Time Wasted

Ernest Mathijs / The University of British Columbia

If film cultism today is only what William Bainbridge and Rodney Stark1 would call an ‘audience cult’ or ‘client cult’, and what Janet Staiger calls ‘visible fandom’ 2, if cult cinema’s current impulse is disconnected from the history of cultism, why do cult receptions of television and cinema not lose all of their appeal as a factor of resistance against the mainstreaming of culture?

Well, for one thing, there’s time. The previous two columns I posted here – on cultist uses of media during Halloween and the Yuletide season have attempted to single out specific viewing times as crucial to the kinds of experiences they are. And these are just two examples. This connection between idiosyncratic approaches to time-spending and cult run through the history of film, television and audiovisual media.3

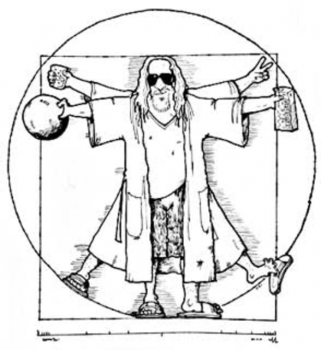

It is the concluding suggestion of my three columns – and at this point it is really only a suggestion begging for more research, hence my trying it out on this platform – that (by and large), the cult viewing experience is still relevant because films and shows are turned into cults by viewers who refuse, or cannot afford to use the ruling models of the progress, conduct and governance of spending time with media; viewers who consume too much, not enough, or inappropriately when measured against the clock; viewers stuck watching horror films at Halloween, melodrama and musicals on television during Christmas, and watching Casablanca for Valentine’s Day; nothing original, nothing new, nothing distinguished, unproductive and not really classy. But, at the same time, free enough to do just that, and again and again. In his essay on Casablanca, Umberto Eco sees audience participation, especially their reciting of dialogue, as an example of how films that are turned into cults require the viewer to “break, dislocate, unhinge it so that one can remember only parts of it, irrespective of their original relationship with the whole”4. That means breaking out of time’s progress as well. Contemporary illustrations would be The Big Lebowski’s ‘dude’ or Ginger Snaps’ ‘goth girls’ – the dudes and goth girls from the movies as well as those in their audience.

Eco’s remark is one of numerous similar ones found in literature on cult cinema, cult television, and cultist uses of the internet, which imply that media cultism has no use-value, no exchange-value, perhaps not even a Baudrillardian sign-value but only what Walter Benjamin via Karl Marx would call a fetish-value – a form of surplus immeasurable via tools designed to track the functional and proper ‘spending’ of time.

I am honestly unsure if this observation is – or should be – anything more than just a coincidence or if it relates to a deeper mechanism of how cultism retains a form of resistance against the relentless commodification of leisure time, or even more, a rebellion against the usage of time as an economic form of measurement at all. I’d love to believe such a relationship exists, and that it could be connected with philosophical approaches on the management of time.

Here is why I would love to believe this. One main implication of all the modes, tools and instances of media cultism, and indeed the purpose of the epiphanies cults chase, is the subversion of a steady progression of time. There have been many discussions, ranging from Stephen Kern’s historical study of the culture of time and space, over Henri Bergson’s, Gilles Deleuze’s and Eric Alliez’ philosophical discussions of the representation of the passing of time, to John Zerzan’s anarchist assaults on the construction of time that link films to questions on how the governance of time is a convention intended to support certain worldviews5 Cult media receptions are a reprieve from that convention by suggesting, through their own claims about how time works, that there is ‘another time’ (to quote the opening of Streets of Fire).

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oJGo2rvfSuA[/youtube]

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5vWXS5nHdk4[/youtube]

I have mentioned elsewhere – during heated discussions about the relevance of cult cinema today where convictions can take over research findings (see CINEASTE for my role in this particular discussion) that cult films present discontinuities, repetition, time travel, or fragmented time – cult films are known for having their timing ‘off’, and watching them repeatedly is literally taking time off. The modes of the cult viewing experience turn this ‘off-time’ into a form of resistance against exhausted impositions of progress and a compartmentalization of time into “working hours,” “shifts,” or “deadlines”—culminating in “just in time” or “around the clock” economies. The discombobulated ‘future where you and I will spend the rest of our lives’ of Plan 9 From Outer Space, the eternally ‘forgotten and lost’ times of The Lord of the Rings, the perpetual ‘Tuesdays or Thursdays or any day for that matter’ of The Gods Must be Crazy, the ‘after hours’ of After Hours, the ‘time warp’ of ‘midnight movie’ The Rocky Horror Picture Show, the ‘killing of time’ of the continuous reception of Donnie Darko, the repetition of the Christmas Holidays – and Christmas Holidays’ viewing – of It’s a Wonderful Life, the numerous ploys around messed-up timing in Casablanca (“What watch? Ten watch. Such much?” – or the ‘romantic interlude’ signaling the passing of time when Ilsa and Rick spend the night together6, all suggest a refusal to adhere to demands for efficiency.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Th0G8rkhBqg[/youtube]

