DVD.

Thanks for the article, Mr. Leaver.

Another interesting and well-researched post, Tama. I wasn’t aware of the Sniddlegrass phenomenon until reading this column and I really enjoyed your incorporation of media theory from scholars like Jenkins to explain the power of fan culture in this instance. Now I guess we all need to get our hands on that Special Edition DVD!

To add another wrinkle, BSATCOP is now available as an expurgated Producer’s Cut, viewable for free at benjaminsniddlegrass.com and http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eaFsgYvhi8Y.

Je suis tout à fait d accord avec cette opinion. Je dois dire que je ne regrette en rien de m’être abonné à votre weblog. Amicalement,

consultant seo salaire http://meilleurpandagooglewikipedia.wordpress.com formation référencement