At the very least, they offer a suspension of ‘proper’ time for the duration, and hopefully a little beyond that, of a film’s screening length. Beyond that, repetitively celebrating a cinema whose misuse or abuse of ‘time proper’ exists through the inappropriate conduct of time in its reception can develop into an attitude of cultural rebellion. This can happen by breaking the conventions of the governance of time in film reception (watching films too often, and at other times than prescribed7), by not letting the screen time run its course (using the remote to speed up, slow down, or endlessly repeat and pausing8), or by making allowance for boredom and idling as positive viewing experiences – deliberately wasteful experiences, a waste while being wasted. It is in such uses that much of the reputation of cult cinema as cool and maudit is enveloped. Cult film celebrations pretend to challenge the continuity of time and, through that, at least give the impression they contest dominant ideology, rejecting the idea that things only get better, or refusing to believe steady progress is the only path.

I would like to see us link this reputation of cult cinema to the reputations of the groups of people it is said to attract, to the classifications of ‘class’ with whom cult receptions are said to share sociological, ideological, aesthetic and rhetorical links: vagabonds, tramps, squatters, bums, hobos, troupes, bohemians, anarchists, fellow travelers, Zapatistas, gangs, hooligans, mobs, crowds, masses, youths, cats, beatniks, rockers, mods, hippies, ramblers, ragamuffins, nomads, wanderers, renegades, outsiders, fanatics, weirdos, witches, queers, misfits, nitwits, meatheads, scum, punks, rastas, addicts, dropouts, losers, idlers, dazers, dolers, slackers, couch potatoes, slouchers, strollers, flaneurs, … what Kinkade and Katovich call, in relation to The Wizard of Oz and Freaks, the “little people’9 How would analyses of the spending of time stand up here?

Even if such links turn out to be casual and accidental, even if they would just be markers on a hub in the scale-free network of media cultism, which I do not believe they would be limited to, even then they would still inform a bond between types of viewers and films championing inefficiency, loss, waste, failure, and marginality, both attempting to “fritter and waste the hours in an off-hand way” to cite Pink Floyd’s song ‘Time’.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MYiahoYfPGk[/youtube]

It is in this sense that Andrew Ross’ observation that camp film relates to ‘surplus’ labor becomes most relevant10. From the perspective of the cultist viewer, it is a surplus labor that creates a cultural niche in which the refusal or inability to be productive, to have one’s labor (the labor of love, watching movies) ascribed a use, exchange or sign value, becomes something audience and film share –against the ruling times. And what better way to ‘perform’ this than through films that invite us to “have the time of our life”?

Subverting the sequencing of time and the steadiness of progress into ‘cosmic time’ (to use Eric Alliez’s term11) was certainly an aim of the original Dionysus cult, and of many cults since. The fact that violence and sex were among the means to achieve the abandon that would accomplish this accounts for a main reason why the term cult has been dismissed from cultural discourses so vigorously. In the form of the reception of films (often violent or sexually charged films), television shows such as Lost, Star Trek, or Robin Hood (all of which question time), and via ritual experiences that have sublimated shadow-representations of time-travel, cult has gradually made a re-entry into accepted culture.

Only in a few guises would any culture condone the myriad of ritual activities around the challenge of time without sanction. Film and television cultism is one of them. That might be exactly why cult media experiences are so appealing, and why they can continue to imply that they contain an epiphany or gasp that preempts, precedes and even precludes, ‘history’, ‘knowledge’ or ‘consciousness’. It is also why specific research into cult cinema receptions remains relevant –and if my suggestion is ever going to get mileage such research is indeed urgently needed. As any cultist knows who hears Ingrid Bergman say “play it once” in Casablanca: she means ‘play it again’. Once is again.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wo2Lof_5dy4[/youtube]

Image Credits:

1. Cassablanca and the Cult of St. Valentine’s Day

Please feel free to comment.

- Cowan, Douglas & David Bromley (2008), Cults and New Religions, Boston: Blackwell, 89. [↩]

- Staiger, Janet (2005), Media Reception Studies, New York: New York University Press, 125. [↩]

- To name what might well be the best known example, the significance of the specific time of Valentine’s Day for the cult of Casablanca – at the Brattle Theatre that started its cult or as far afield as Scotland where the a romantic pairing of the film and dinner costs only 29 pounds per person. [↩]

- Eco 1986: 198 [↩]

- Kern, Stephen (1983), The Culture of Time and Space, Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press; Deleuze Gilles (1983), L’image-mouvement: Cinema 1, Paris: Editions de Minuit; Deleuze, Gilles (1985), L’image-temps: Cinema 2, Paris: Editions de minuit; Alliez Eric (1996), Capital Times: Tales from the Conquest of Time, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; Zerzan, John 1994), ‘Time and its Discontents’, in Running on Emptiness: the Pathology of Civilization, Los Angeles: Feral House, 17-41; Donato Totaro (2001):’ Time, Bergson, and the Cinematographical Mechanism’, Offscreen, http://www.horschamp.qc.ca/new_offscreen/Bergson_film.html [↩]

- For an elaboration on this scene, see Maltby, Richard (1996), ‘A Brief Romantic Interlude: Dick and Jane go to 3 ½ Seconds of the Classical Hollywood Cinema’: in David Bordwell and Noel Carroll (eds), Post-Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies, Madison (WI): University of Wisconsin Press, 419-433.

[↩] - This also means ‘other times than midnight’ whenever midnight screenings are being incorporated into mainstream release (and thus time management) patterns [↩]

- Consider, in this respect, this telling critical comment on the status of Scanners as a VCR cult movie (Cronenberg, 1981): “watermelon left in a microwave: the kind of scene where you go ‘yuck!’ and then play it over, in slow motion, about six times” (Pevere Geoff & Greig Dymond (1996), Mondo Canuck, Scarborough (ON): Prentice Hall, 39). [↩]

- Kinkade, Patrick & Michael A. Katovich (1992), ‘Toward a Sociology of Cult Films: Reading Rocky Horror’, Sociological Quarterly, 33 (2), 197. [↩]

- Ross, Andrew (1989), No Respect; Intellectuals and Popular Culture, London: Routledge. [↩]

- Alliez Eric (1996), Capital Times: Tales from the Conquest of Time, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [↩]

When I first read your argument that cult films present “discontinuities, repetition, time travel, or fragmented time” I thought that this could not possibly be true for all of them. But once I started to analyze the narrative patterns of films like “Casablanca” and “It’s a Wonderful Life,” I quickly realized that this really is the case. While both films break Hollywood’s classically linear narrative structure through Rick’s mental time travel back to Paris in “Casablanca” and the fragmented structure of “It’s a Wonderful Life’s” flashback to George’s childhood and flashforward to what life would be like without him, both films also contain repetitious lines of dialogue like “Here’s looking at you, kid” and “Every time a bell rings an angel gets his wings” in addition to sounds that can be heard throughout the films like “As Times Goes By” and bells ringing in “Casablanca” and “It’s a Wonderful Life,” respectively. Perhaps this is part of the reason why these classics turn into cult films–the repetition in the films carry over into the repetition of watching them and eventually turns into a ritual, which is a form of repetition within itself.

An interesting question was raised when you asked why the fact that these films turned into rituals did not cause them to loose their appeal as a “factor of resistance against the mainstreaming of culture.” I suppose that by being turned into a ritual these films do by default become mainstream, but that does not necessarily mean that they lose their resistant elements. In fact, both of these films in their own right are resistant/rebellious by nature. “Casablanca” is a film that is all about going against the grain and fighting for the underdog. It also centers on numerous rebels: Rick, Ilsa, Victor, and even Ugarte, who are all characters audiences fall in love with time and time again. At the time the film was released, this resistant theme to the film would have been something appealing to audiences, and it is something that no matter the time, audiences could relate to whether it be 1942 or 2010. On a different note, when “It’s a Wonderful Life” was released, the films struggle with contemplation of suicide and the subversion of Jimmy Stewart’s persona was resistant to the other films that were being released in 1946. Both of these films stand for something outside of themselves, which everyone can relate to, and it seems to be why they have turned into the cultist artifacts that they have become. Even so they have become maybe washed out since they have been viewed so many times, especially around Valentine’s Day and Christmas, yet I still feel that does not take away from their resistant nature.

I feel that these economically-coded notions of time are very modern perversions. Even in the middle ages, when most people were peasants who ‘belonged’ to the land – your existence on earth was given meaning by the role you played in the sustenance of your community, through a concrete, practical contribution to the store of food and necessary goods – there was a coequal belief that some part of you belonged to a greater reality completely outside of these mechanical necessities of existence. Your time was due, in so much as it was needed for the functioning of society; to allow the group to live. But this social responsibility was something to be discharged without either pride or shame. The real business of living was a personal one.

Even in the age of the robber barons, places like Central Park in New York were thought to be the *right* of working men and their families: our time on the assembly line was no more the ‘reason for our being,’ than our time with the hoe and scythe had been. It was necessary to put food on the table. The *reasons* for our lives were to be found in family and in self. The betterment of self may be constructed as ‘spending time wisely,’ on high-cultural artifacts, but the idea that such time *must* be *earned* by our previous labors, rather than being *due* us by natural right (or a divine duty to ourselves, in a world greater than physical labor and necessity) is a depressing notion.

“Casablanca” is about a man who works hard, has achieved success, a certain amount of influence with the powers-that-be, and the physical and economic security that these things entail. It is also about how these achievements are *false* achievements, and ‘don’t amount to a hill of beans’ in a world where more is at stake than these things. I don’t think we can take Rick’s actions as the abnegation of the self or the responsibility to one’s self: I would argue that the real message of a film like “Casablanca,” or “It’s a Wonderful Life,” is not about being content to endure the loss of love for the greater good, or (in the latter’s case) a lowering of professional and personal expectations. Rather, Rick’s superficially (economically) successful life in Morocco (or George Bailey’s longing for travel and a high-status job) is presented as the ‘time out,’ something which has sucked the meaning out of his existence.

In these ‘ritual’ films, pursuit of these worldly goals is presented as a denial of the self’s need for meaning, rather than its fulfillment through economic means. Such means are seen, precisely, as being *toxic* to real success as a human being. In “Casablanca,” Rick does not forgo happiness with the woman he loves for the greater good; rather, he forgoes the economical for what will give his life meaning and humanistic purpose. These qualities of rebellion against commodified markers of success and wealth mark many of the ‘cult’ figures of pop culture in the last sixty years or so. They deny that our time is a bauble already owned by our bosses, but say that rather it is a place within which we can most valuably construct our own narratives of what is meaningful to us. We do this, either through contemplation of Olmsted’s urban landscaping, Curtiz’ fairy tale of romantic heroism or Capra’s classic film, by making use of our time to *feel* something richer and more deeply meaningful than the rumbling of the factory line, and company time.

Adorno has a great essay called “Free Time.” You might want to check it out.

thanks so much for these fascinating comments. I agree fully with Cary’s historical elaboration. In fact, when I started work on this topic, it was part of a larger study of ‘rebellions against ‘time”. I felt inspired by Stephen Kern’s book ‘The Culture of Time and Space’, which looks into developments in the arts (film chiefly amongst them), literature, technology and science between the end of the 19th C and the outbreak of WWI. Kern’s argument is that accelerations in the experience of time (I believe he calls it the beginning of the collapsing of the concepts of past and future into the present – the past as something working through in the present is a particularly important element for film analysis based on Freud) coincide with commodifications of the usage of time, in professional as well as private life experiences (i.e. ‘spending time’). Henri Bergson is a huge point of reference for Kern. But when I looked at how more recent theories of film had used Bergson (i.e. Deleuze), I became frustrated with how film was narrowed down to ‘good cinema’. I felt Deleuze and the Deleuzians missed out on the chance to include ‘bad’ cinema and ‘cult cinema’ in discussions of the ‘time image’. In films such as Plan 9 From Outer Space, The Room, and many many others the naive (or not so naive) errors of continuity disrupt the ‘normal’ flow of cinematic time so profoundly that they irk viewers. But instead of working as a form of enlightenment or enrichment (which is what I believe Deleuze etc lead to), there seems to be no redemption in the form of a function for these films – they are ‘only’ cult films.

There is much more work to be done on this topic, and I believe the comments above show some way towards how this can be accomplished. But the connection between representations of time in cult cinema (and its receptions) and experiences of how we perceive issues of power in culture is – I think – essential to the discussion.

Alex: thanks for the reference. I will certainly check this out.